Photograph provided by Madero, Michoacán residents.

“In Michoacán right now I think the most sensitive, serious environmental issue is the indiscriminate change of land use for avocado crops … [which] puts at increasing risk our biodiversity, the provision of water, and the forests in this state.” – Michoacán’s Secretary of Environment Alejandro Méndez.1“Avocado: Business, Ecocide and Crime: Part 1,” (Aguacate: negocio, ecocidio y crimen: Parte 1), UGTV Territory Reporting, Sept. 7, 2022, video clip, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PaaaJXAx6NQ (accessed September 12, 2023).

“Notwithstanding our constant refusal to sell some fractions or the totality of the land of our property… more than 59 hectares have already been invaded and deforested.” – Letter from Jalisco family to U.S. Trade Representative and U.S. Ambassador to Mexico.2Letter from Jalisco family to Ken Salazar, U.S. Ambassador to Mexico and Katherine Tai, U.S. Trade Representative, September 13, 2021 (translated by U.S. government), obtained via FOIA request from USTR.

“If you point the finger or talk, they’ll kill you.” – Indigenous community leader from Michoacán.3CRI interview with Indigenous community leader, Michoacán, 2023 (name and exact date and location withheld).

“Avocados From Mexico make everything better. Talk about holy guacamole!” – Avocados From Mexico.4“Avocados from Mexico Make Everything Better in an Epic Way in New Big Game Ad,” PR Newswire (news provided by Avocados From Mexico), February 8, 2023, https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/avocados-from-mexico-make-everything-better-in-an-epic-way-in-new-big-game-ad-301742217.html (accessed September 18, 2023).

The next time you eat guacamole there is a serious risk it will contain avocado that was grown on illegally deforested land, using stolen water, in a region of Mexico where Indigenous people and other residents face violence and intimidation for defending the environment.

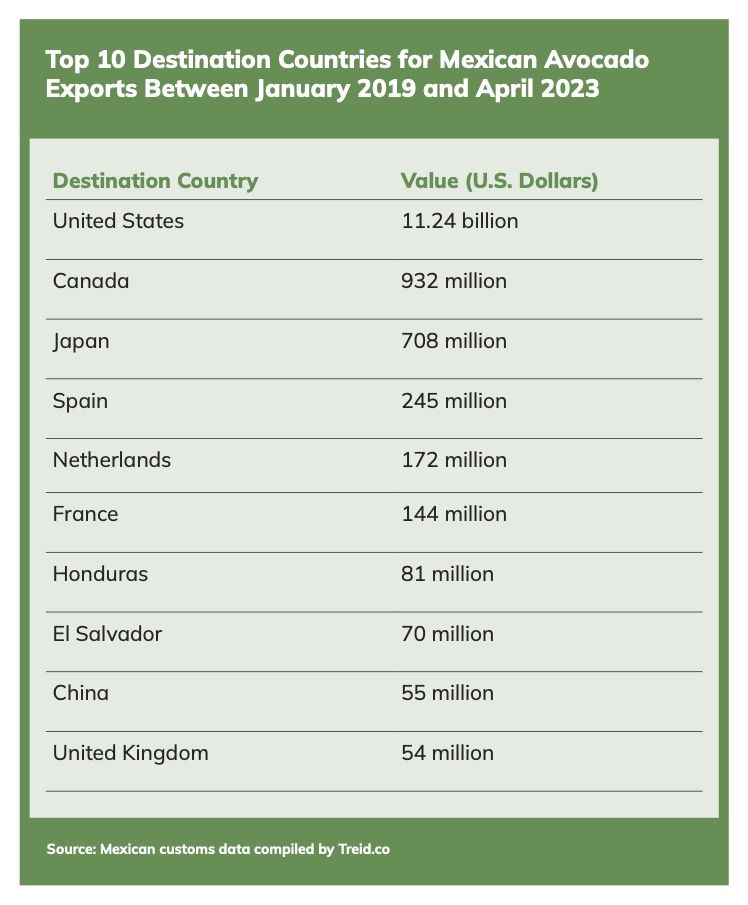

The world’s leading producer and exporter of avocados, Mexico supplies four out of five avocados eaten in the United States in exports worth US$3 billion per year. Mexican avocados are also increasingly reaching other international markets, with more than US$2 billion exported to Europe, Canada, and Asia over the past five years. U.S. avocado consumption has tripled since 2000, partly driven by the industry’s vigorous marketing campaigns, including claims of Mexican avocados’ “sustainability.” A 2023 Super Bowl ad showed Eve holding the fruit in the Garden of Eden, with the slogan that avocados “make everything better.”

Yet growing international demand has fueled the widespread clearing of forests in Michoacán and Jalisco, the two states that produce all Mexican avocados exported to the United States. Avocado producers use enormous amounts of water, and many illegally extract it from streams, rivers, springs, and underground aquifers to irrigate their orchards. The deforestation and water capture have taken a serious toll on local populations—contributing to water shortages and increasing the risks of lethal landslides and flooding.

Mexican authorities are failing to contain the destruction. Major importers and supermarkets are selling avocados produced on deforested lands. The U.S. government has the means to help but has turned a blind eye—despite U.S. climate-change commitments to end global deforestation, as well as long-standing commitments to promote human rights, including those of Indigenous Peoples.

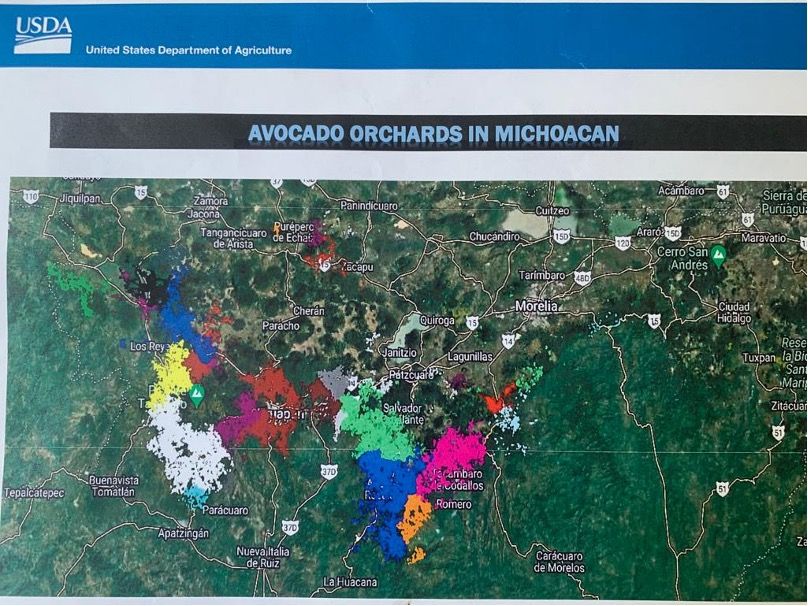

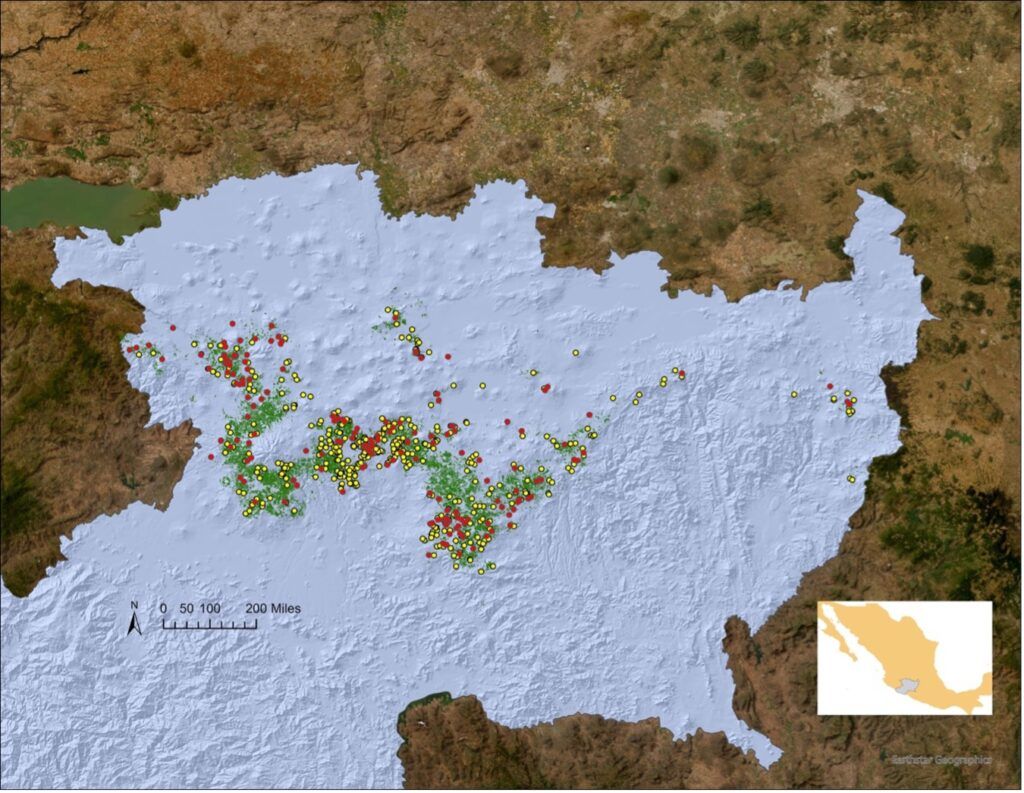

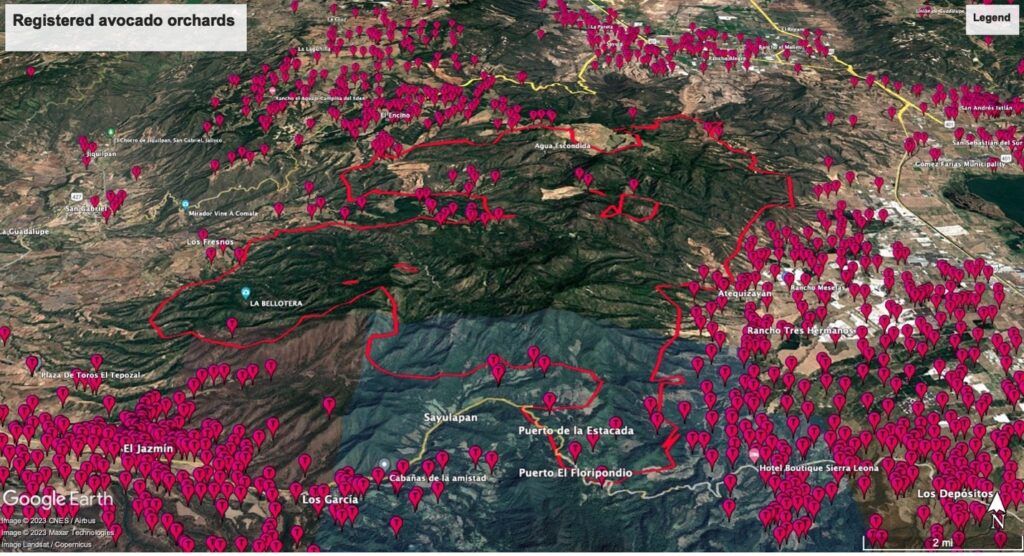

These findings are based on extensive field research by Climate Rights International across 18 municipalities in Michoacán and Jalisco, interviews with nearly 200 people, and a review of previously unpublished U.S. and Mexican government records, including maps of the more than 50,000 avocado orchards certified to export to the United States.

Virtually all the deforestation for avocados in Michoacán and Jalisco over the past two decades has violated Mexican federal criminal law, which prohibits “land-use change” of forested areas to agricultural production without government authorization. The additional crime of intentionally setting forest fires frequently facilitates the deforestation. The conversion of natural forests to avocado-tree plantations releases climate-warming greenhouse gases, reduces carbon storage, and undercuts biodiversity and the replenishment of aquifers.

Throughout the communities Climate Rights International visited, we encountered widespread concern, indignation, and outrage that local forests were being destroyed and water supplies depleted and stolen. Yet these sentiments were usually matched—and sometimes outweighed—by another: fear. Climate Rights International documented repeated threats and attacks against residents who have opposed avocado-driven environmental degradation. It was common knowledge among local residents that the brutal organized crime groups that dominate the region have multiple links to parts of the industry. People were afraid that by taking action to defend the environment they would put themselves in danger—and many have chosen not to for this reason.

Indigenous Purépecha communities have collectively mobilized to protect forests, but they too have been thwarted by violence and intimidation. The assaults on Indigenous communities infringe on their human right, as Indigenous Peoples, to participate in decision-making in matters that affect their lands and resources. As the minutes of one community assembly put it, deforestation for avocado production is “destroying the ecological equilibrium of communal lands.”5Minutes of Extraordinary General Assembly in the Indigenous Population of Ocumicho, Charapan Municipality, Michoacán, (Acta de asamblea general extraordinaria de la población indígena de Ocumicho municipio de Charapan, Michoacán), June 14, 2020.

Environmental officials in both Michoacán and Jalisco recognize that avocado production is a central cause of deforestation and environmental destruction in their states. Yet, Mexican authorities often fail to enforce environmental laws in avocado-growing regions. One reason is that officials fear being targets of threats and violence if they try to rein in illegal deforestation and water theft. Another reason is corruption, especially in state criminal investigations and prosecutions in Michoacán, according to state and federal officials and residents.

Given the challenges around local enforcement, precluding deforestation-linked avocados from reaching multibillion dollar markets—especially in the United States—is key to containing the problem. That was the consensus view among Mexican officials and community leaders, who told Climate Rights International that blocking access to these markets would significantly reduce the incentive to destroy forests—or to attack residents defending them.

In 2021, top Mexican environmental officials proposed such a policy to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) plant inspection service’s regional director in Mexico. This would have entailed adding a no-illegal-deforestation requirement to the existing agreement between the two governments, under which each avocado orchard that exports to the United States must be certified by U.S. and Mexican authorities as meeting criteria that currently relate exclusively to pest control. But U.S. officials did not act on the proposal.6Transparency law response by Mexico’s National Forest Commission (CONAFOR) to request number 330009623000174, April 27, 2023. Instead, as this report shows, the United States routinely certifies illegally deforested orchards to export to U.S. consumers.

Compounding the problem, the U.S. government approved the state of Jalisco to start exporting avocados to the United States in 2022, without adopting measures to address the risk that, as an internal U.S. government report alerted at the time, the approval was “likely to increase deforestation” in Jalisco, as “market pressures” had done in Michoacán.7Email from U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) personnel to Kelly Milton, Assistant USTR for Environment and Natural Resources, April 4, 2022, containing “USMCA Environment Monthly Newsletter,” provided by USTR in response to FOIA request on March 30, 2023.

Companies in the United States, Mexico, and elsewhere bear significant responsibility for the deforestation. Climate Rights International found that, despite making strong sustainability claims, many major companies are taking little or no action to prevent contamination of their supply chains by deforestation-linked producers in Mexico. Previously unpublished Mexican government records indicate that in 2022 orchards containing illegally deforested land supplied avocados to the U.S.-based companies Calavo Growers, Fresh Del Monte Produce, Mission Produce, and West Pak Avocado. The companies have, in turn, supplied Mexico-sourced avocados to major supermarket chains, including Walmart, Whole Foods, Kroger, Albertsons, Costco, Target, and Trader Joe’s.

The inaction by corporations and government officials is inexcusable. U.S. and Mexican authorities have maps of all the export-certified orchards, and any corporation committed to rooting out deforestation from their supply chains could obtain them—just as Climate Rights International did. Comparing these maps with satellite imagery, authorities could identify recently deforested orchards and block them from export-certification, and companies could identify and block them from their supply chains. Doing so wouldn’t wreck Mexico’s avocado industry: while the recent deforestation is widespread and severely impacts many people and the environment, most existing orchards would not be affected by such policies, as they are on lands that have long been dedicated to farming. The policies would, however, dramatically reduce the incentive to cut down more trees to meet the growing demand for avocados.

The deforestation and human rights harms in Mexico are symptomatic of a much broader problem that is central to the climate crisis: the lack of international and national regulations and policies to end deforestation for agricultural commodities such as beef, soy, palm oil, and avocados. Urgently enacting and implementing such regulations and policies is essential to averting climate catastrophe, and to protecting the rights of populations where the commodities are produced.

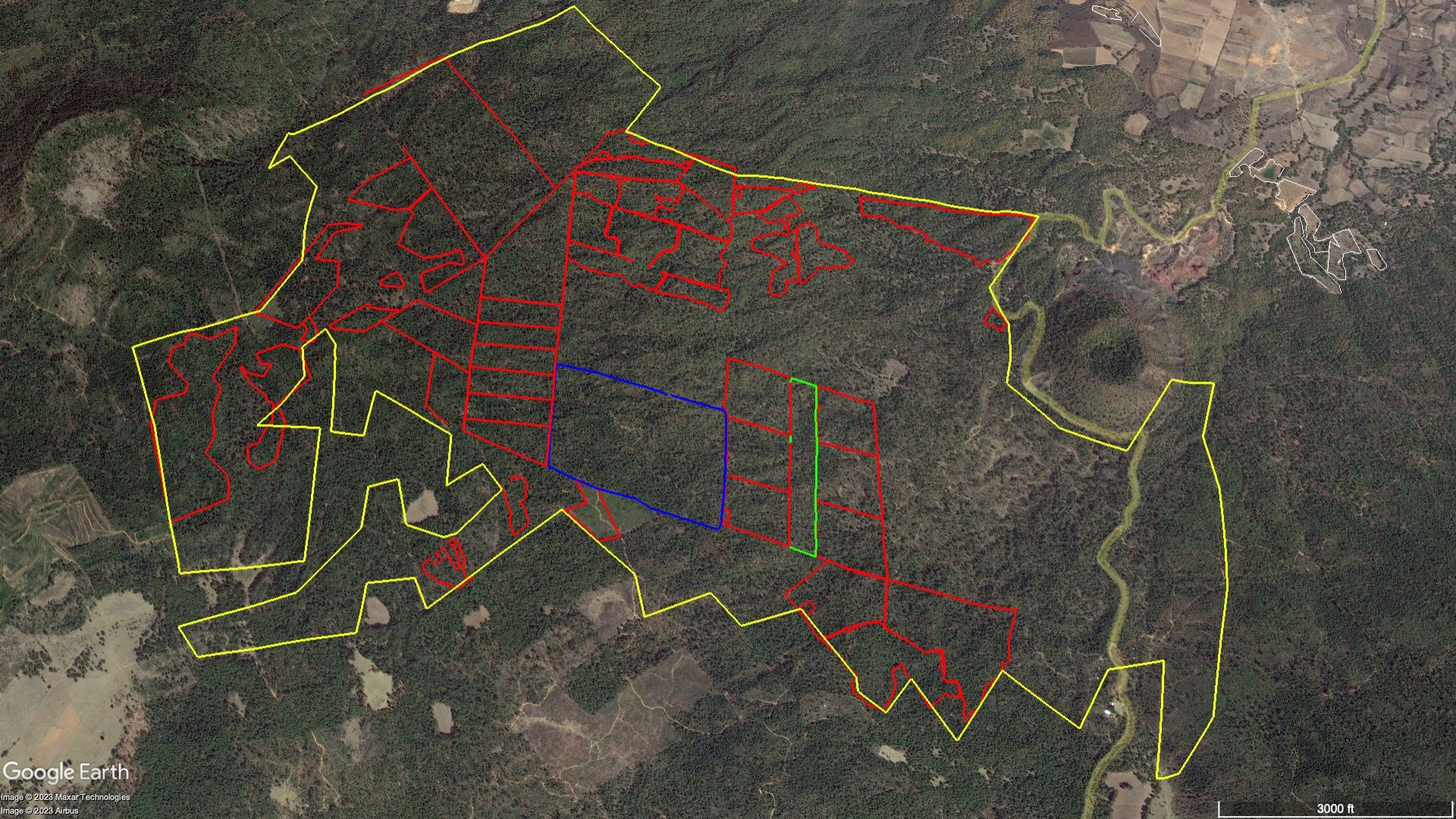

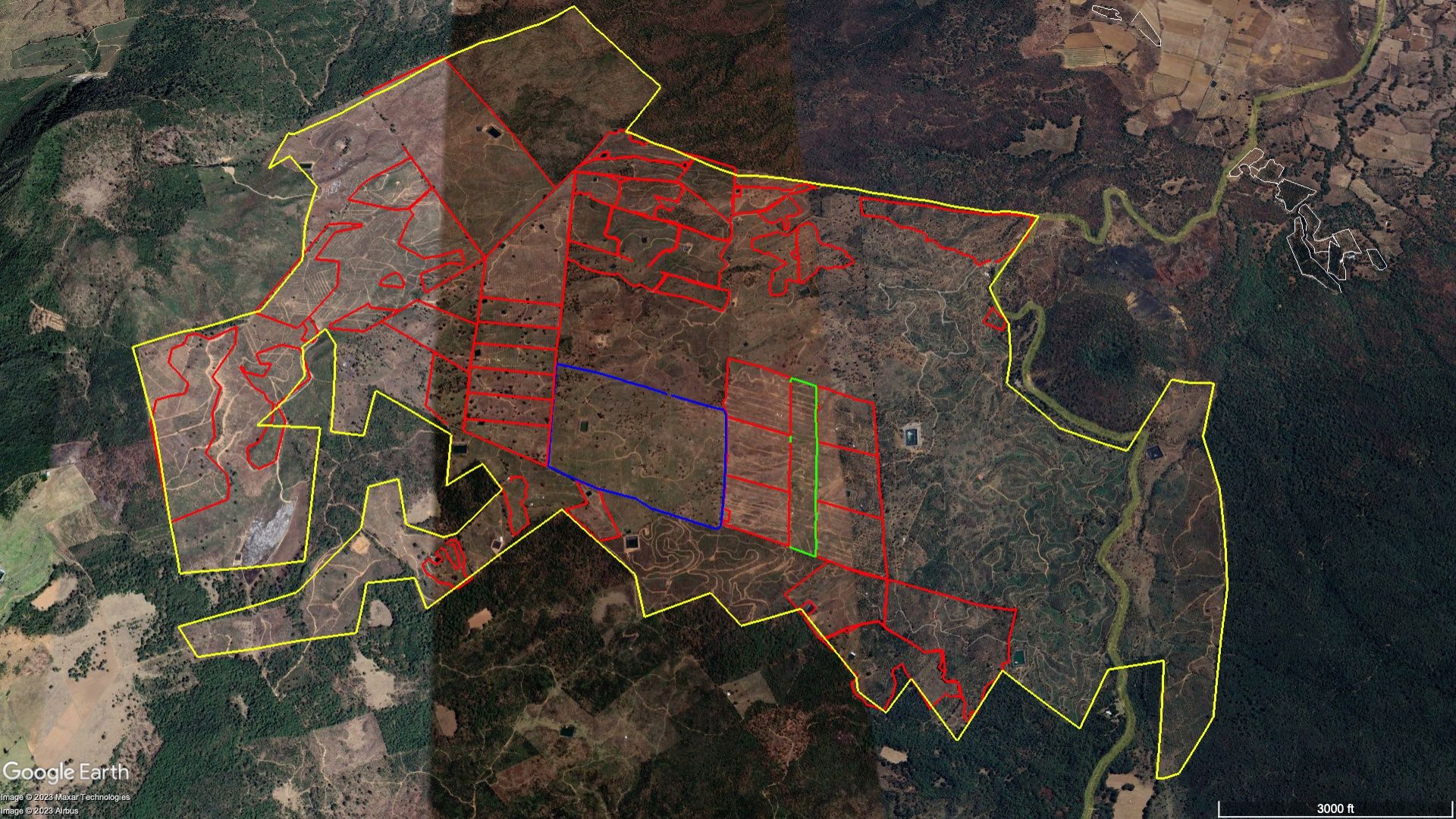

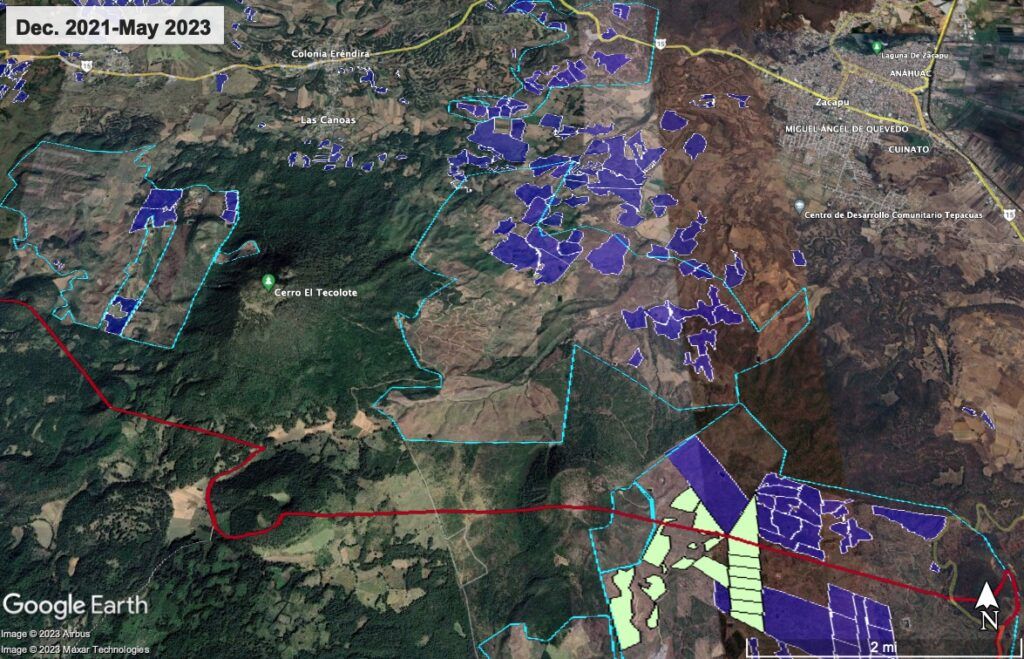

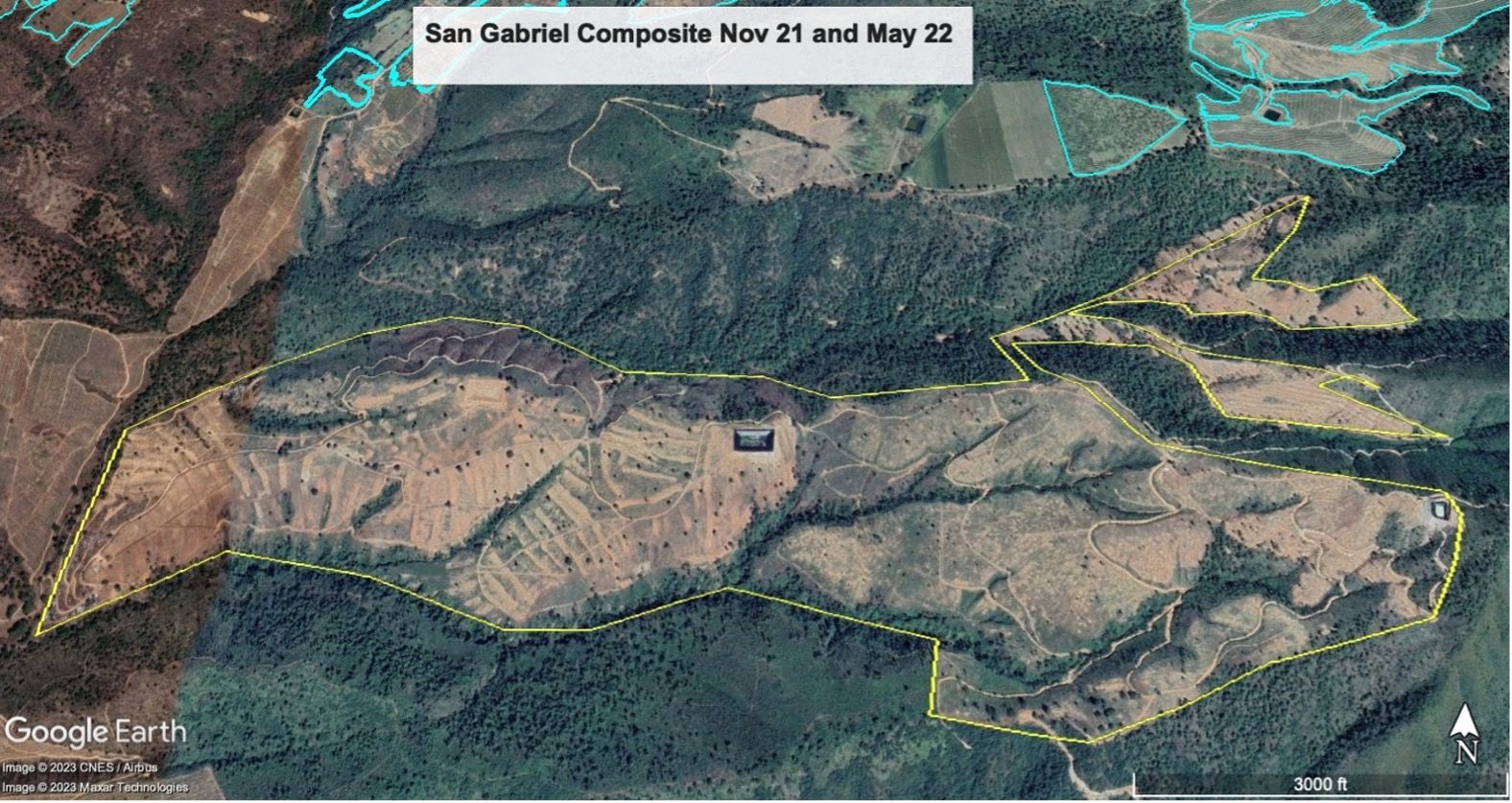

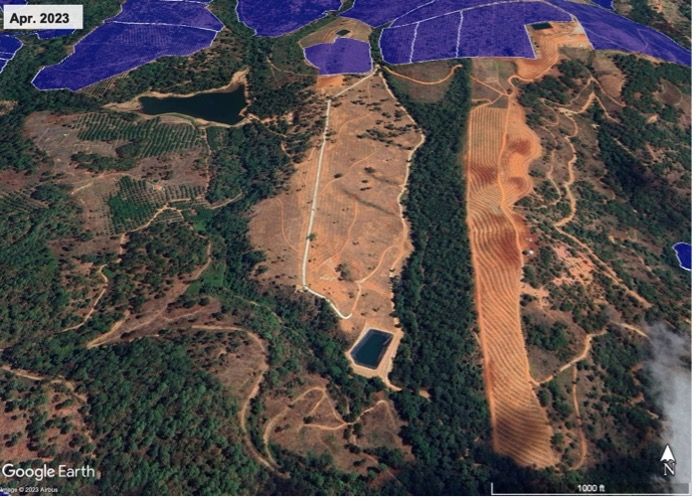

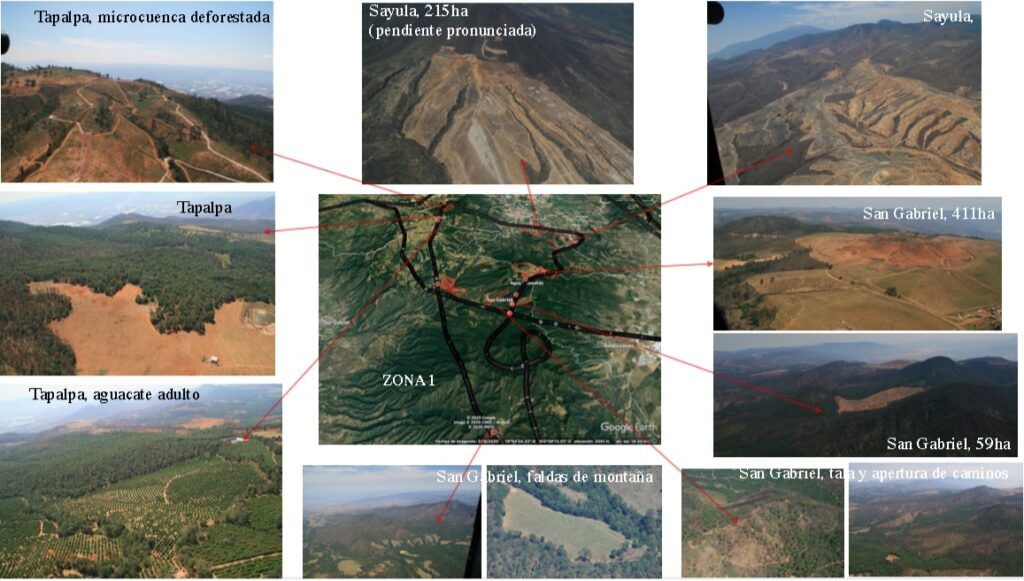

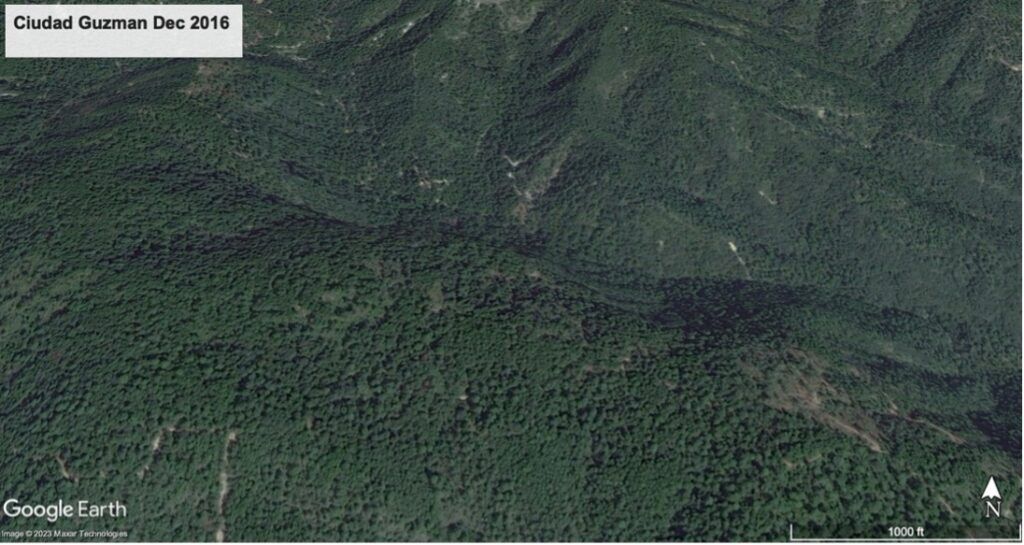

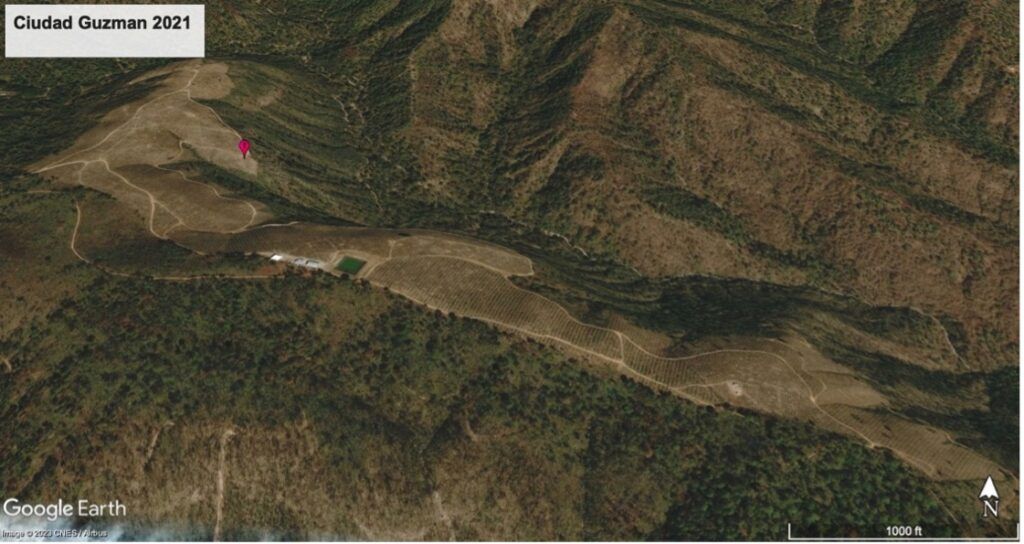

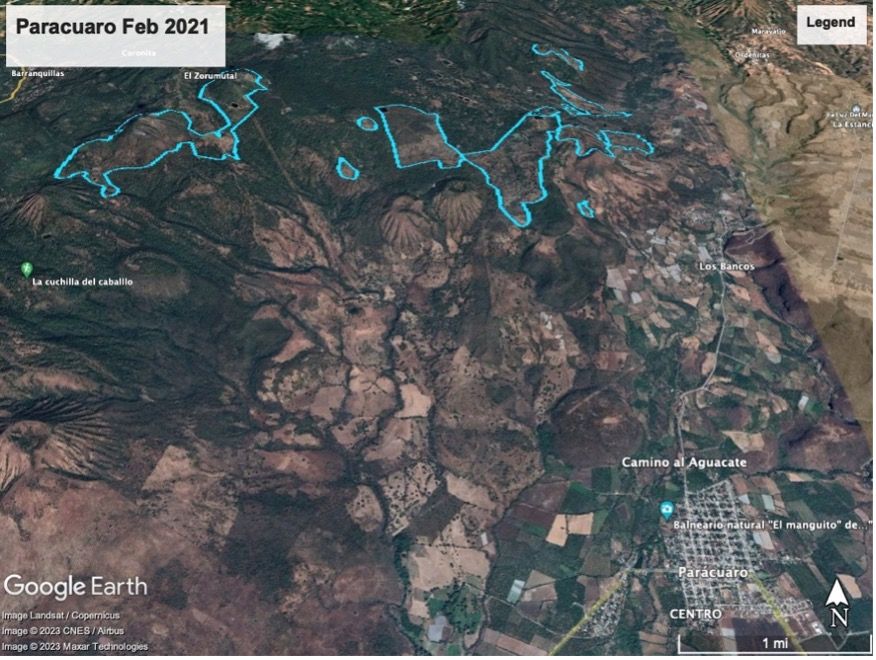

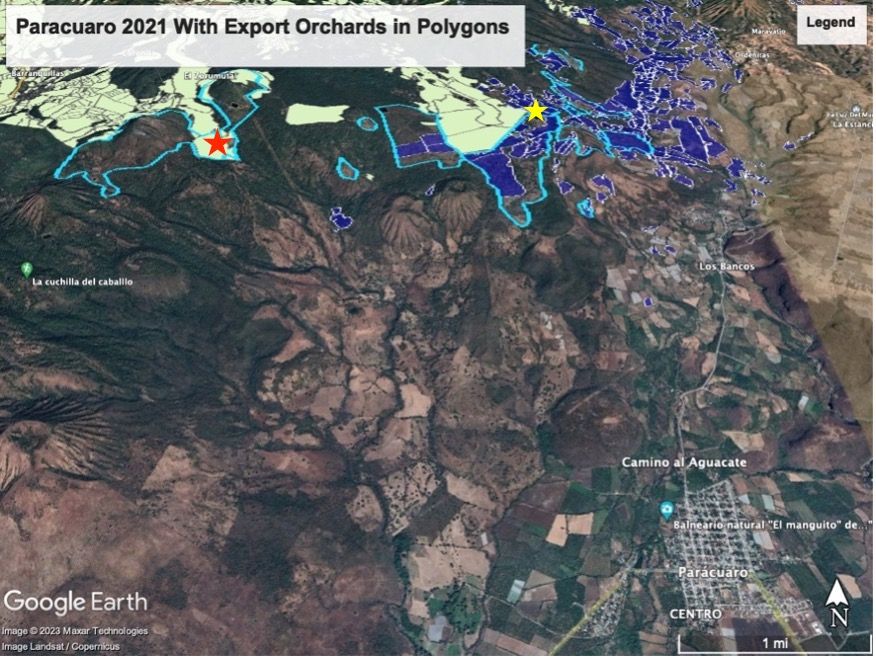

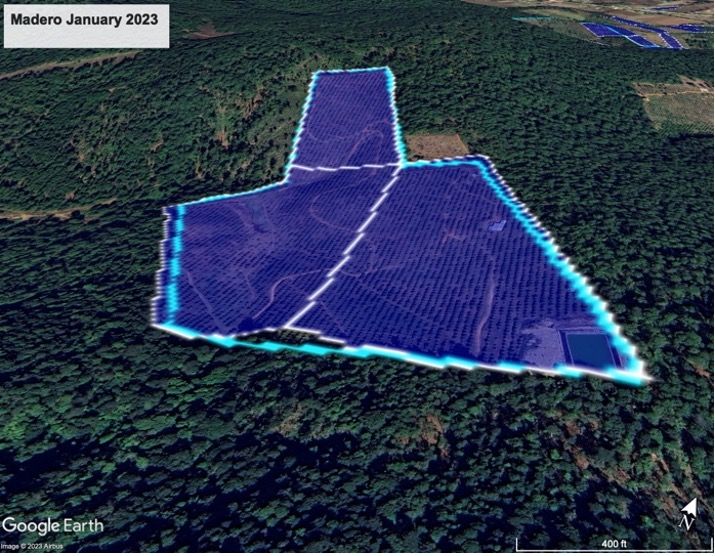

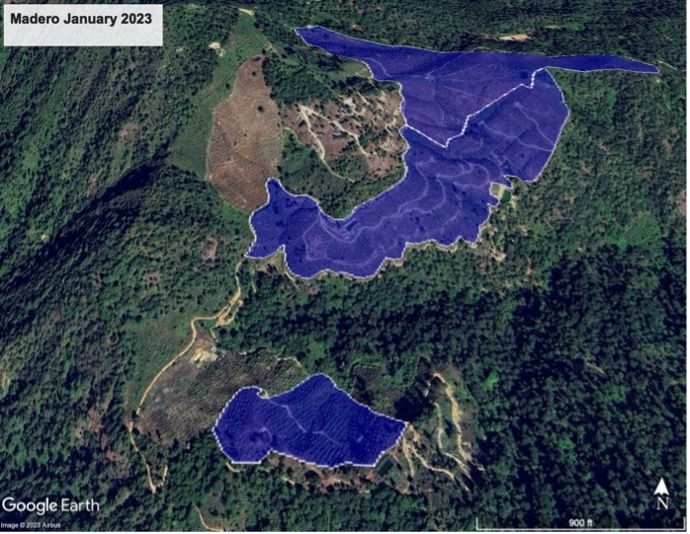

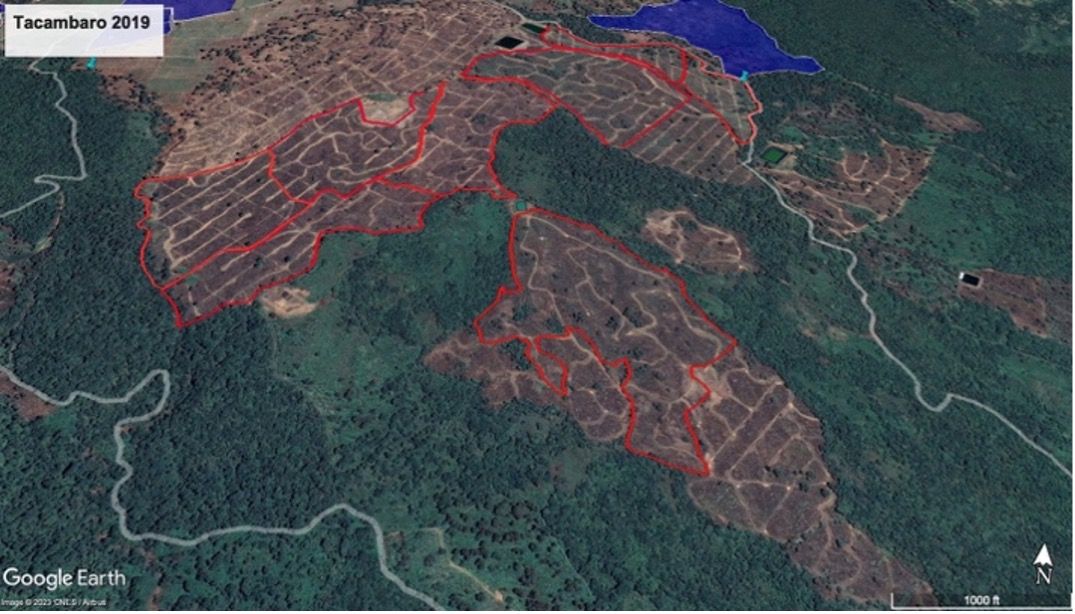

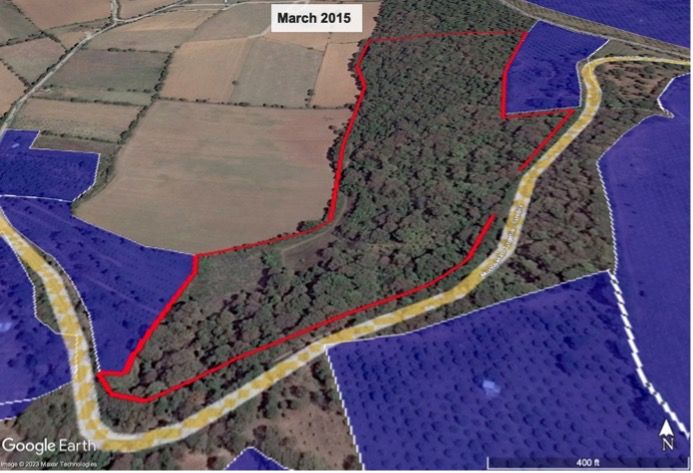

The following two Google Earth satellite images show forests illegally cleared in Michoacán to plant avocado orchards, many of which have been certified to export to the United States.

The “before” image, from 2015, shows an area outside of Zacapu, Michoacán. The area outlined in yellow is 2,705 acres. The “after” image is from the same area, and mostly from 2023. It reveals deforestation throughout the yellow-outlined 2,705-acre area since 2015. The red, blue, and green outlines are government maps of avocado orchards certified to export to the United States as of January 2023. Government shipping records indicate that in 2022 the orchard containing deforested land outlined in blue provided 27,510 kilograms of avocados to Mission Produce, while the orchard with deforested land outlined in green provided 25,455 kilograms to West Pak.8Records of “harvest logs” (“bitacoras de cosecha”) provided in transparency law response from National Service of Health, Food Safety and Quality (SENASICA) to request number 330028323000180, June 27, 2023. Orchard HUE08161070708 supplied Mission Produce and orchard HUE08161070572 supplied West Pak.

The total amount of avocado-driven deforestation in Michoacán and Jalisco over the past decade very likely exceeds 40,000 acres (16,000 hectares)—and could be more than 70,000 acres—according to Climate Rights International’s review of government estimates, a study by environmental geographers produced for this report, and of satellite imagery. For context, one acre is nearly the size of an NFL football field, and almost three-quarters the area of a FIFA soccer field.

Over the past decade, Mexican officials have made estimates of annual avocado-driven deforestation in Michoacán that have ranged from 2,900 acres per year to as high as 24,700 acres per year. Michoacán’s Secretary of Environment, Alejandro Méndez, has said that the state’s “most serious environmental issue is the indiscriminate change of land use for avocado crops.”9“Avocado: Business, Ecocide and Crime: Part 1,” (Aguacate: negocio, ecocidio y crimen: Parte 1), UGTV Territory Reporting, Sept. 7, 2022, video clip, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PaaaJXAx6NQ (accessed September 12, 2023). Eighty-five percent of the area of avocado production in the state is certified for U.S.-export, according to government statistics.

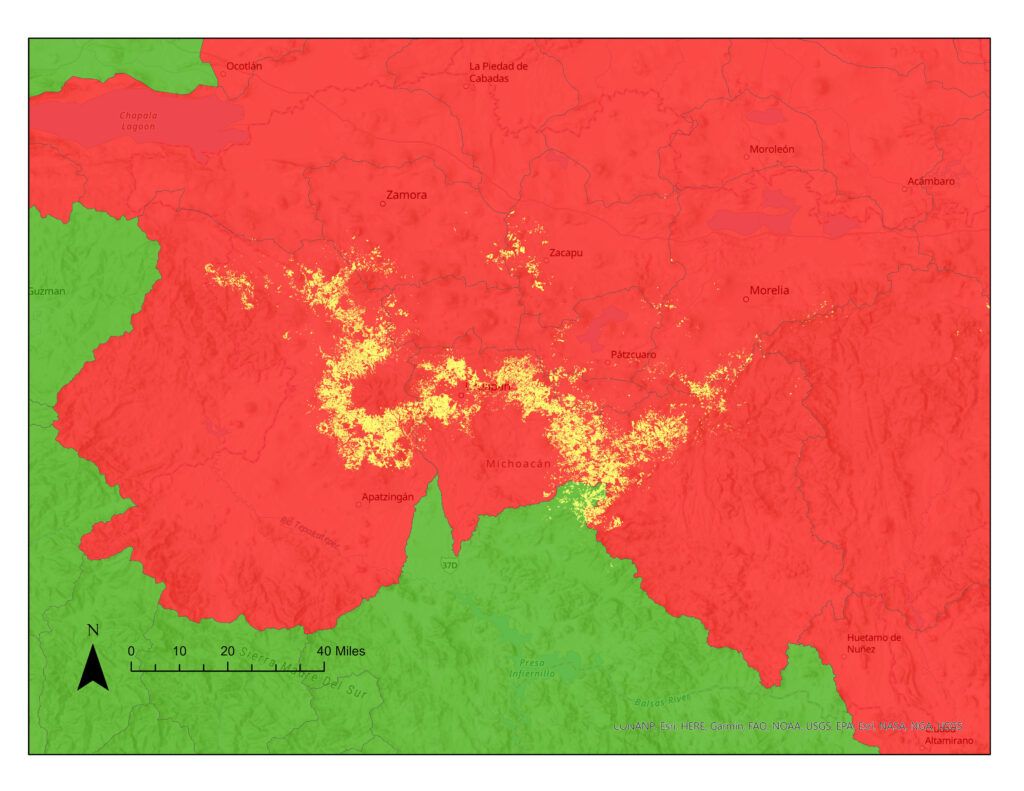

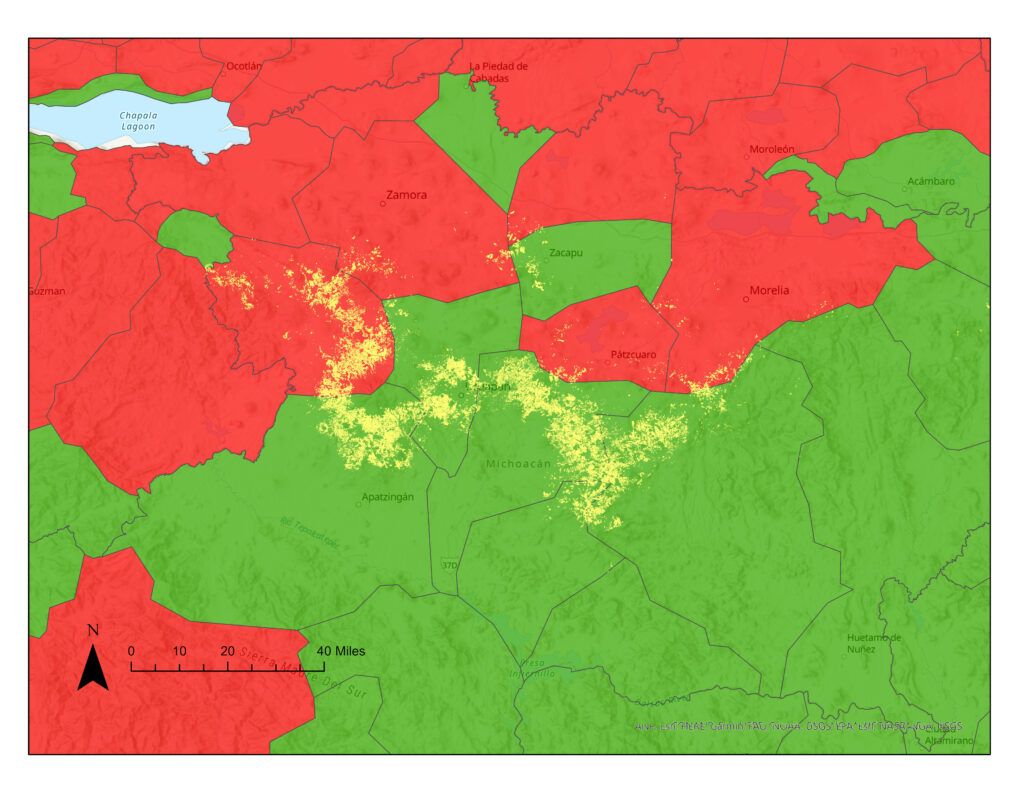

Environmental geographers from the University of Texas at Austin estimate that more than 25,000 acres of Michoacán avocado orchards certified to export to the United States in 2023 are located on land that was covered by forest in 2014.10They produced the estimate for this report by comparing previously unpublished official maps—obtained by CRI—of avocado orchards certified to export to the United States as of February 2023, with Mexican federal government maps of all agricultural lands in Michoacán for the period of 2014-2015, and academic land-use maps identifying forest lands in Michoacán as of 2014. (The study used the 2014 cut-off date because it is the most recent year for which an academic land-use map of Michoacán identifying forestlands is available.) It follows from their conclusion that these estimated 25,000 acres have either been illegally deforested since 2014 or been certified while still containing some forest that could be cleared in the future to produce additional avocados for export. Climate Rights International’s review of the satellite imagery suggests that most of the acres have in fact been illegally cleared.

In addition to the 25,000 acres within export-certified orchards found by the University of Texas at Austin geographers, Climate Rights International identified thousands more acres of forest cleared in Michoacán that are apparently destined for avocado production, much of which is very likely to be certified for export to the United States. There is typically a lag between the creation of an orchard and its certification, as producers don’t seek to certify until their newly planted avocado trees start producing, which takes at least two years.

Prior to 2014, decades of avocado expansion in Michoacán had already caused at least 54,000 acres of deforestation, according to a government study, and possibly as many as 121,000 acres, according to an academic study. The government study highlighted, in 2012, that avocado production in Michoacán had resulted in “drastic[] land-use change and deterioration of the environment.”11Mexico’s National Institute for Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research (INIFAP), “Impact of Land-Use Change From Forest to Avocado,” (“Impacto del cambio de uso de suelo forestal a huertos de aguacate”), August 2012, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265125083_Impacto_del_cambio_de_uso_del_suelo_forestal_a_huertos_de_aguacate_IMPACT_OF_FOREST_LAND_USE_CHANGE_TO_AVOCADO_ORCHARDS, p. 5 (accessed July 11, 2023).

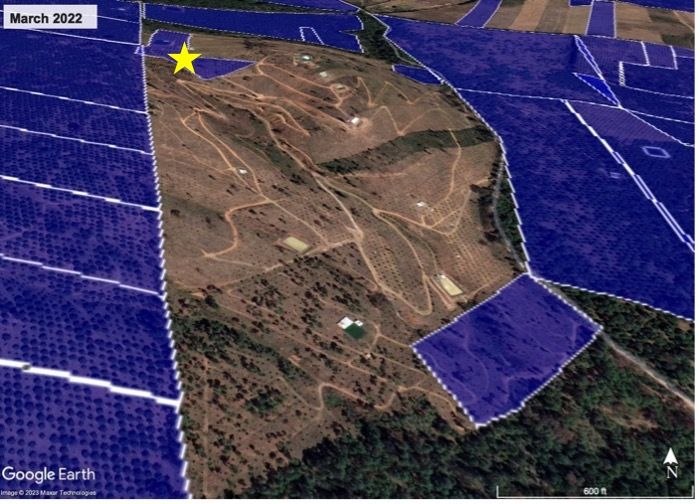

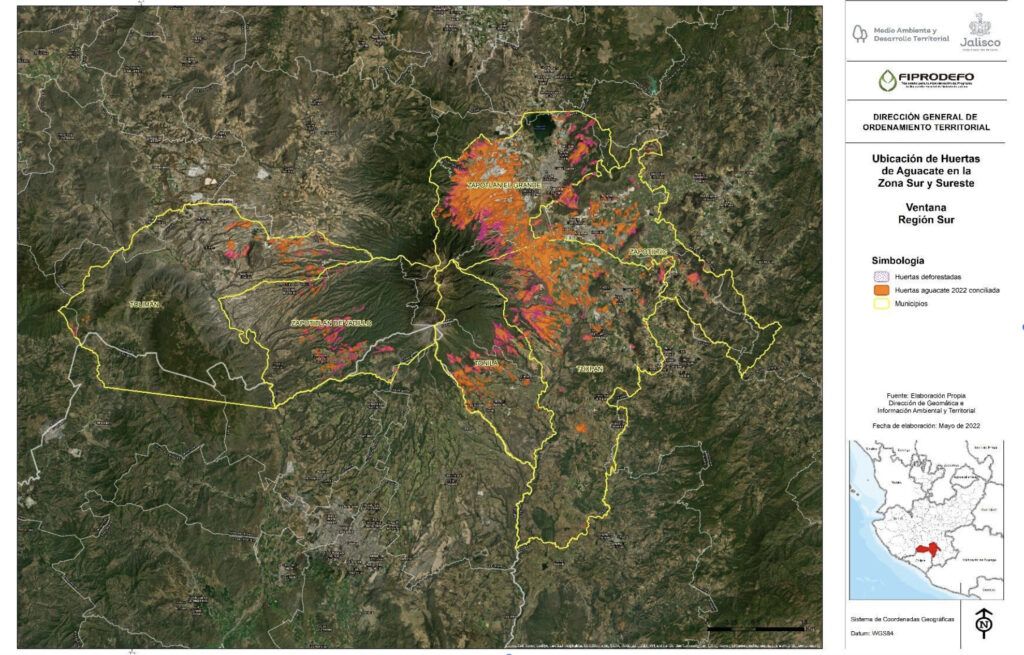

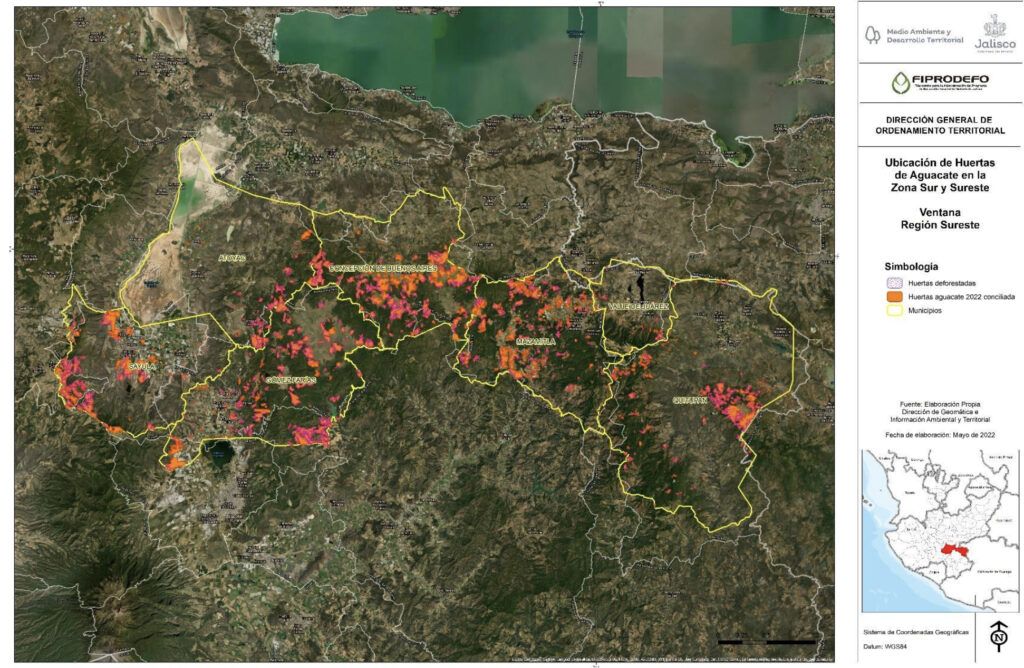

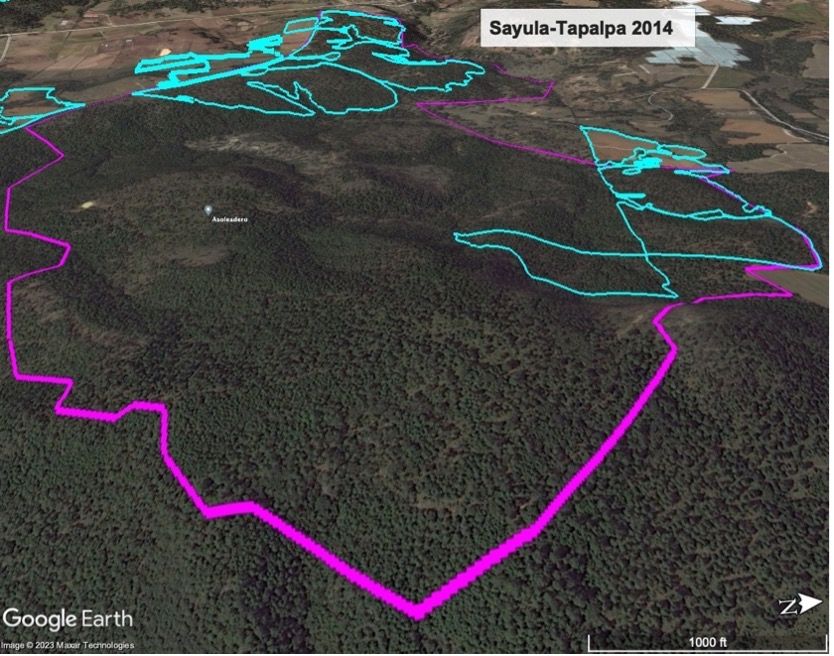

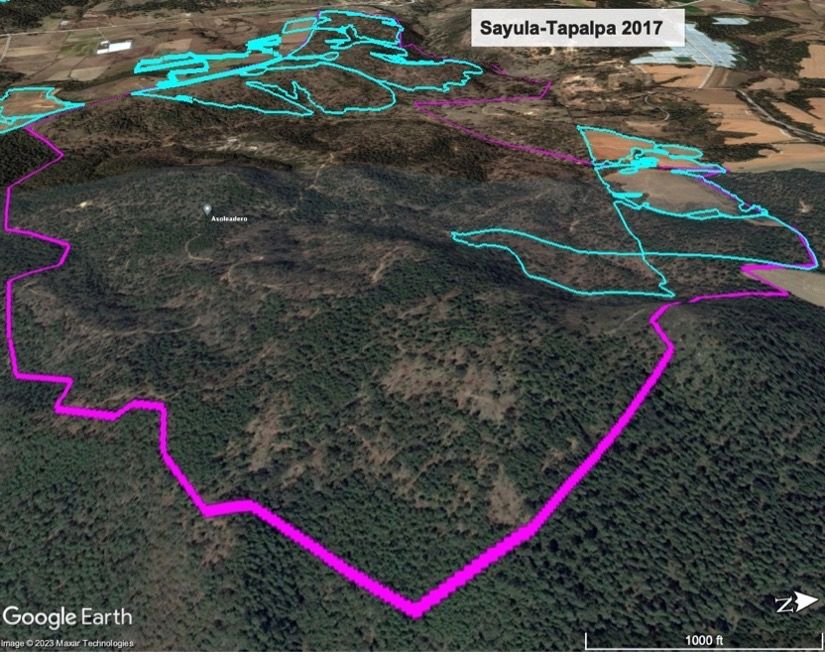

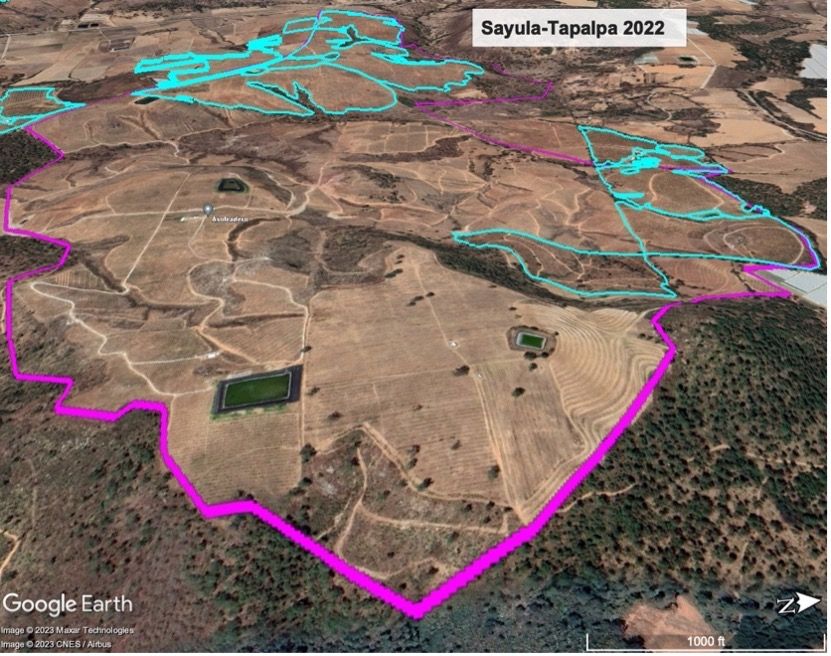

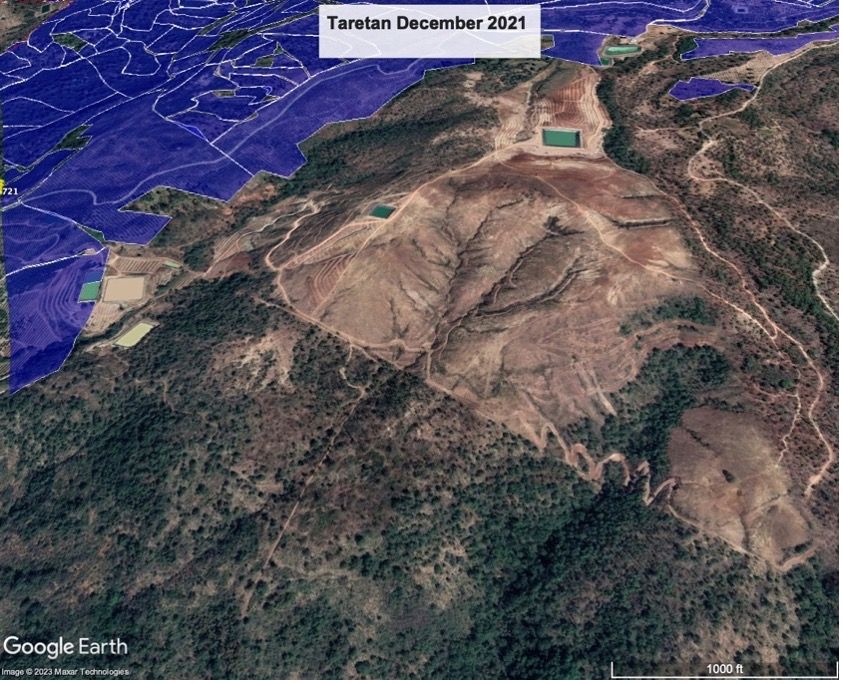

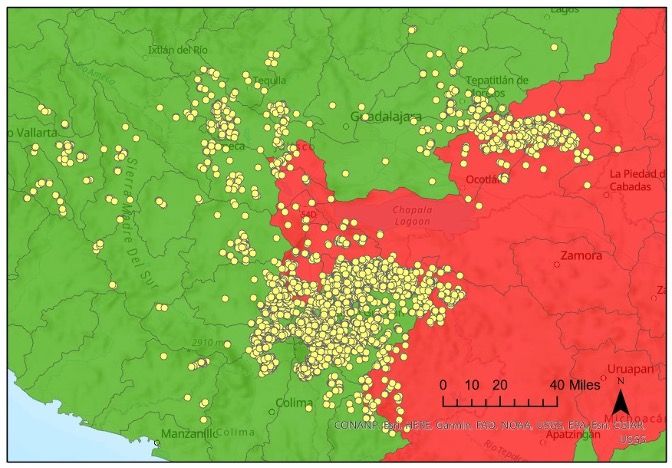

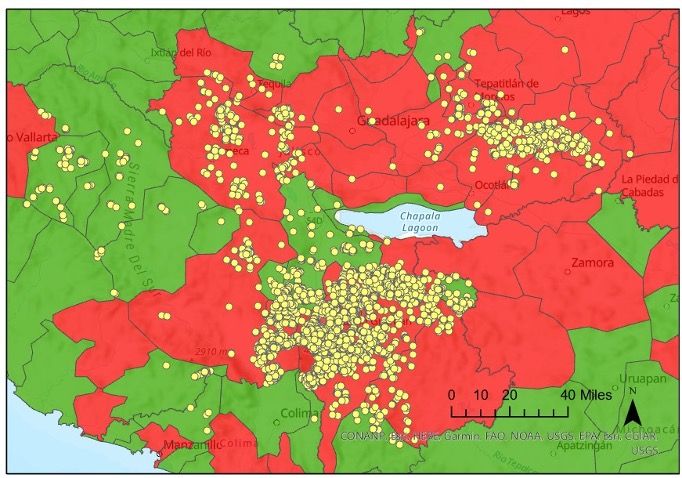

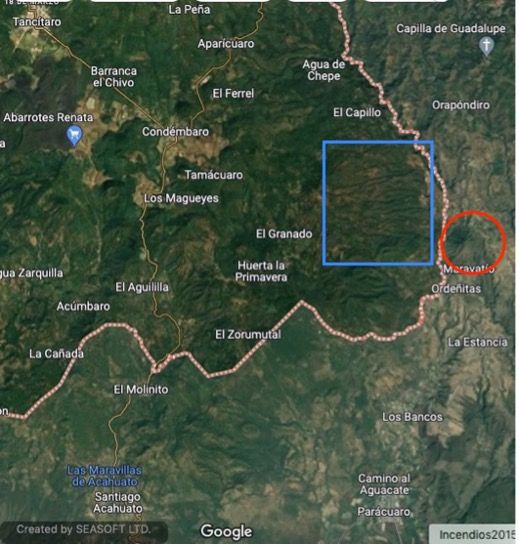

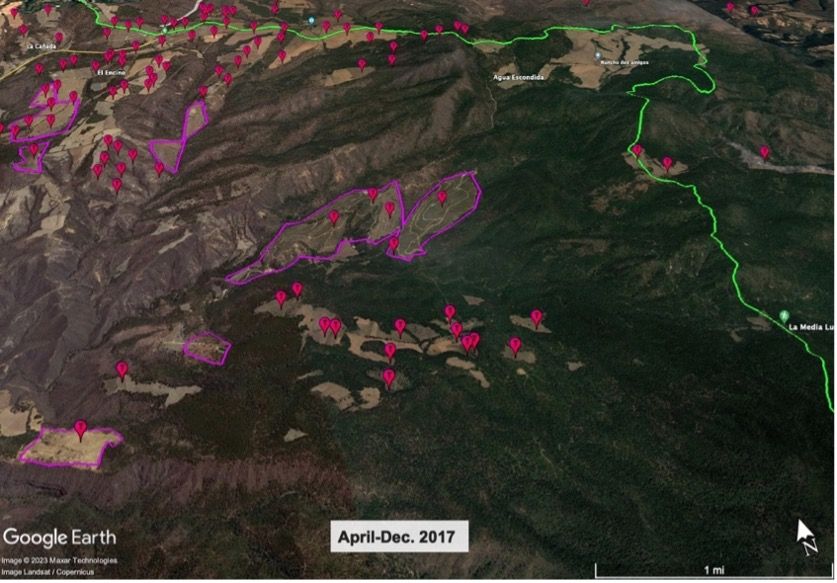

In Jalisco, avocado production is similarly “one of the main direct causes of deforestation,” according to Jalisco’s Secretary of Environment and Territorial Development (SEMADET).12Carmen Gómez Lozano, Director of Biological Corridors and Watersheds, SEMADET, contribution to panel discussion “Environmental Impact of the Production and Trade of Avocados Between Mexico (Jalisco) and Europe,” online event hosted by the Embassy of the Netherlands in Mexico, May 9, 2023, attended by CRI personnel. A study by the agency found that avocado orchards caused at least 12,744 acres of deforestation in Jalisco between 2017 and the first quarter of 2022. The analysis found that the deforestation for avocado production in the state during that period could actually be as high as 47,251 acres, when taking into account likely but unverified avocado orchards, according to a former official with direct knowledge of the analysis.

Overall, Climate Rights International identified U.S.-export certified avocado orchards containing land deforested since 2014 in 41 of the 46 Michoacán municipalities, and 8 of the 10 Jalisco municipalities, approved to export to U.S. consumers as of 2023. (The seven municipalities where we did not find such orchards contain just 0.2% percent of the area of avocado plantings in both states reported by the government.)

Tens—if not hundreds—of thousands of acres of forest in the two states remain at risk of deforestation for avocado exports, according to academic studies.13See, e.g., Audrey Denvir, “Avocado expansion and the threat of forest loss in Michoacán, Mexico under climate change scenarios,” Applied Geography, Volume 151, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2022.102856 (accessed August 21, 2023).

Our analysis of government records indicates that, over the past two decades, all of the deforestation for avocados in Michoacán, and virtually all of it in Jalisco, has been illegal—in violation of Mexican criminal and administrative laws. Mexican law requires a federal permit to convert forests to agricultural uses. No such permits have been issued in Michoacán for at least two decades; none were issued in Jalisco between 2011 and 2022; and just nine were issued in the state for avocado plantations between 2000 and 2010, according to records obtained by Climate Rights International through Mexico’s transparency law.14Transparency law responses from Mexico’s Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) to requests numbers 330026723000053 (Michoacán) and 330026723000054 (Jalisco), February 7, 2023. Senior officials also confirmed the absence of authorizations in Michoacán.15Climate Rights International (CRI) interview with Rosendo Caro, General Director of Michoacán’s State Forest Commission, Morelia, Michoacán, December 15, 2022; CRI interview with state prosecutor’s office official, Morelia, Michoacán, December 15, 2022; CRI interview with Alejandro Méndez, Michoacán’s Secretary of Environment, Morelia, Michoacán, December 16, 2022; CRI interview with senior federal environmental official, Morelia, Michoacán, December 16, 2022; CRI interview with senior federal environmental official, Morelia, Michoacán, December 16, 2022. See also Pedro Zamora Briseño, “Michoacán: the Environmental Disaster of the ‘Green Gold,’” (“Michoacán: El desastre ambiental del ‘oro verde,’”); Proceso, Oct. 18, 2021, https://www.proceso.com.mx/reportajes/2021/10/18/michoacan-el-desastre-ambiental-del-oro-verde-274116.html (accessed July 12, 2023).

The deforestation often involves intentionally setting the forest on fire, which is also a crime under Mexican law. Climate Rights International identified 185 forest fires in Michoacán over the past decade that directly overlapped with or are right next to a U.S.-export certified orchard, for which the Mexican government’s determination of the cause of the fire strongly implies they were ignited to clear forest and vegetation for avocado production. “When there’s a fire, it’s for avocado. All of them are started intentionally,” said a resident of an avocado-growing region in Jalisco.

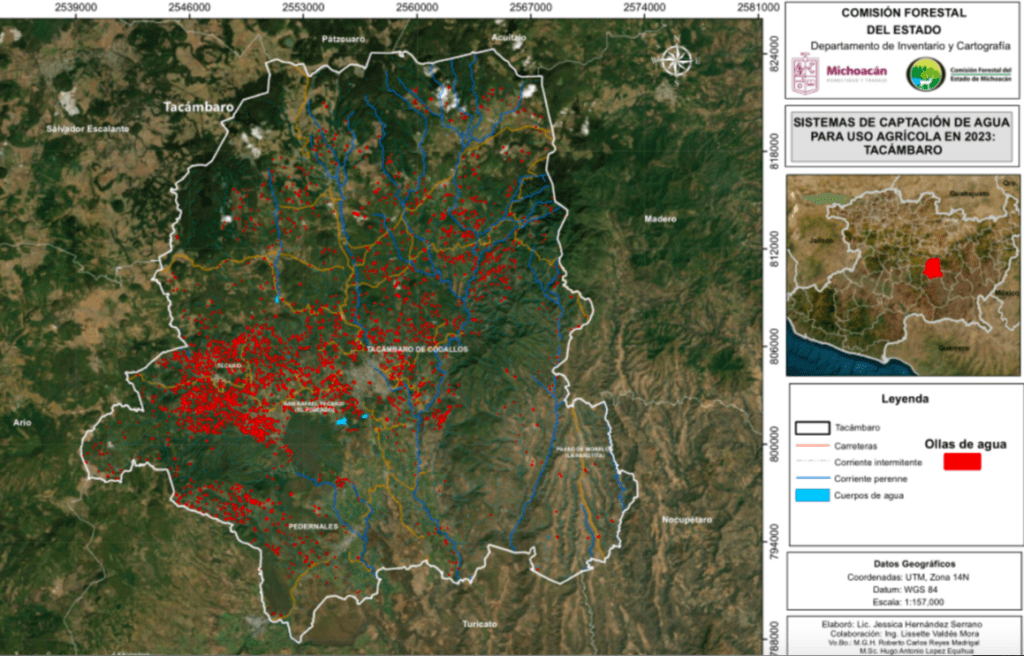

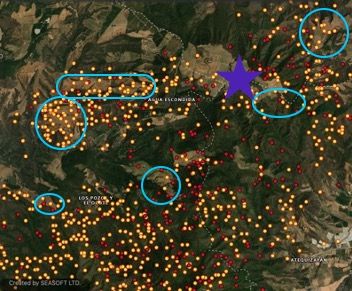

Water theft by avocado growers to irrigate their orchards often compounds the illegal deforestation. Many growers in Michoacán and Jalisco extract water from streams, rivers, springs, and wells without required licenses issued by Mexico’s federal concession system.

Interviews with residents and officials, Climate Rights International site visits, and academic studies suggest the problem is widespread. For example, Michoacán’s former top water official, and municipal officials from an avocado-producing hub in Jalisco, each estimated that at least half of the wells in their jurisdictions were unlicensed.16Arturo Molina, “Water Wells Threaten Aquifers in Michoacán: Half of Them are Illegal,” (“Pozos de agua amenazan mantos acuíferos en Michoacán: la midad de ellos son ilegales”), La Voz de Michoacán, Feb. 22, 2020, https://www.lavozdemichoacan.com.mx/michoacan/medio-ambiente/pozos-de-agua-amenazan-mantos-acuiferos-en-michoacan-la-mitad-de-ellos-son-ilegales/ (accessed July 12, 2023); CRI interviews with Zapotlán el Grande officials, Ciudad Guzman, Jalisco, March 17, 2023 (names withheld). The theft thwarts the concession system Mexico has in place to protect watershed (surface water) and aquifer (underground water) supplies, and thus residents’ human right to water.

The illegal deforestation and enormous, frequently illegal, capture and use of water by many avocado producers have caused or contributed to water shortages and the risk of lethal flooding and landslides for local residents across Michoacán and Jalisco.

The clearing of trees for avocado production jeopardizes water availability, as forests play a vital role in helping rainwater enter the ground and recharge the aquifers that supply communities through natural springs and wells. Moreover, to grow just one average, medium-size avocado requires an amount of water equivalent to what a person would use taking a nearly 20-minute shower.17A recent study of avocado production in Uruapan, Michoacán found an average water footprint of 744.3 liters per kilogram of avocados. Alberto Gómez-Tagle et al, “Blue and Green Water Footprint of Agro-Industrial Avocado Production in Central Mexico,” Sustainability 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159664 (accessed September 11, 2023). The median size of a Hass avocado for export is about 205-265 grams, according to APEAM. APEAM X feed, https://twitter.com/apeamac/status/1123959475990351872 (accessed September 12, 2023). This means there are about 4.25 median-sized avocados per kilogram, and the water footprint would be 175.1 liters per avocado. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports that the standard showerhead uses 9.46 liters per minute, meaning that 175.1 liters would be a 18.5 minute shower. EPA, “Showerheads,” https://www.epa.gov/watersense/showerheads#:~:text=Did%20you%20know%20that%20standard,no%20more%20than%202.0%20gpm (accessed September 12, 2023). So producing avocados at the scale that makes Mexico the leading U.S. and global supplier drains—often via water theft—an enormous amount of water from ecosystems. In the words of a federal environmental official, avocado consumption is “at the cost” of “drying up watersheds.”18 CRI group interview with SEMARNAT officials, Mexico City, March 21, 2023. Or, as one community leader put it, “They are exporting our water in the form of fruit.”19CRI group interview with community leaders and residents, Jalisco, 2023 (names and exact dates and locations withheld).

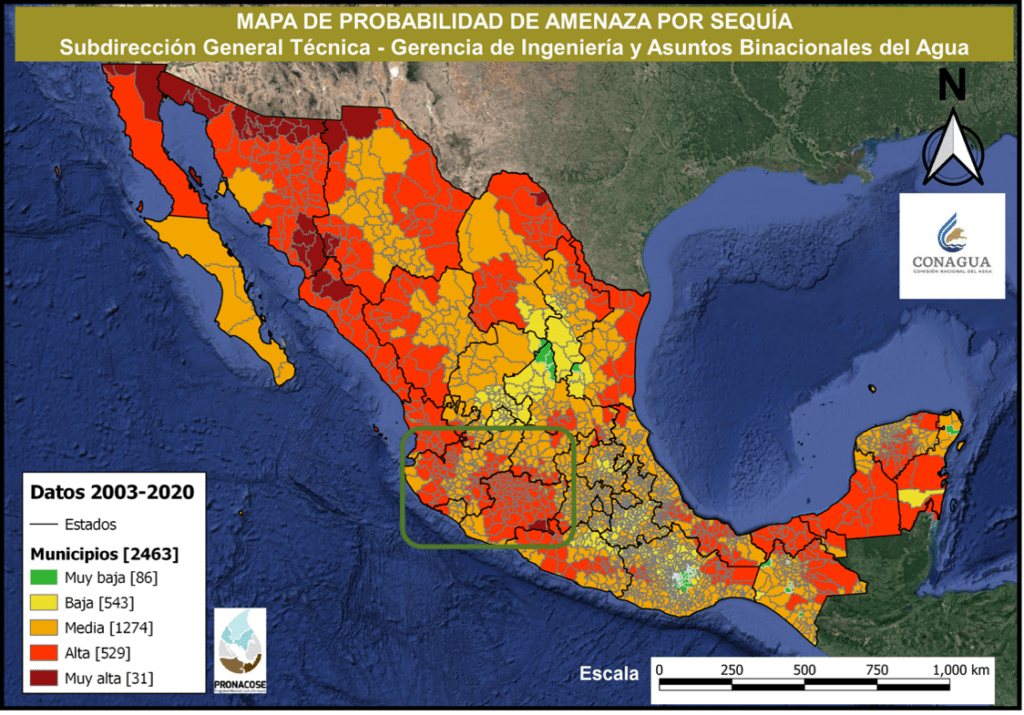

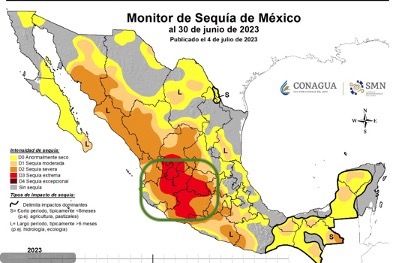

These avocado-driven pressures on water supplies are occurring in a context of water scarcity in the region. Virtually all of the avocado-producing areas of Michoacán, and most of the areas in Jalisco, overlap with watersheds or aquifers that the government has determined to have a “deficit” of water available—meaning that additional water extraction licenses cannot be sustained. Household access to water in these regions is also limited, in some areas ranging from several hours of piped water every other day to months without the service in dry seasons.

Climate Rights International found evidence that in multiple communities, avocado production has significantly undermined residents’ access to water. In some cases, it has impacted their human right to adequate water for personal and domestic use, including by limiting their ability to bathe or wash clothes. For example, in El Atascoso, Jalisco, residents said that a well dug to irrigate a nearby orchard on recently deforested land has dramatically reduced the amount of water in the springs the community relies on for household use, causing some residents to leave their homes and move elsewhere.

One resident of El Atascoso who lives alone after his family members left said that he now only has enough water to bathe once every week or two. He estimates taking just a little over 40 liters of water per day from what is left of the areas’ springs, to drink and use for bathing, washing clothes, flushing the toilet, cleaning dishes, and maintaining a farm animal. He said he cannot afford to buy water.

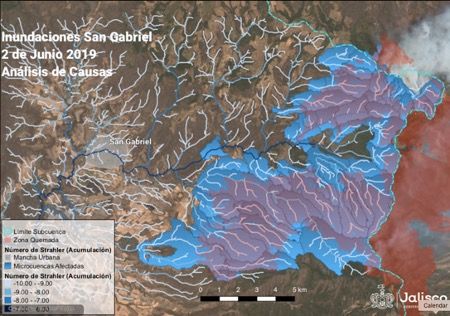

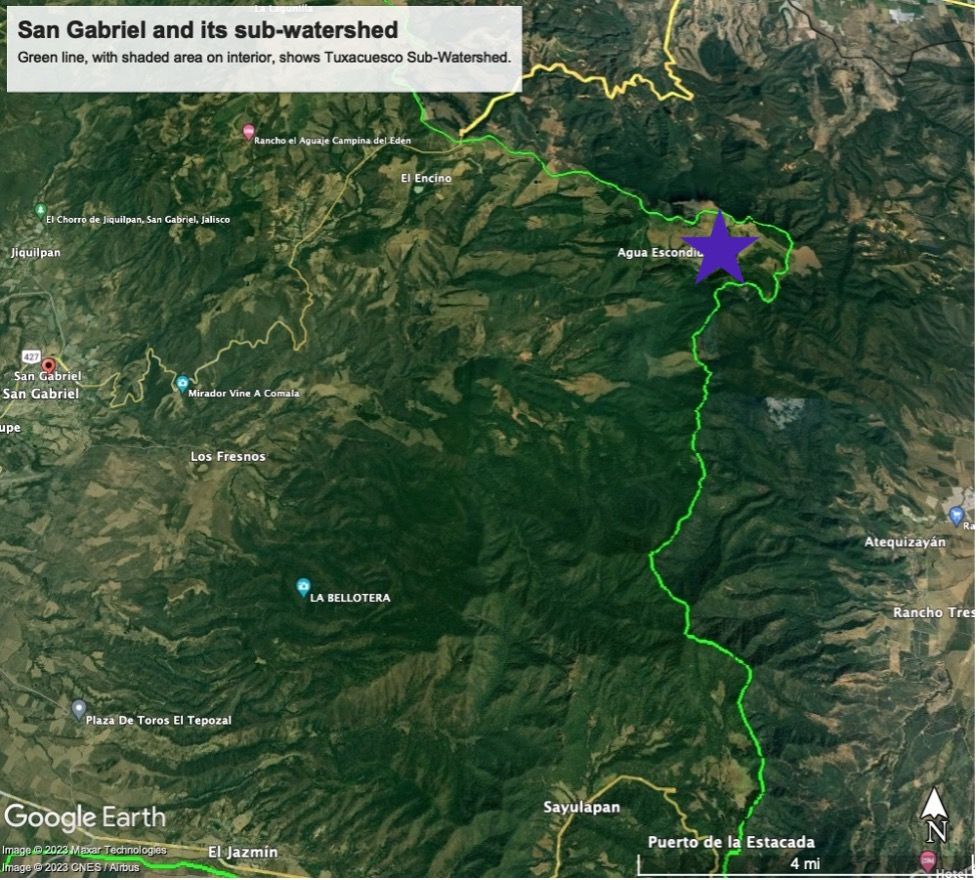

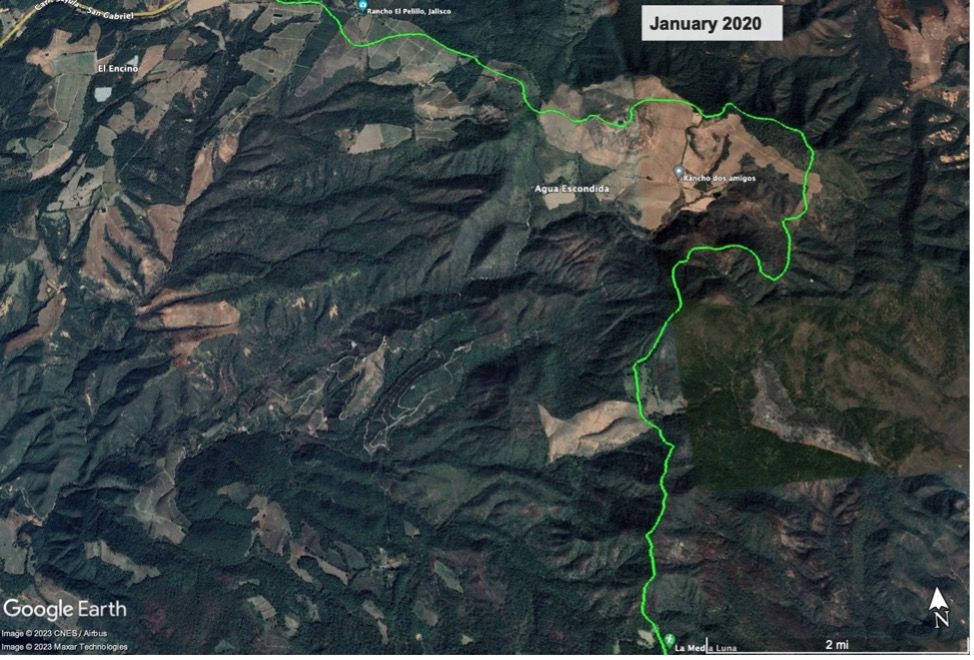

Deforestation linked to avocado production has also put local populations at risk of catastrophic floods and landslides, according to scientists and government authorities. For example, authorities investigating the causes of a 2019 flash flood in San Gabriel, Jalisco—which killed five people—identified deforestation and forest fires as central causes of the disaster. Climate Rights International found significant evidence linking avocado expansion to the forest fires and the deforestation in the area that preceded the flood.

Conserving forests from avocado expansion will help shield local populations from the foreseeable harms of climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world’s leading scientific authority on the subject, projects that global warming will increase drought and aridity in the region where Michoacán and Jalisco are located.20IPCC Working Group I, “Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis,” 2021, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-i/, p. 126 (showing for “North Central America” high confidence in increase of mean temperature, extreme heat; heavy precipitation and pluvial flood; aridity; fire weather; and medium confidence of increased agricultural drought at global warming of 2.0-2.4 degrees Celsius). The IPCC also projects that when it does rain, there will be more heavy precipitation, which increases the risk of severe flooding, and can trigger deadly landslides.

The illegal deforestation and large-scale water capture connected to avocado production are increasing the risks these climate-related harms pose to local populations. Depleted aquifers make populations less resilient to drought. And deforestation amplifies the risk of catastrophic floods and landslides.

Furthermore, the deforestation is contributing to the global climate crisis. Forests absorb climate-warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it as carbon; when trees are cut down or burned, they release the greenhouse gas back into the air. That is why more than 140 governments worldwide—including the United States and Mexico—have made climate commitments to work to end deforestation globally by 2030.21“Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use,” November 2, 2021, https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20230418175226/https://ukcop26.org/glasgow-leaders-declaration-on-forests-and-land-use/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

The conversion of forests to avocado crops reduces the capture and storage of carbon in Mexico. One scientific study recently concluded that the “need to minimize deforestation for avocado expansion is clear, as aboveground carbon storage in Michoacán’s pine-oak forests is more than double that of avocado orchards.”22Audrey Denvir, “Avocados Become a Global Commodity: Consequences for Landscapes and People,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Texas at Austin, August 2023) p. 92. The study compared carbon storage between orchards and native forests at the edge of avocado-producing areas in Michoacán, which are at high risk of conversion to orchards. The findings were similar to a previous academic study concluding that pine-oak forests had 1.7 times higher aboveground carbon content than avocado orchards. Ibid., pp. 71, 91 (citing Ordoñez et al., “Carbon content in vegetation, litter, and soil under 10 different land-use and land-cover classes in the Central Highlands of Michoacán, Mexico,” Forest Ecology and Management (2008), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2007.12.024). A 2012 study by Mexico’s National Institute for Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research (INIFAP) on the impacts of converting forests to avocado orchards, asserted, based on global academic studies, that forests capture “four to seven times more carbon than the most vigorous fruit orchards.” INIFAP, “Impact of Land-Use Change From Forest to Avocado,” p. 38. The study notes that capture rates depend on many factors, including the age of the trees, and that fruit trees are annually harvested and pruned, so that “part of the captured carbon in the end returns to the atmosphere.” Ibid., p. 37.

For more than a decade, drug cartels and other organized crime groups have maintained a powerful presence in Michoacán and Jalisco, often imposing their control through extreme acts of violence targeting anyone who gets in their way. These groups have sought to profit from avocado expansion in the two states. As documented in this report, they have links to many avocado businesses, ranging from their involvement in deforestation for orchards to owning avocado businesses and extorting those owned by others. In this context, the mere presence of armed men in avocado expansion areas can intimidate residents. These links contribute to a widespread, well-founded belief that it is dangerous to defend the environment and people’s rights from the harmful impacts of avocado businesses.

Greatly intensifying this climate of fear are the repeated threats and attacks against those who have dared to oppose deforestation and water impacts linked to avocado production. Climate Rights International documented more than 30 threats or other acts of intimidation, four abductions, and six shootings—five of which were fatal—that were associated with avocado expansion in Michoacán and Jalisco. For example, in Michoacán, Alfredo Cisneros Madrigal, an Indigenous community leader, was shot dead in February 2023, after reporting to the authorities illegal logging in an area where community members said armed people had been trying to convert forest to avocado orchards. In Jalisco, following the deadly 2019 San Gabriel flood, a state environmental official who documented the deforestation that was a central cause of the disaster began receiving phone calls threatening to kidnap them.

This fear has impeded and deterred efforts by residents and even officials to protect forests and water. For example, in Madero, Michoacán, where one activist was kidnapped in 2021 and another threatened at gunpoint in 2022, fellow environmental defenders said they limited their efforts to denounce and confront deforestation and water theft because they feared violent reprisals. In Jalisco, an experienced journalist working in an avocado-producing region told Climate Rights International that it is prohibitively dangerous to investigate and publish stories about deforestation for avocados there.

Authorities in Michoacán and Jalisco also said that the presence of organized crime and fear of violence significantly impede their ability to contain illegal deforestation and water theft. They described multiple occasions in which the presence of armed men—presumed members of organized crime—forced them to abort field operations. Officials said some avocado expansion areas are simply too dangerous for them to go to without being escorted by security forces.

Much of the avocado-growing region of Michoacán has substantial Indigenous Purépecha populations, and some of the production areas of Jalisco have Indigenous Nahua populations. According to one academic article, in 11 avocado-growing municipalities of Michoacán that constitute the “Meseta Purépecha” region, 60 percent of the population identified as Indigenous Purépecha, when excluding the region’s main urban center of Uruapan.23Alfonso De la Vega-Rivera and Leticia Merino-Pérez, “Socio-Environmental Impacts of the Avocado Boom in the Meseta Purépecha, Michoacán, Mexico,” Sustainability (2021), https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137247 (accessed July 13, 2023). Many communities have Indigenous governing authorities—called community councils—and traditional communal lands.

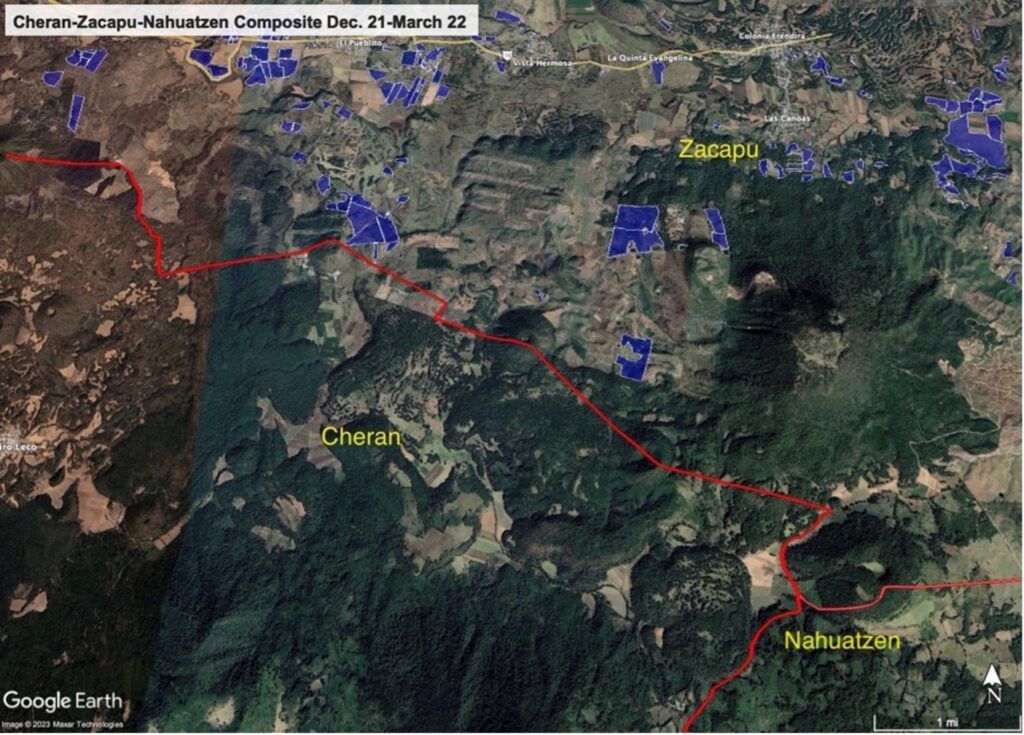

Residents of some of these communities have organized to prevent deforestation for avocado production. In Cherán, Michoacán, following years of illegal logging and violence, community members rose up in 2011 to expel municipal authorities, who they accused of corruption. They set up an autonomous government, prohibited the planting of avocado on communal lands, and established their own police force—which was subsequently authorized by the state government—to patrol and protect the forests.24CRI interviews with residents, Cherán, Michoacán, March 2, 2023. Cherán has had enormous success in protecting its forests from the expanding avocado frontier. (Satellite images in Appendix A show this success.)

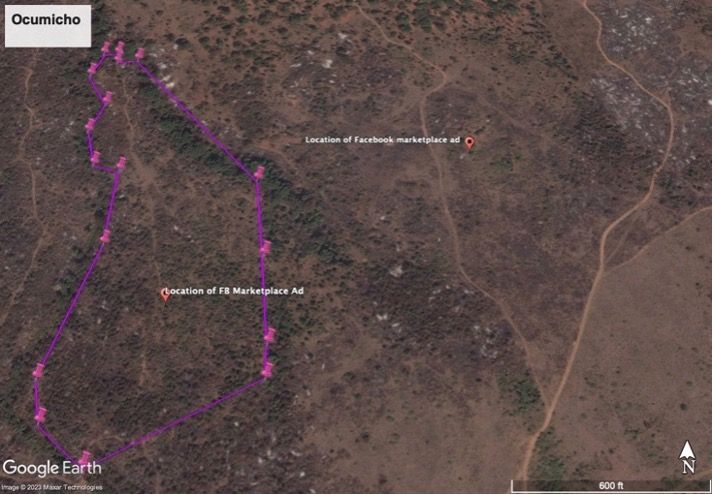

Nevertheless, the efforts of several other Indigenous communities to shield forests from avocado expansion have been severely undermined by killings, kidnappings, and threats against leaders and members. For example, since the community of Ocumicho, Michoacán issued a resolution in 2018 prohibiting outsiders from planting avocado within their community, two community leaders were shot, one fatally, and another kidnapped, and a community patrolman who had participated in efforts to stop deforestation was killed in December 2022.

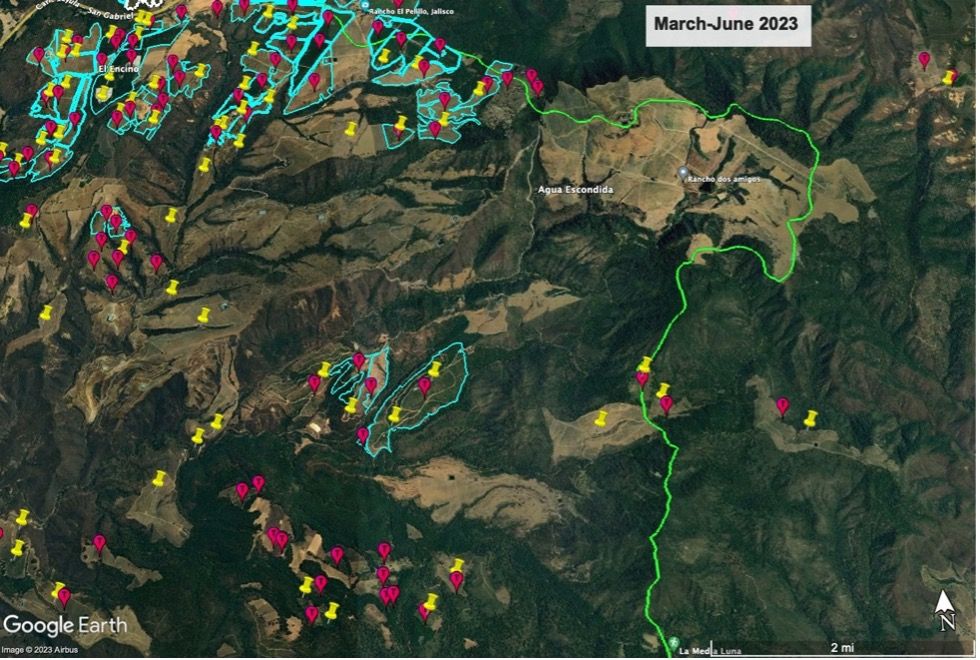

In this context, Ocumicho’s Indigenous authorities have struggled to enforce a community rule against selling or renting communal lands. Climate Rights International identified Facebook posts from 2023 advertising plots for avocado production within Ocumicho’s communal land. Trees had been cleared in each of the plots. One of them borders an orchard that also is located in an area community leaders identified as communal territory, contains deforested land, and according to government records, supplied more than 15,000 kilograms of avocados to West Pak and Mission Produce in 2022.25 Records of “harvest logs” (“bitacoras de cosecha”) provided in transparency law response from SENASICA to request number 330028323000180, June 27, 2023. The orchard number is HUE08160210404.

The U.S. and Mexican governments have a range of obligations and commitments to stop deforestation, uphold human rights, and enforce environmental laws, including:

When it comes to the avocado trade, the Mexican and U.S. governments are not meeting these obligations and commitments.

The unauthorized deforestation for avocado orchards is a federal crime enforceable in Michoacán and Jalisco. It is also a state crime in Michoacán, but not in Jalisco. The crimes are called illegal “land-use change” and are punishable by between six months and nine years of prison. As noted above, all of the deforestation for avocados in Michoacán over the past two decades, and virtually all of it Jalisco, appears to have been in violation of these laws.

Officials recognize that the perpetrators are rarely held accountable for the crimes. Michoacán’s environment secretary said the “lack of order and control has come at the cost of the forest and puts at increasing risk our biodiversity, the provision of water, and the forests in this state.”27 “Avocado: Business, Ecocide and Crime: Part 1,” UGTV Territory Reporting, Sept. 7, 2022, video clip, YouTube. In the words of the head of Michoacán’s forest commission, the violators “laugh at our impotence.”28CRI interview Rosendo Caro, General Director of Michoacán State Forest Commission, Morelia, Michoacán, December 15, 2022.

While fear of reprisals plays a major deterrent role for some officials, another important reason for this impunity is corruption, particularly in the unit of Michoacán’s State Prosecutor’s Office dedicated to investigating deforestation for avocados, according to multiple state and federal officials who spoke with Climate Rights International, as well as residents.

Illegal land-use change is also a violation of federal administrative laws protecting the environment, potentially punishable with non-prison sanctions ranging from fines and closures of orchards to the forfeiture of products, and orders to restore the affected areas. While the federal environment enforcement agency has imposed some sanctions, they have not effectively deterred or reversed the land-use changes. Climate Rights International identified several orchards that were certified for U.S. export as of January 2023 despite having been sanctioned by the federal government between 2015 and 2022 for illegal land-use change.

The federal water agency that is charged with investigating and administratively sanctioning water theft rarely does so in Michoacán and Jalisco.

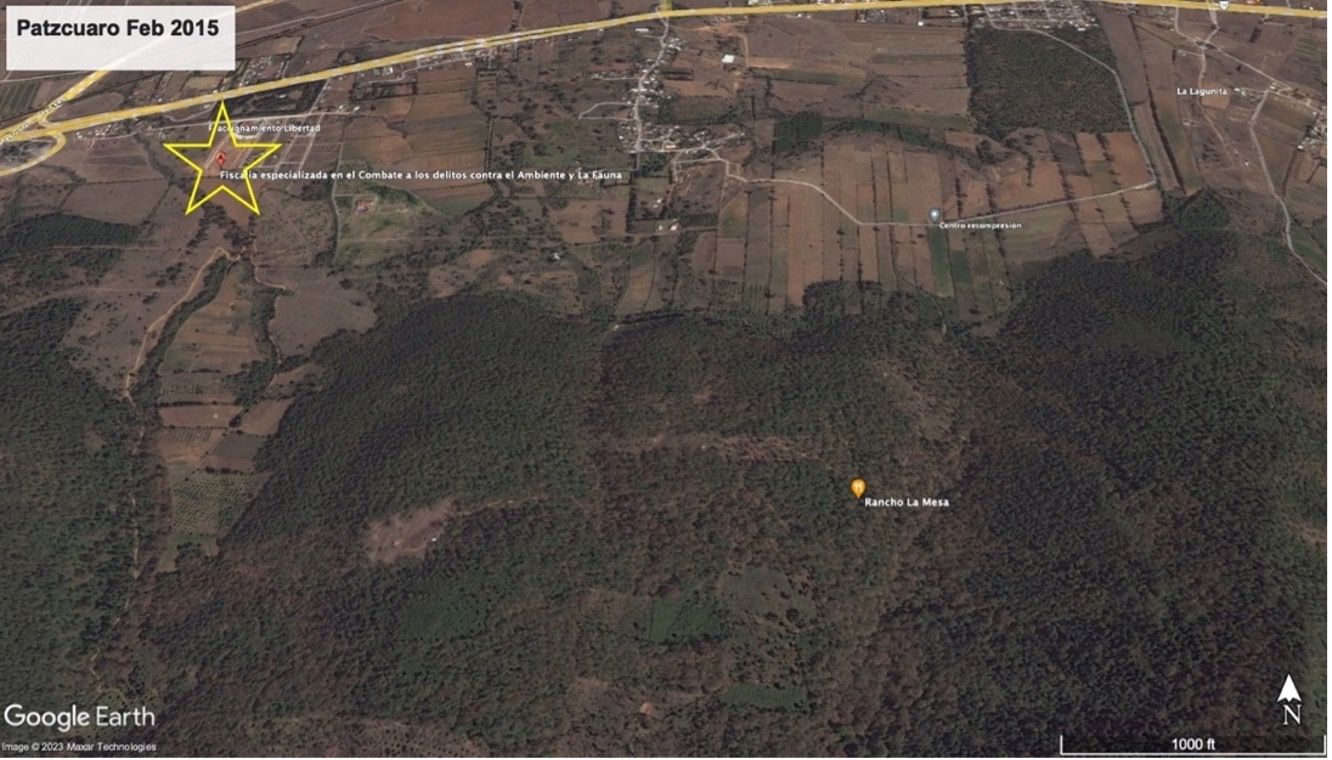

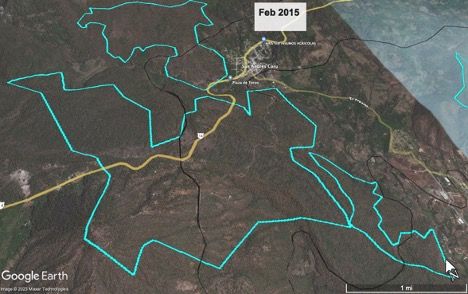

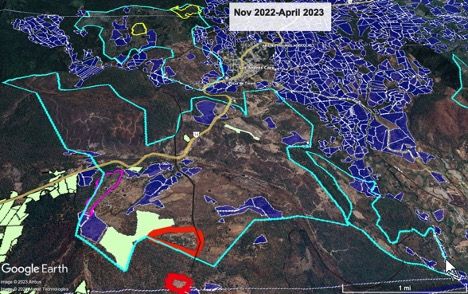

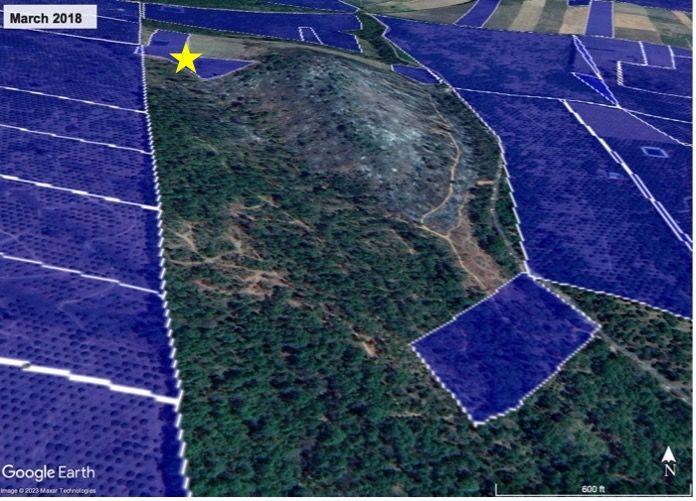

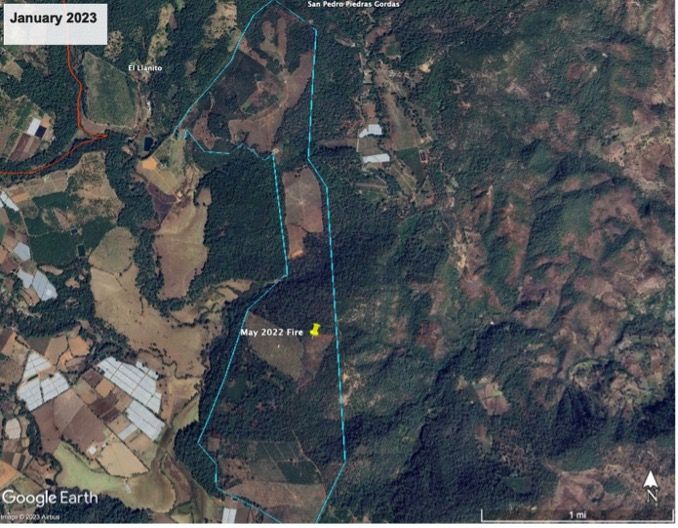

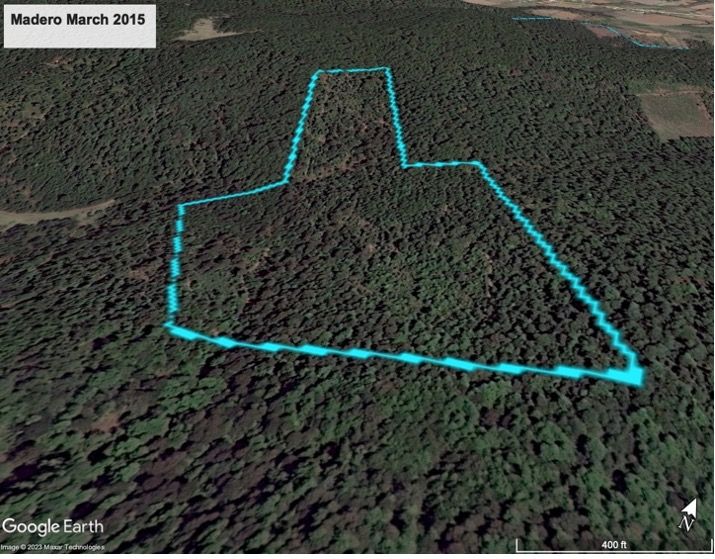

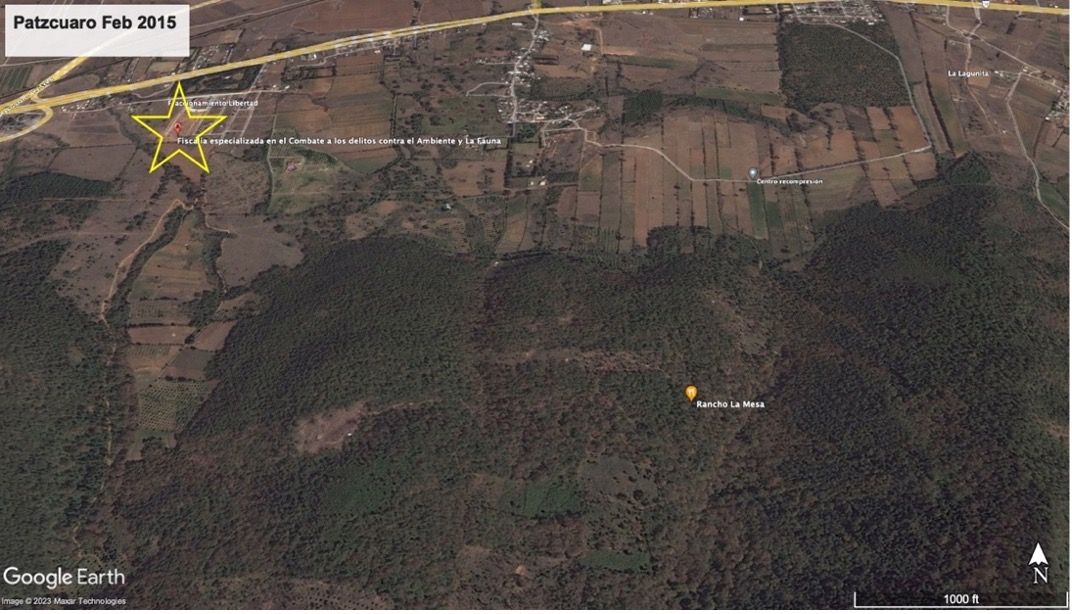

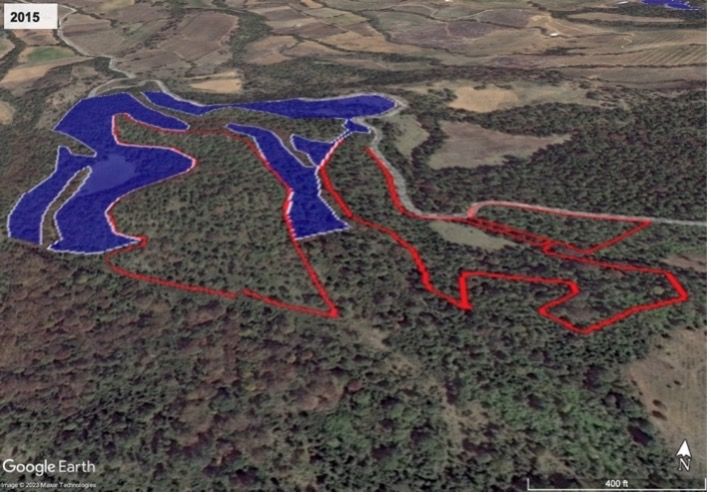

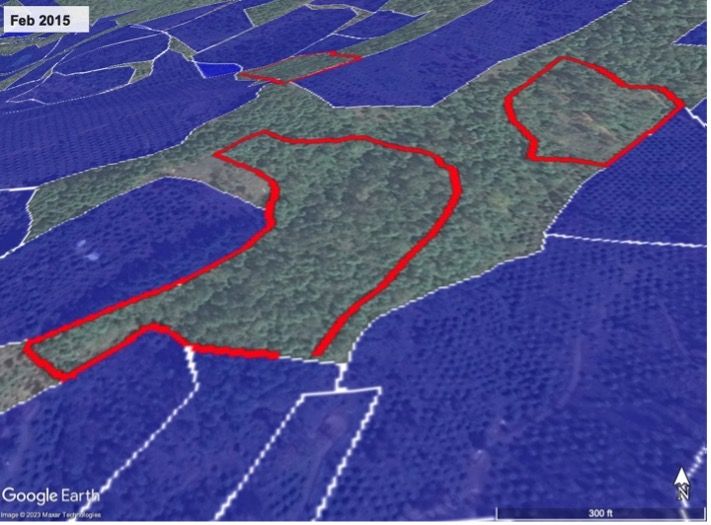

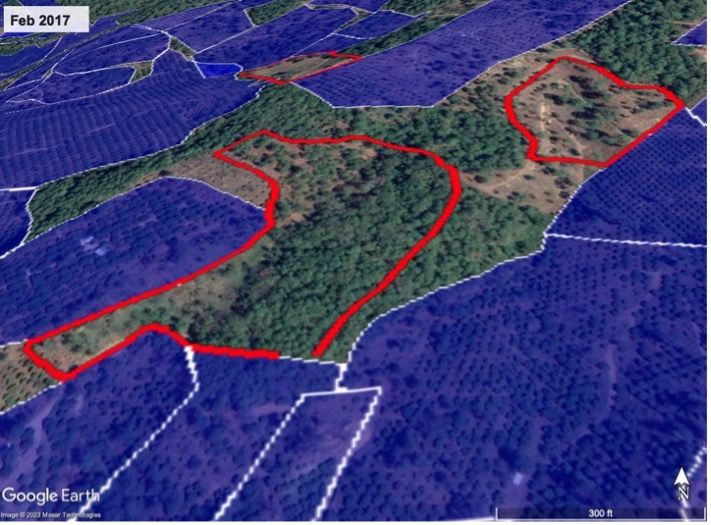

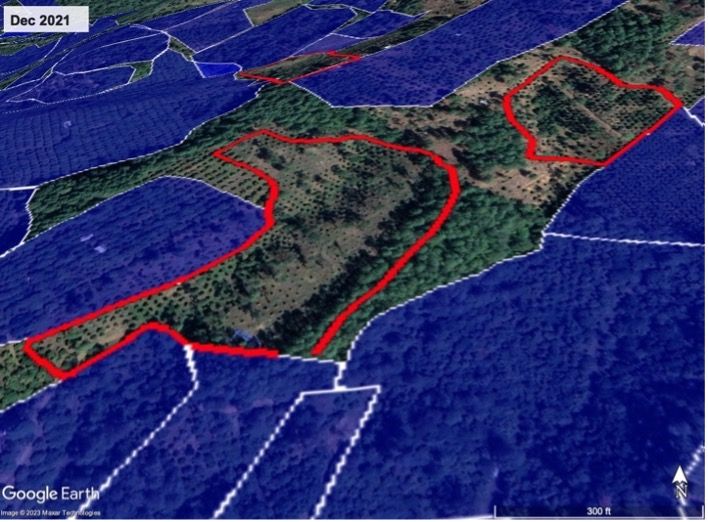

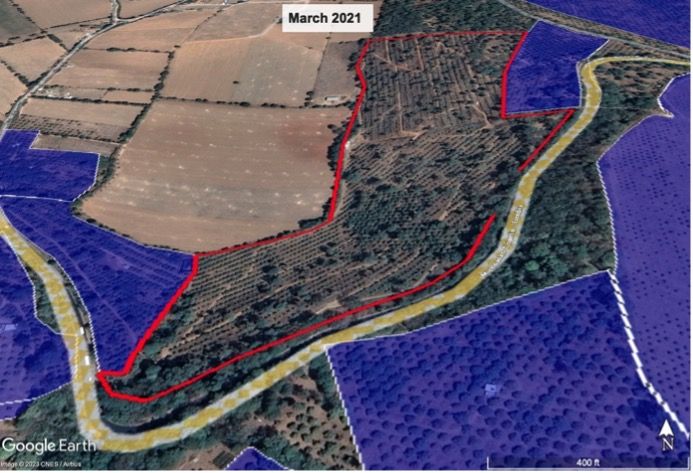

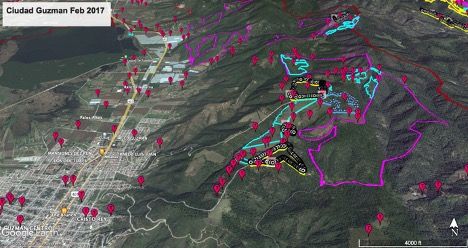

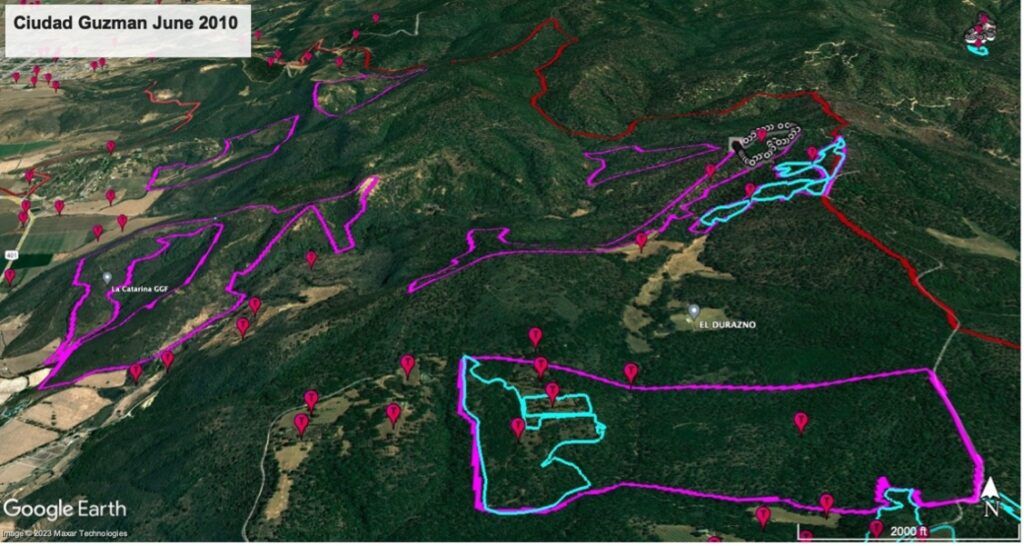

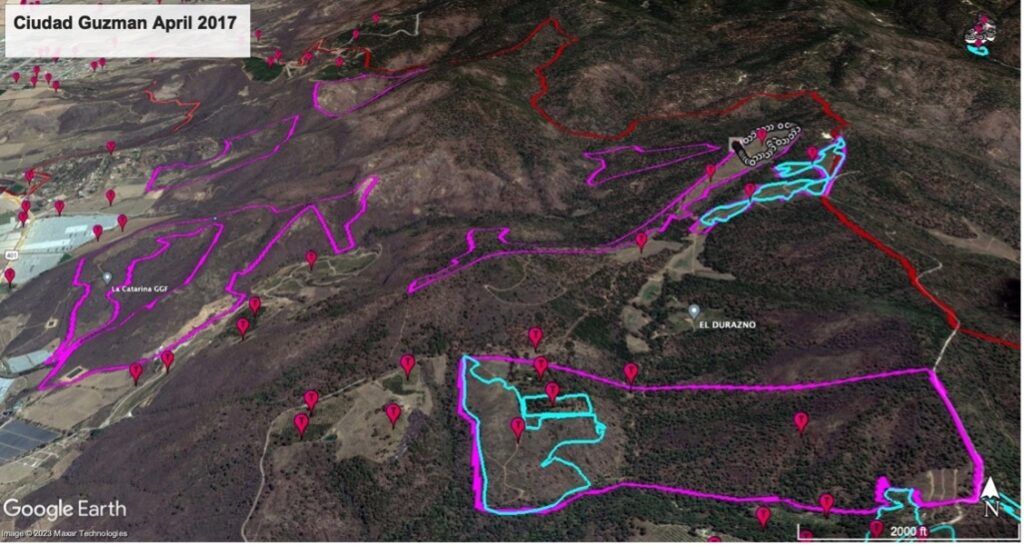

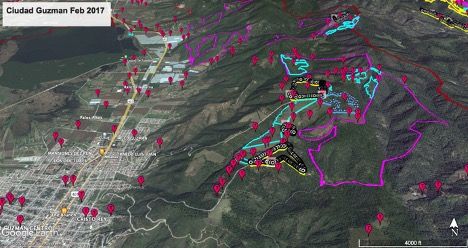

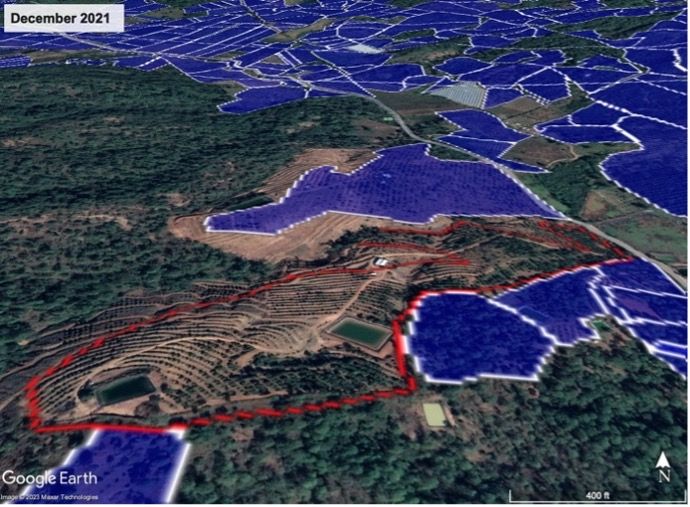

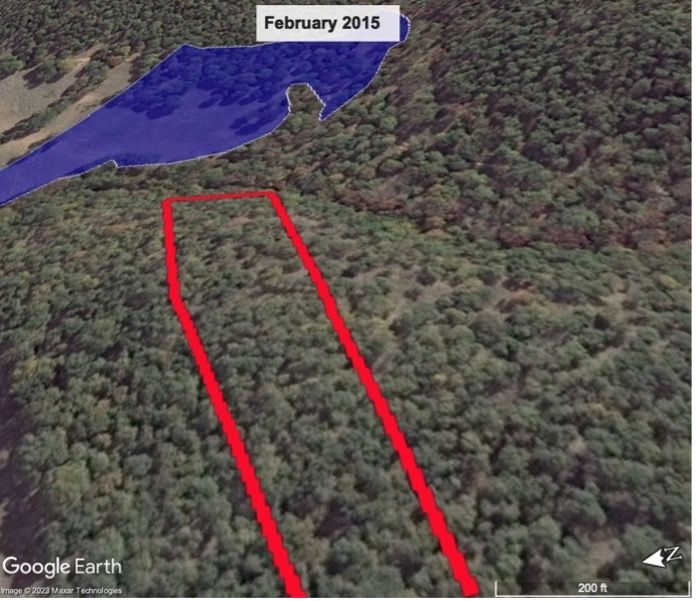

The following two Google Earth images show that avocado growers have been able to establish orchards on illegally deforested land in close proximity to Michoacán’s Specialized Prosecutor’s Office in Combatting Crimes Against the Environment and Fauna, which is charged with pursuing cases of deforestation for avocado production.29Most of the land-use change depicted in the images may have predated the establishment of the unit in 2019; however, at least part of the nearby illegal deforestation for avocado would still be obvious—and easily verifiable on Google Earth—to anyone working at the unit. CRI confirmed in a field visit—and through Google Earth imagery—that at least one of the orchards is in direct, unimpeded sight from the office.

The “before” image is a Google Earth image from February 2015. The “after” image is from May 2023. The yellow star denotes the location of the office; the purple shows deforestation sites for orchards identified by Climate Rights International; and the blue shows areas that have already been certified for U.S. export.

To its credit, the office of Michoacán’s environment secretary has promoted some potentially valuable measures to curb avocado-driven deforestation. In 2023, the agency invested in a satellite analysis tool that emits automated deforestation alerts to authorities, and has worked with experts to propose a voluntary environmental certification system for avocado growers. Yet these efforts are insufficient. For the satellite tool to make a meaningful difference, enforcement authorities would have to effectively act on the alerts—but there’s little reason to expect they will, given their poor track record in addressing flagrant illegalities. If approved, the certification system would be voluntary rather than a requirement for selling avocados to domestic or international markets, so businesses could still make money by clearing forests for orchards.

Mexico exports nearly half of its avocado production, with about 80 percent going to the United States. Between January 2019 and April 2023, Mexico exported to the United States 4.7 million metric tons of avocados, worth US$11 billion, including avocados worth US$3 billion in 2022, according to Mexican customs data compiled by the company Treid. During that period, Mexico also exported billions of dollars of avocados to Europe, Asia, and other North American countries, including US$932 million to Canada, US$708 million to Japan, US$245 million to Spain, US$172 million to the Netherlands, US$144 million to France, US$55 million to China, and US$54 million to the United Kingdom.30Mexican customs data, processed by Treid.co.

None of these countries have policies in place to prevent avocados grown on illegally deforested land from entering their markets. The United States’ lack of such a policy is particularly germane to the environmental destruction in Mexico, given its dominance of international demand. The United States’ inaction represents a failure of the Biden administration to follow through on its commitments to work to end global deforestation and promote trade policies “that do not drive deforestation,”31“Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use,” November 2, 2021. as well as to make “climate considerations” an “essential element of United States foreign policy.”32The White House, “Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad,” January 27, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/27/executive-order-on-tackling-the-climate-crisis-at-home-and-abroad/ (accessed September 12, 2023).

For a Mexican orchard to produce avocados for export to the United States, and a packinghouse to process them, each must be certified by both Mexican authorities and the USDA’s Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS). The certification criteria and process, set forth in an Operational Work Plan (OWP) signed by the two countries, seeks to prevent the spread of potential avocado pests.33SENASICA, “Operational Work Plan (OWP): Systems Approach for the Importation of Fresh Hass Avocado from Mexico into the United States,” (“Plan de Trabajo Operativo (PTO): Enfoque de Sistemas para la Importación de Aguacate Fresco Hass de México a Estados Unidos”), December 6, 2021, https://www.gob.mx/senasica/documentos/aguacate-hass?state=published (accessed July 11, 2023). The OWP does not contain any deforestation, environmental, or human rights requirements for exporting avocados.

Climate Rights International obtained documents through Mexico’s transparency law indicating that U.S. officials failed to act upon a 2021 proposal, by senior Mexican officials, to add a provision to the OWP bilateral agreement that would preclude the certification for export of orchards located on illegally deforested land. Rather than adopting this environmental protection in the OWP, U.S. authorities made a different change to the export agreement later that year: they approved Jalisco as the second state, after Michoacán, allowed to export avocados to the United States.

Records obtained through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) show that the U.S. government made the Jalisco approval without adopting measures to address the risk that, as a U.S. government report alerted at the time, it was “likely to increase deforestation” in Jalisco, as “market pressures” had done in Michoacán. U.S. authorities also ignored a 2021 letter from a Jalisco family to the United States Trade Representative (USTR) and the Ambassador to Mexico, reporting that their land had just been invaded and deforested for avocados, and warning that U.S. consumers would soon receive “large quantities of avocados from orchards whose origin and operation have criminal roots.”34Letter from Jalisco family to Ken Salazar, U.S. Ambassador to Mexico and Katherine Tai, U.S. Trade Representative, September 13, 2021 (translated by U.S. government), obtained via FOIA request from USTR. The USTR is charged with monitoring and enforcing the USMCA provision requiring that parties to the trade deal effectively enforce their environmental laws.

The FOIA records, and other credible evidence, also strongly suggest that the Jalisco approval was in exchange for U.S. potato growers gaining access to Mexican markets. This apparent quid pro quo underscores that the United States has significant discretion in its policy towards Mexican avocado exports. It also makes the U.S. approach to avocados an even more glaring example of agribusiness interests taking precedent over the environment—a global phenomenon deepening the climate crisis.

Businesses have a responsibility to respect human rights and the environment, as articulated in the UN’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct. For companies that sell avocados—ranging from packinghouses, exporters, and importers to supermarkets—these responsibilities include conducting due diligence to identify, prevent, and mitigate human rights and environmental harms in their supply chains.

Yet, Climate Rights International found strong reasons to conclude that key companies in avocado supply chains from Mexico to the rest of the world are not fulfilling their responsibility to conduct adequate due diligence to address the deforestation and other related risks.

Using government orchard maps and shipment records, we identified 75 orchards containing land that was deforested—apparently illegally—and that supplied in 2022, along with other producers, at least one of the following five major companies that exported and imported avocados from Mexico to the United States: Aztecavo,35News reports and public records suggest that Aztecavo has in recent years maintained strong corporate links to—and possibly been partially owned by—Westfalia Fruit, a multinational fruit company that claims to have “the largest avocado-growing footprint in the world.” This information is set forth in Appendix K. Westfalia officials did not respond to CRI emails about the nature of the relationship between Westfalia and Aztecavo. Calavo,36The records list “Calavo de Mexico, S.A. de C.V.” Calavo Growers, Inc.’s annual Form 10-K filing with the SEC, filed in December 2022, refers to “Calavo de Mexico S.A. de C.V” as a “wholly owned subsidiary.” Calavo Growers, Inc., Form 10-K, https://ir.calavo.com/static-files/9c13da31-3239-4843-8d91-6cff65c6bbf7 (accessed September 11, 2023). Fresh Del Monte Produce,37The records refer to “Del Monte Grupo Comercial, S.A. de. C.V.” Fresh Del Monte Produce, Inc.’s Chief Sustainability Officer confirmed to CRI that Del Monte Grupo Comercial S.A. de C.V. is a subsidiary of Fresh Del Monte Produce, Inc. Email from Hans Sauter, Fresh Del Monte Produce, Inc. Chief Sustainability Officer, to CRI personnel, September 5, 2023. A 2019 filing with the SEC also states that “Del Monte Grupo Comercial, S.A. de. C.V.” is a “subsidiary” of Fresh Del Monte Produce, Inc. Second Amended and Restated Credit Agreement, https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1047340/000119312519263746/d813314dex101.htm (accessed September 11, 2023). Mission Produce,38The records list “Mission de Mexico, S.A. de C.V.” Mission Produce, Inc.’s annual Form 10-K filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), filed December 22, 2022, lists “Mission de Mexico, S.A. de C.V.” as a “subsidiary.” Mission Produce, Inc., Form 10-K, Exhibit 21.1, https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1802974/000180297422000050/exhibit211subsidiariesofre.htm (accessed September 11, 2023). and West Pak Avocado.39The records refer to “Grupo West Pak de Mexico, S. de R.L. de C.V.” Available information strongly indicates that Grupo West Pak is a subsidiary of West Pak, even though West Pak executives did not respond to CRI emails seeking to confirm the subsidiary status. For this information, see Appendix K. Each of these companies was supplied by at least 14 such orchards; and all are U.S.-based except Aztecavo, which is a Mexican company. The 75 examples shown in this report are illustrative and not a complete accounting of the orchards containing deforested land that, according to government records, supplied the five companies in 2022; and U.S.-export certified orchards containing illegally deforested land supplied many other packinghouses in 2022 in addition to the five companies.

The four U.S. companies are vertically integrated, meaning they or their subsidiaries own packinghouses in Mexico, export abroad, and control imports within the receiving country, before distributing to retailers. According to Mexican customs data compiled by the company Treid, the companies exported the following values of avocados from Mexico to the United States between January 2019 and April 2023: US$884.6 million (Aztecavo); US$505.2 million (Calavo); US$803.4 million (Fresh Del Monte); US$1.392 billion (Mission Produce); and US$278.5 million (West Pak).

These companies—which according to government records strongly appear to have sourced a portion of their avocados in 2022 from orchards containing illegal deforestation—have in turn supplied major supermarkets, according to Climate Rights International store visits, company websites, and disclosures to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). For example, in 2023, Climate Rights International found Calavo-labeled avocados, produced in Mexico, being sold at Whole Foods, Trader Joe’s, Walmart, and stores owned by Albertsons and Kroger; and an SEC filing by Calavo reports that sales to Kroger, Trader Joe’s, and Walmart accounted for roughly 15 percent, 11 percent, and 10 percent of total net sales in 2022.40Calavo Growers, Inc., Form 10-K, https://ir.calavo.com/static-files/9c13da31-3239-4843-8d91-6cff65c6bbf7 (accessed September 11, 2023) Aztecavo’s website reports that its “end customers” include Whole Foods, Trader Joe’s, Walmart, Costco, Albertsons, Kroger, and Sprouts, among others.41Aztecavo website, “End Customers,” https://www.aztecavo.com.mx/our-final-customers (accessed September 18, 2023). In 2023, CRI also found Mission Produce-labeled avocados at Costco, and West Pak-labeled avocados at Kroger, Costco, and Target.

Beginning in April 2023, Climate Rights International sent letters to Mission Produce, Calavo, Fresh Del Monte, West Pak, and Aztecavo—and five other significant U.S.- or Netherlands-based importers—requesting detailed information about their due diligence policies and practices to address deforestation and other harms in avocado supply chains from Mexico. We also sent letters requesting such information to 11 major supermarkets with stores in the United States, Europe, and across the world: Ahold Delhaize, Albertsons, ALDI US, Amazon.com (and Whole Foods), Costco, Kroger, Lidl, Sprouts, Trader Joe’s, Target, and Walmart.

Of the 21 companies, seven responded, and only two—Walmart and Lidl—provided more than limited, boilerplate information. Just one—Lidl—provided information suggesting that it has adequate due diligence to prevent their avocado supply from Mexico from being contaminated with deforestation and other harms. Lidl stated that it requires independent certification for avocados sourced from Mexico, and referred to requirements that supply chains be deforestation free as of 2014, and that producers comply with water laws.

Most of these companies publicize—including on websites and investor reports—codes of conduct for their general global operations. These codes of conduct generally state that suppliers must comply with certain environmental and human rights requirements—including not violating environmental laws of their countries of operation—and refer to the possibility of audits. But Climate Rights International was unable to find clear publicly available information from these companies about what measures, if any, they have actually taken to audit and ensure compliance with those codes in avocado supply chains from Mexico.

The Association of Avocado Exporting Producers and Packers of Mexico (APEAM), a Michoacán-based industry group that is funded by and represents all producers and packers who export to the United States, does not conduct due diligence to address deforestation or water theft. APEAM told Climate Rights International that it does not have any polices or practices in place to:

The widespread illegal deforestation among U.S.-export certified orchards and apparent contamination of supply chains of key companies such as Calavo and Mission Produce in 2022—combined with the apparent lack of due diligence by importers, exporters, and supermarkets, and admitted lack of due diligence by APEAM—create a high likelihood that a portion of avocados from Mexico sold at supermarkets were grown on illegally deforested land.

The avocado industry has made numerous false and misleading sustainability claims, while simultaneously failing to conduct due diligence that would give consumers any confidence that the avocados they buy are free of environmental or human rights harms. For example:

Mexico, the United States, the European Union, and other countries that produce, export, and/or import avocados should adopt laws and regulations to preclude access to the marketplace for avocados produced as the result of serious violations of environmental or human rights standards.

These laws and regulations should require that companies conduct transparent due diligence to ensure they are not sourcing avocados from orchards containing recently deforested land. Companies should be required to identify, prevent, and mitigate other environmental harms and human rights violations in their supply chains.

Companies should be required to provide or cooperate in effective remediation for affected persons and communities if they have caused or contributed to deforestation or human rights violations. The remediation should include funding for impacted communities’ efforts to conserve forests and restore damaged ecosystems, and compensation for human rights violations.

Companies should be required to establish mechanisms to receive, investigate, and address complaints of abuses such as violence or intimidation against local residents or unlicensed water capture.

Companies in global avocado supply chains should voluntarily adopt the full range of due diligence and remediation policies outlined above, even in the absence of laws and regulations requiring them.

The cut-off year for what constitutes “recently” deforested land that would trigger exclusions from purchases and trade should be established in consultation with relevant stakeholders, including civil society and impacted communities. A possible cut-off date would be 2014, the year Mexico, the United States, and many other countries signed the New York Declaration on Forests, in which they committed to ending natural forest loss. The 2014 cut-off has been considered by Michoacán authorities for a possible voluntary certification scheme. Another possibility related to North American markets would be 2020, when the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement’s provisions requiring parties to effectively enforce environmental laws entered into force. For the European Union, the cut-off date could also be 2020, in accordance with the EU Deforestation Regulation, which applies to deforestation that has occurred after December 31, 2020. (The regulation does not currently cover avocados, but they should be added at the earliest possible date.)

Regulators and companies should rely on orchard maps and satellite imagery where available to verify the absence of recent deforestation.

A full set of recommendations can be found at the end of this report. Specific key recommendations include:

The Government of Mexico Should:

The Government of the United States Should:

Avocado Packers, Exporters, Importers, and APEAM Should:

Supermarkets Should:

Between December 2022 and June 2023, Climate Rights International conducted seven research trips to the states of Michoacán and Jalisco, including visits to the state capitals of Morelia and Guadalajara, as well as 13 other municipalities in Michoacán, and three more in Jalisco. Climate Rights International conducted interviews with nearly 200 people in these locations and in Mexico City, and by telephone or videocalls, including with 110 residents and activists; 48 Mexican officials at the federal, state, and local levels; 16 academics with expertise in forestry, hydrology, and environmental geography, among other areas; 12 avocado producers or industry representatives; three officials from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal & Plant Inspection Service; and seven international NGO workers. No compensation or other incentives were offered to interviewees.

We submitted more than 85 information requests to government agencies under Mexico’s Federal Law of Transparency and Access to Public Government Information (“transparency law”) and received substantive responses to most of those requests. We also submitted Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to six U.S. government agencies and received substantive responses from three. Climate Rights International also reviewed numerous scholarly, media, and government reports.

There are references throughout the report to government maps of avocado orchards in Michoacán and Jalisco certified by U.S. and Mexican authorities to export to the United States. These previously unpublished polygon maps of orchards were provided to Climate Rights International on January 23, 2023, by Mexico’s National Service of Health, Food Safety and Quality (SENASICA), in response to transparency law request 330028323000032. Climate Rights International analyzed the maps (provided in KMZ and KML format) on Google Earth Pro, which allows the viewer to review sequences of satellite images of the same pieces of land over time, and thus detect deforestation within the polygon maps of orchards. For the vast majority of polygons of orchards in Michoacán, an official orchard registration number was provided, beginning with HUE0816.

The report also has many examples of export-certified orchards containing deforested land that, according to government shipping records, supplied major packinghouses, importers, and exporters in 2022. These previously unpublished records are called “Harvest Registration forms” (Bitácora de Cosecha, BICO), and they were provided by SENASICA in June 2023 in response to transparency law request number 330028323000180. BICO records accompany each shipment of avocados from an orchard to a packinghouse that is ultimately destined for U.S. export. Climate Rights International obtained the BICO records for Michoacán orchards. The BICO record lists the official registration number of the orchard of origin (beginning with HUE0816 for Michoacán orchards) and the packinghouse destination. By comparing the registration numbers associated with the polygon maps of export-certified orchards with the registration numbers in BICO records of shipments, Climate Rights International identified instances of orchards with illegally deforested land that supplied major companies in 2022.

The Google Earth images in the report are from the providers Airbus, Maxar Technologies, CNES, and Landsat/Copernicus.

Throughout the report, identifying details are withheld for many interviewees and individuals, including withholding names and specific dates and locations of interviews, either because requested or when CRI believed publishing the information could put them at risk. We use the pronoun “they” in several parts of the report to refer to an individual without revealing their gender.

In 2016, a man with a plot of land in Zacapu received a call from a friend alerting him that there were people cutting down his trees and that they were going to take over his land for avocado production.48CRI interview with Javier (pseudonym), Michoacán, 2023 (name, location, exact date withheld). The man, called Javier here as a pseudonym, immediately went to his land (he does not live there) and saw men clearing trees with chainsaws and heavy machinery.

Javier, who spoke with Climate Rights International on the condition of anonymity, recounted subsequently learning that the land had been sold by third parties, without his knowledge, to individuals he believes are linked to organized crime. Neighboring plots of land had also been taken over and deforested for avocado production. One neighbor told Climate Rights International that, around 2017, when he tried to accompany judicial police to inspect the deforested lands, they ran into men with rifles who told them they could not enter.49CRI interview with resident, Michoacán, 2023 (name, location, exact date withheld).

The hills of Zacapu, where Javier’s land is located, have been the site of repeated forest fires. On April 6, 2017, following one such fire, the then-secretary of environment of Michoacán reportedly announced:

The avocado growers who started this fire should not get too excited, we’re not going to let this go with impunity, we’re going to do everything so that this natural disaster does not remain in impunity.50“The Ambition of a Few Won’t be Allowed to Finish Off the Forests,” (“No se premitirá que ambiciones de unos cuantos acaben con bosques”), Quadratín, April 6, 2017, https://www.quadratin.com.mx/sucesos/se-permitira-ambiciones-unos-cuantos-acaben-bosques/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

News articles, apparently based on an official press release, reported that the fire burned for three days, and that firefighters were initially prevented from reaching the fire. They were only able to put it out when public security forces intervened to enable them to gain access to it.51Ibid.; “Environmental Security Working Group: Zacapu Is Not Alone, The Ambition of a Few Won’t be Allowed to Finish Off the Forests,” (“Mesa de Seguridad Ambiental: Zacapu no está solo, no se va a permitir que ambciones de unas personas acaben con los bosques”), Mexico Ambiental, April 8, 2017, https://www.mexicoambiental.com/mesa-seguridad-ambiental-zacapu-esta-se-va-a-permitir-ambiciones-unas-personas-acaben-los-bosques/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

A local radio journalist who reported on fires in Zacapu, as well as on deforestation and coercion to sell land for avocado, was threatened.52CRI interview with journalist, Michoacán, 2023 (name, location, exact date withheld). At first, she received threatening calls at her radio station, telling her to stop “screwing around” with these issues. When she continued, she received another. The voice on the line called her a “bitch,” and said she would put out the fires “with your ass.” Two days later, she received the same message in a written note placed on her car. After that threat, the head of the radio station told her not to report on such issues because it put everyone who worked there at risk.

In September 2019, Adolfo Perez Diaz, the co-president of an association of property owners in the area where Javier’s land is located, was shot dead in Zacapu.53CRI interviews with residents, Michoacán, 2023 (names, locations, exact dates withheld). United Mexican States, Death Certificate, Adolfo Perez Diaz, September 18, 2019. Paciano Anguiano, who also had a leadership role in the association of property owners, was killed in the same attack.54CRI interviews with residents, Michoacán, 2023 (names, locations, exact dates withheld); United Mexican States, Death Certificate, Paciano Anguiano Garcia, September 19, 2019. One community member told Climate Rights International that, prior to being killed, Perez had told him he was threatened in relation to the takeover of land for avocados.55CRI interviews with residents, Michoacán, 2023 (names, locations, exact dates withheld).

Around the same year as the killings, Javier filed a complaint with the prosecutor’s office stating that, after visiting his land and seeing it being fenced off, he received a phone call telling him he would be killed if he returned again.56Complaint filed with Michoacán State Prosecutor’s Office, 2019 (exact date and case number withheld). The complaint states that 15 men had been clearing his land with the intention to plant avocado. In 2020, he filed another complaint stating that he had again tried to visit his land and been threatened by men there.57Complaint filed with Michoacán State Prosecutor’s Office, 2020 (exact date and case number withheld).

In June 2021, Javier and his neighbors delivered a letter addressed to the then governor-elect of Michoacán, listing the names of 20 people and communities whose property had been “taken over” and “logged” by people who “threaten that if you want to fight for your land you have to come up against armed people, in what are now avocado orchards.”58Letter addressed to then-Michoacán Governor-Elect Alfredo Ramírez Bedolla, June 18, 2021. Javier said the letter was delivered. The letter requests investigations, help recovering lands, and to “freeze the accounts of the armed ones and their allies in crime,” who “threaten that our lives are worth very little compared to what they’ve taken from us.”

Javier said that in 2022, when he visited his land to take photographs, a truck rushed at him, leading him to run and hide in a nearby avocado orchard.

Others also described acts of armed intimidation and a climate of fear surrounding the deforestation for avocados in Zacapu. A member of the Indigenous forest guard of Cherán, Michoacán said that, when patrolling the outer limits of Cherán that borders Zacapu, he has seen workers in Zacapu avocado orchards armed with rifles.59 CRI interview with member of Indigenous forest guard, Cherán, Michoacán, March 2, 2023. One local environmental activist in Zacapu told Climate Rights International that they would be afraid to denounce deforestation for avocado production because of the presence of armed men in the areas of the land-use change. Another said they had been warned by an official not to cause trouble for the people deforesting the hills of Zacapu because these people were linked to organized crime and could “disappear you.”60CRI interview with resident, Michoacán, 2023 (name, location, and exact date withheld).

Meanwhile, the government has not fulfilled the promise by the environment secretary, in 2017, to ensure accountability for the “avocado growers who started” the April 2017 fire. Avocado orchards were subsequently installed in the same location as the fire he denounced, according to satellite imagery and heat points detected by Mexico’s Fire Alert System.61See Appendix B. These orchards are in an area where large tracts of deforested land have been certified for export to the United States. While they themselves have not yet been certified, there is nothing to prevent them from obtaining certification, like the vast majority of Michoacán orchards.

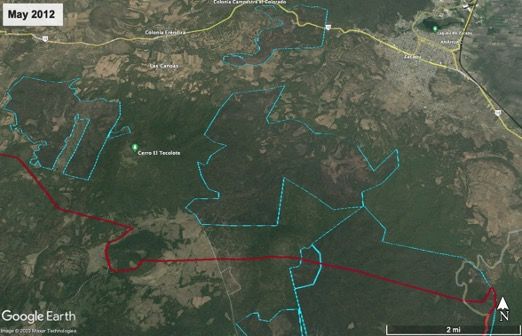

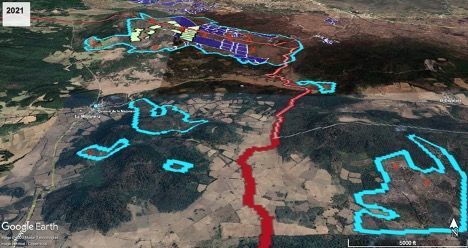

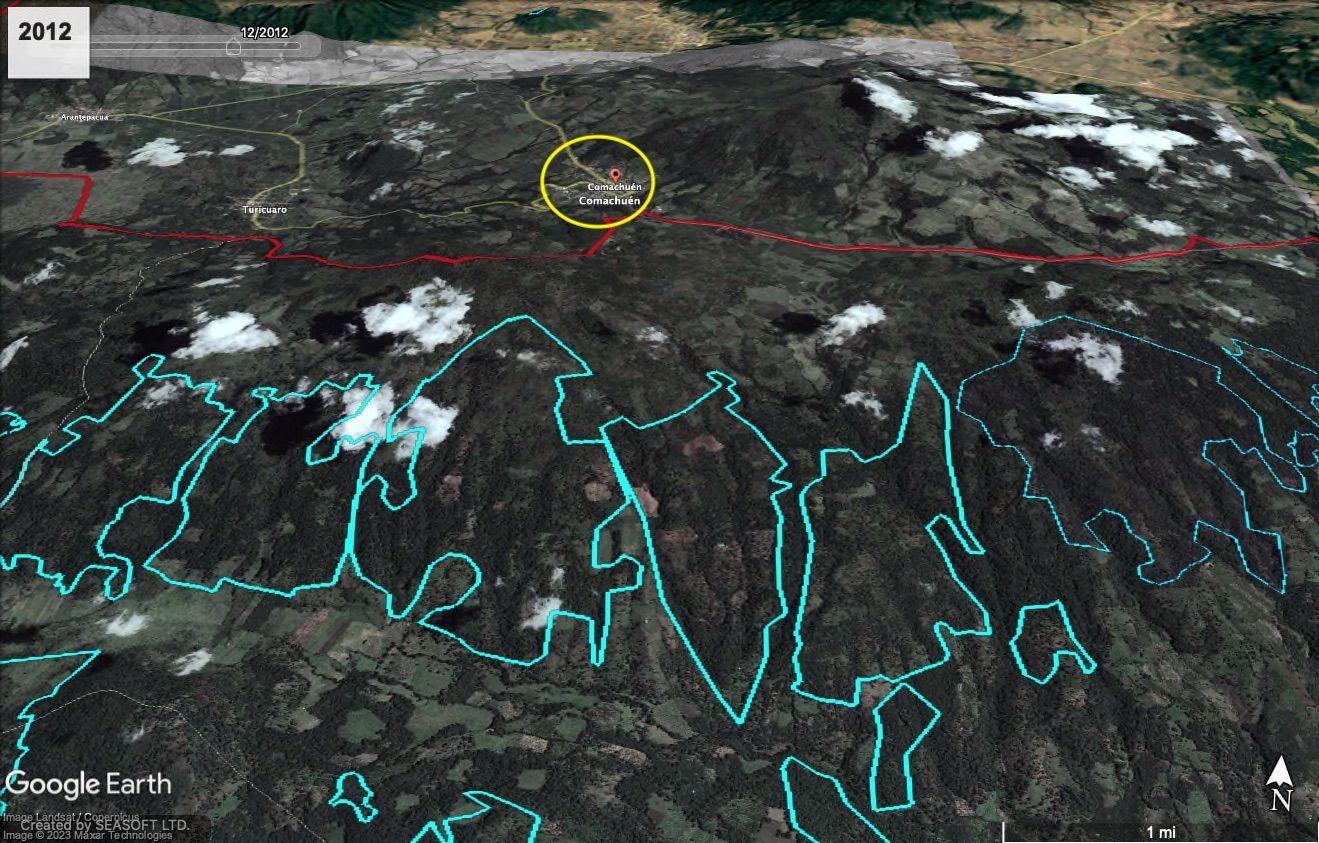

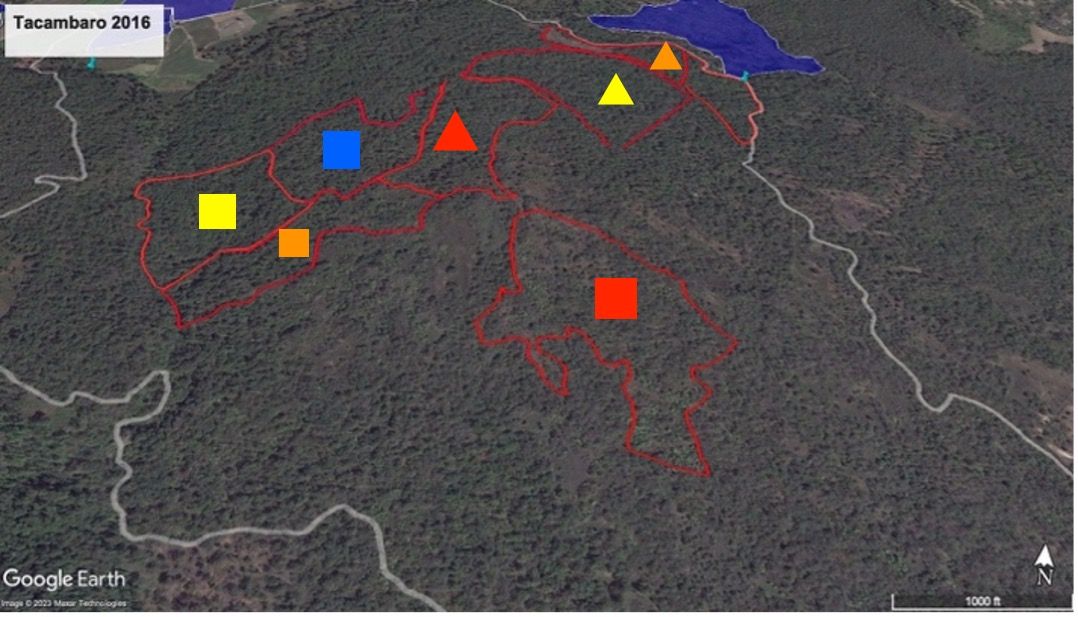

The following Google Earth satellite images show large-scale deforestation in Zacapu for avocado orchards, including many that have already been certified to export to U.S. consumers.

These two Google Earth satellite images are from 2012 (“before”) and a composite of 2021-2023 (“after”). Everything above the red line is an area of Zacapu municipality. The light blue line delineates focal points of deforestation identified by Climate Rights International, though the entirety of the area within the light-blue outlines—here and in images below—is not necessarily deforested.

This is the same image as the 2021-2023 composite directly above, but with dark blue and green polygons showing U.S.-export approved orchards as of January 2023,62Polygons of export orchards provided in transparency law response from SENASICA to request number 330028323000032, January 23, 2023. many of which are in deforested areas.

These two Google Earth satellite images show a different area of Zacapu from 2012 (“before”) and a composite of 2021-2022 (“after”). Everything to the right and below the red line is Zacapu.

This is the same image as the one directly above, but with dark blue polygons showing U.S.-export approved orchards as of January 2023.

Townspeople of Patuán told Climate Rights International that they cried as they watched the forested Cobrero Hill that towers over their village go up in flames.63CRI interviews with residents and officials, Patuán, Michoacán, January 25, 2023 (names withheld). Over the previous five years, they had observed, powerlessly, as armed men in trucks drove through town, day and night, with the wood they had illegally logged from the hill. They had been warned by a leader of an organized crime group not to interfere with the plundering of wood from the hill, where avocado orchards had been expanding. But the scale of the fire that started on April 30, 2022, devouring Cobrero Hill, sparked the community to organize.64Ibid.

With state and federal firefighters occupied fighting fires in neighboring Uruapan—including one officially classified by the Forest Commission of Michoacán (COFOM) as intentionally started for land-use change—65Transparency law response from COFOM to request number 160336023000002, February 7, 2023. (Data for fires 22-16-0456 and 22-16-0457.) Patuán residents took matters into their own hands: they climbed up the hill to start combatting the fire themselves. The residents, and firefighters who later arrived, observed that when they suppressed the fire in one location, it moved to another part of the hill, leading residents and officials to conclude that the fire was being intentionally.66CRI interviews with residents and officials, Patuán, Michoacán, January 25, 2023; CRI telephone interview with forest-sector official in Michoacán, February 10, 2023 (name withheld).

A resident told Climate Rights International:

It hurt our souls because we love this hill. We grew up here and it meant a lot to us. They set it completely on fire to the point that we couldn’t do anything…. The goal was land-use change, to plant avocados.67CRI interview with resident, Patuán, Michoacán (name and date withheld).

All told, the fires burned 284 acres of trees and 1,946 acres of shrubs and vegetation, according to government figures.68Transparency law response from COFOM to request number 160336023000002. (Data for fire 22-16-0459). Michoacán’s Secretary of Environment stated: “It’s presumed that the hill was burned by people who wanted to change the land use, remove the forest to put—more than anything else—avocado orchards, which is what there is in that area.”69“The Town That Said Enough! Resisting Illegal Land-Use Change,” (“El pueblo que dijo basta! Resistir al cambio ilegal de uso de suelo”), Sept. 10, 2022, video clip, Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/SistemaMichoacano/videos/654609972756042/?extid=NS-UNK-UNK-UNK-IOS_GK0T-GK1C (accessed July 11, 2023). Another environmental official told Climate Rights International: “Obviously they start the fire looking [to plant] avocado. That was the origin of the fire.”70CRI telephone interview with environmental official, February 10, 2023 (name withheld).

After the fire, residents set up a 24-hour checkpoint at the entrance to town, to review entering trucks for avocado plants and tools related to avocado production.71 CRI interviews with residents and officials, Patuán, Michoacán, January 25, 2023 (names withheld). Children marched in the streets opposing deforestation, chanting “not one more pine!”72“In Defense of the Cobrero,” (“En defensa del Cobrero”), May 16, 2022, video clip, Facebook, https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=684514915991155&id=100007548521364&sfnsn=scwspwa&mibextid=RUbZ1f (accessed July 11, 2023).

The community checkpoint lasted three months. Two weeks after it ended, trucks started entering the area with avocado plants. Residents and officials told Climate Rights International that avocado has subsequently been planted in parts of the area of the fire.73CRI interviews with residents and officials, Patuán, Michoacán, January 25, 2023 (names withheld).

Local authorities said that the fire, right before the start of the rainy season, increased the risk of flooding and landslides for Patuán.

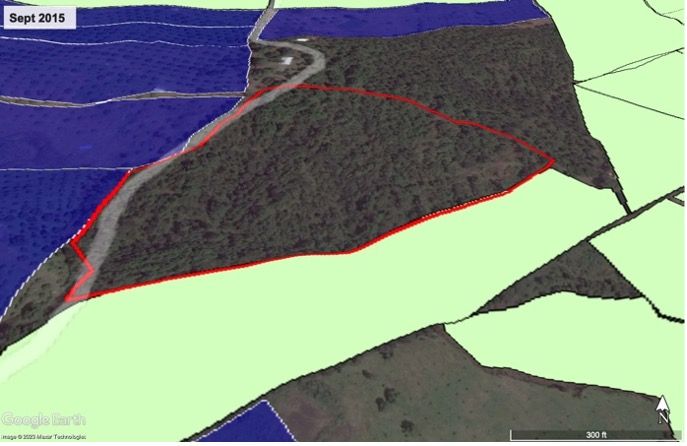

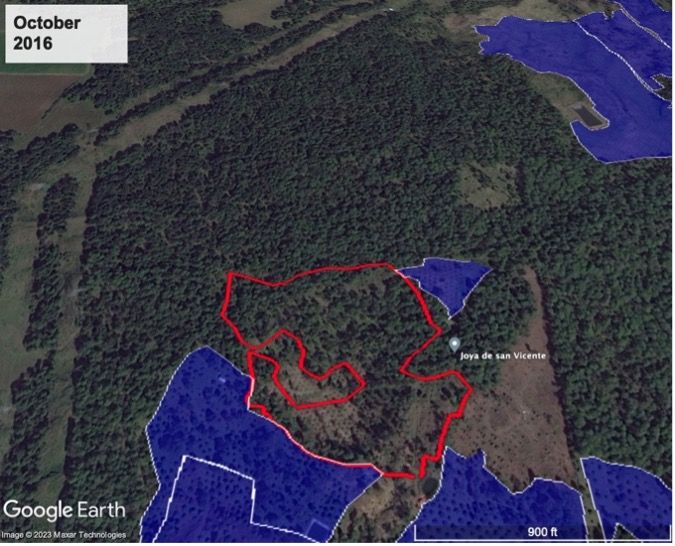

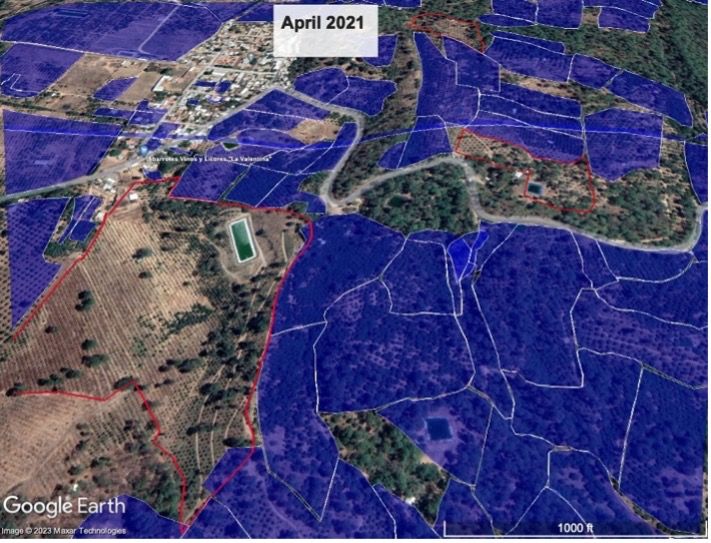

The following Google Earth image shows that the area of the fire is at the southwest frontier of a major avocado-export production zone.74See Appendix C, for images showing the clearing of trees on Cobrero Hill and growth of avocado orchards there since 2015, including after the 2022 fire.

Google Earth image from December 2021; green polygon is area of fire according to government data,75Polygon of fire downloaded from CONAFOR and National Council for Science and Technology (CONACYT), “Forest Fire Danger Prediction System of Mexico,” http://forestales.ujed.mx/incendios2/ (accessed September 12, 2023). The data shows historical “conglomerations” of “forest heat points” detected by satellite. blue polygons are U.S.-export approved orchards.76Polygons of export orchards provided in transparency law response from SENASICA to request number 330028323000032, January 23, 2023. Patuán is below the red triangle.

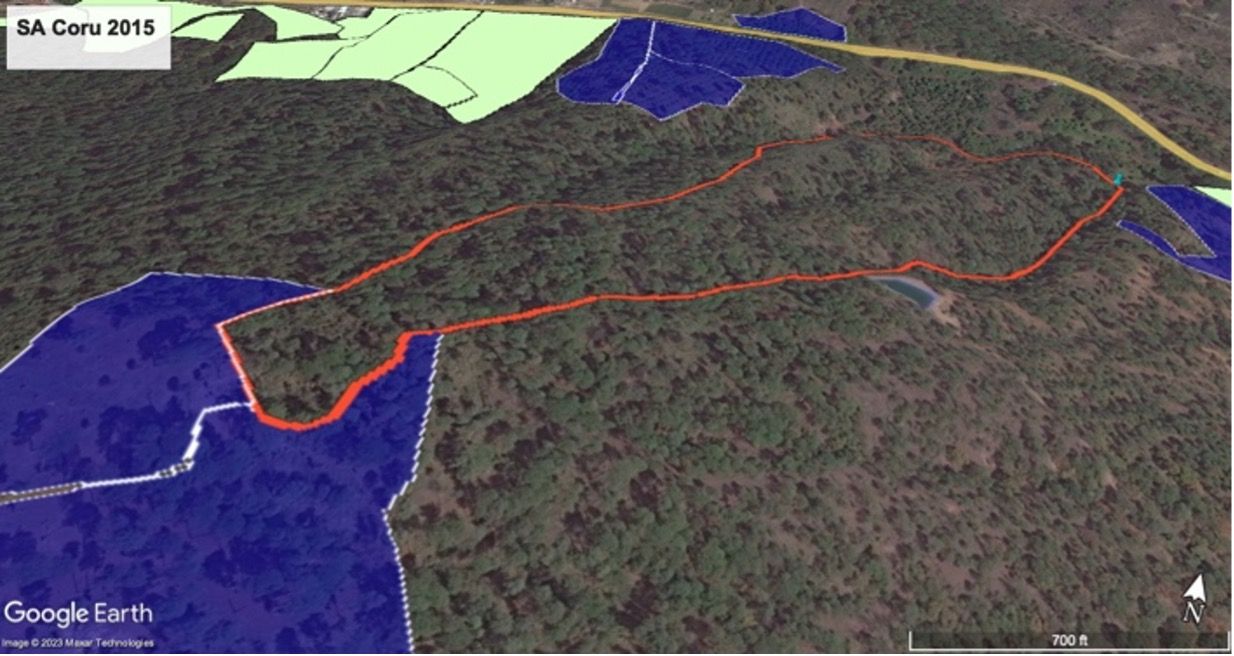

In addition to Patuán, the hills near the village of San Andrés Coru is another area in the municipality of Ziracuaretiro where there has been significant deforestation and expansion of avocado orchards in recent years. Climate Rights International received credible first-hand testimony that, like in the Patuán area, armed men have participated in the illegal deforestation there, and organized crime has been involved.77CRI interview with resident, 2023 (name, location and exact date withheld).

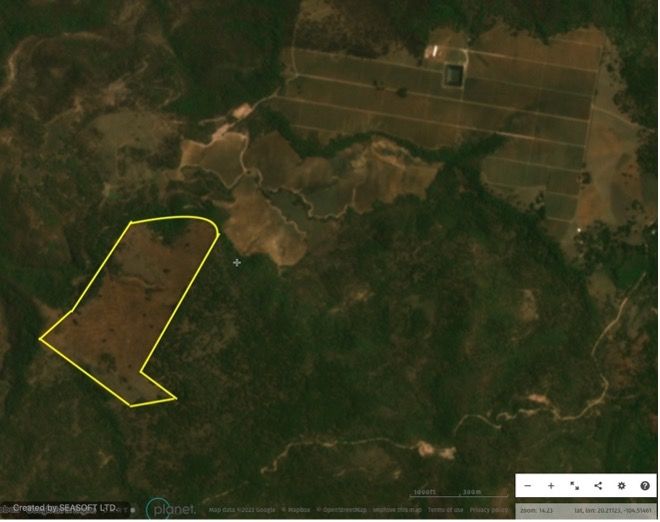

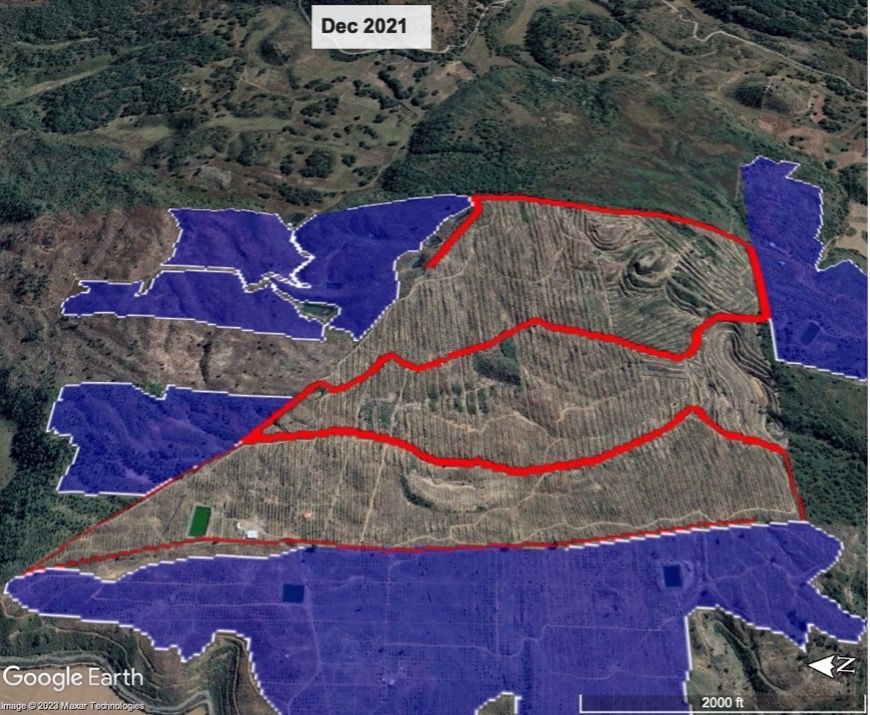

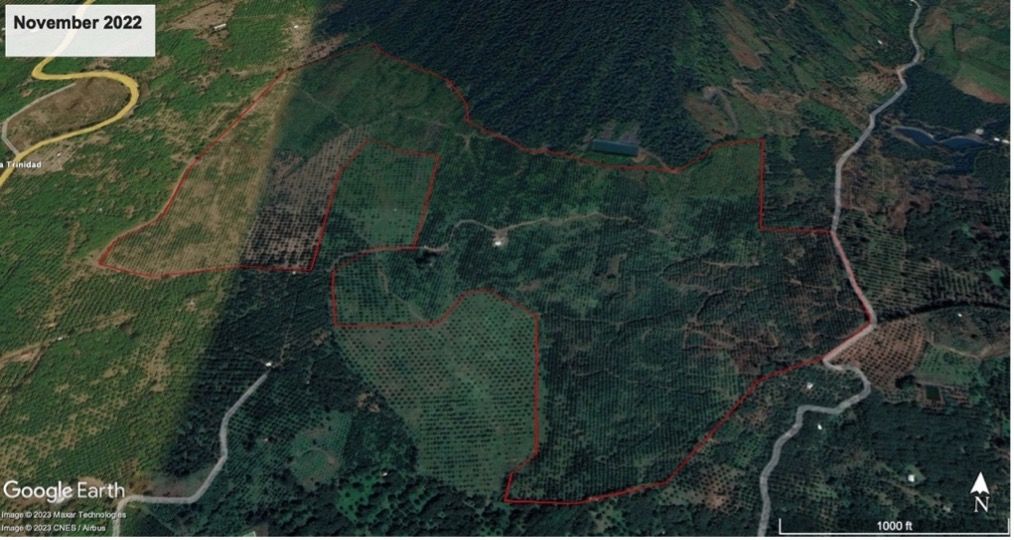

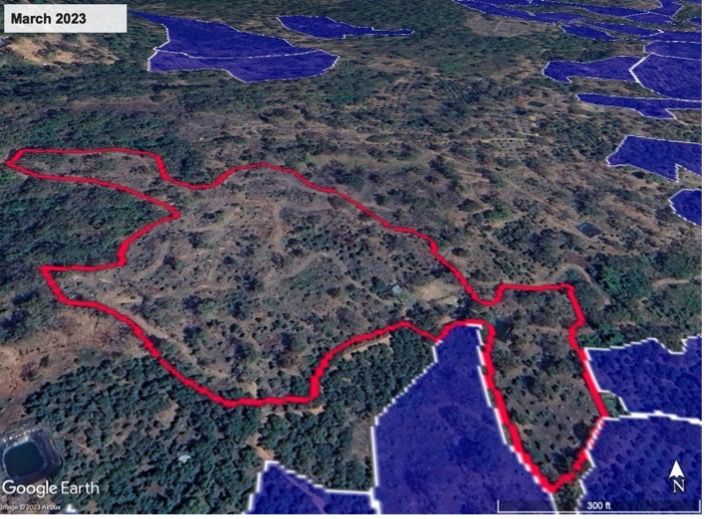

The following satellite images show extensive deforestation for avocado orchards near San Andrés Coru. Notably, San Andrés Coru is located just outside of Uruapan, Michoacán’s second biggest city, where APEAM is headquartered and many major international fruit companies have packinghouses. The yellow line running right through the middle of the deforestation around San Andrés Coru is Federal Highway 14, which goes from Uruapan to Michoacán’s capital of Morelia.

The “before” image is a Google Earth image from February 2015. Light blue outlines are general areas of deforestation after February 2015 identified by CRI, though the entirety of the area within the light-blue outlines has not necessarily been deforested. The three areas contain 3,596 acres.

The “after” image is a Google Earth satellite image of same area, with a composite of images from April 2023 and in top left corner November 2022—the most recent available dates for areas shown.

Google Earth satellite image from November 2022 and April 2023. Blue and green polygons are U.S.-export approved orchards. Government shipment records indicate that in 2022:

Zoom in on preceding Google Earth satellite image, showing example of the grid of avocado plantings outside of blue and green polygons, and pink-outlined orchard. These—and other areas within the light blue outline, and outside the export-polygons—are at risk of being approved for export to the United States.

Google Earth satellite image, with the latest available images, composite from April 2023 (left side) and December 2021 (right side). The image shows the proximity between the city of Uruapan—the second biggest city in Michoacán, where APEAM is headquartered and many major fruit companies have packinghouses—and the light blue-outlined deforested area for avocados around San Andrés Coru, and the green polygon showing the area of the fire on Cobrero Hill.

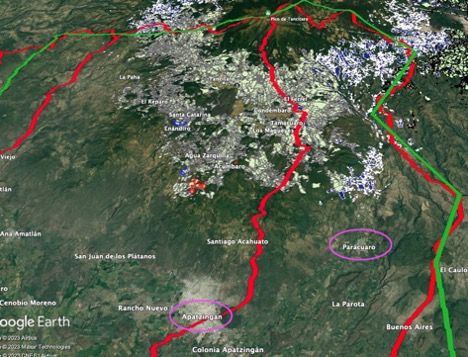

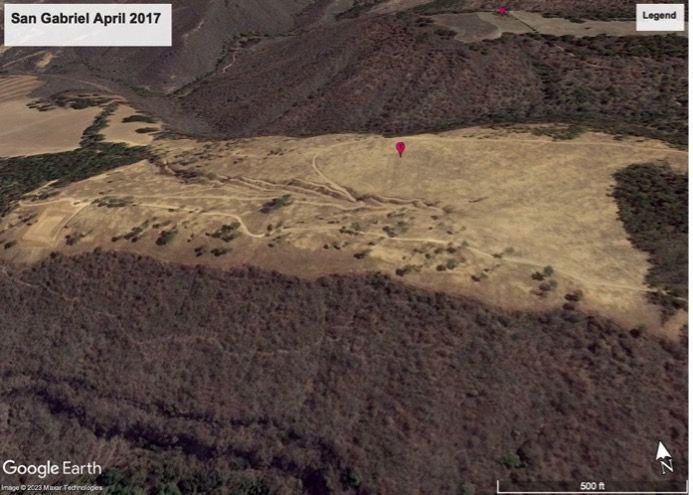

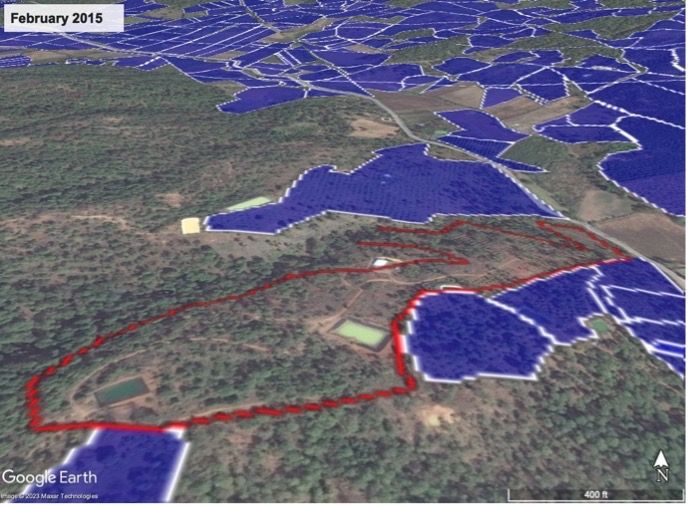

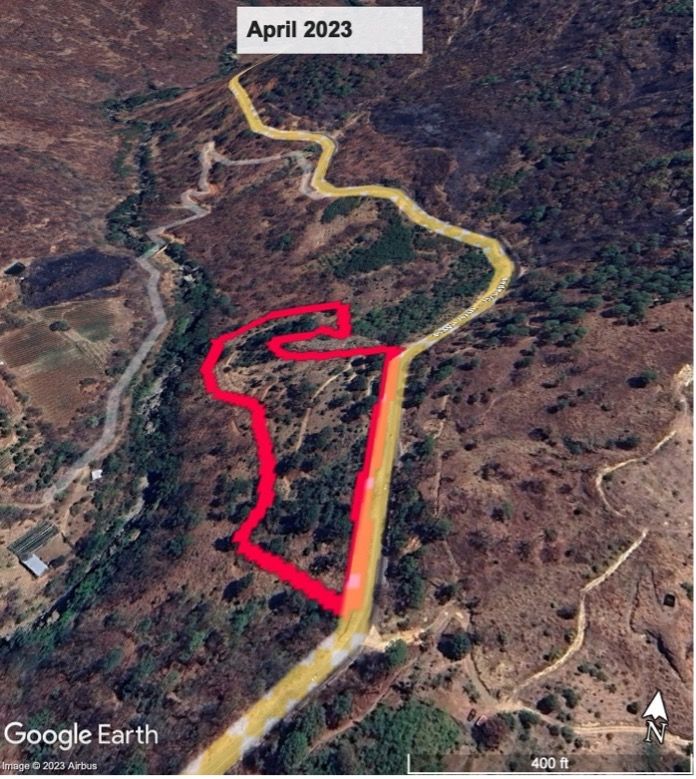

San Gabriel is a municipality in southern Jalisco where the expansion of avocado production has caused deforestation and forest fires, depleted water supplies, and—evidence strongly suggests—contributed to a deadly flash flood in 2019.

The region is dominated by the Jalisco Cartel New Generation (CJNG). In 2015, in a town that is just a 2.5 hour drive from San Gabriel, the CJNG shot down a military helicopter with rocket-propelled grenades.81José de Córdoba, “Mexican Army Helicopter Was Shot Down With Rocket-Propelled Grenades,” The Wall Street Journal, May 4, 2015, https://www.wsj.com/articles/mexican-army-helicopter-was-shot-down-with-rocket-propelled-grenades-1430783784 (accessed July 11, 2023). In December 2022, the CJNG kidnapped and killed an army colonel in a community just north of San Gabriel.82Pablo Ferri, “Colonel José Isidro Grimaldo Killed in Jalisco, the Second Attack Against a Military Commander in Last Month,” (“Asesinado en Jalisco el coronel José Isidro Grimaldo, el Segundo atentado contra un mando military en el ultimo mes”), https://elpais.com/mexico/2022-12-15/asesinado-en-jalisco-el-coronel-jose-isidro-grimaldo-el-segundo-atentado-contra-un-mando-militar-en-el-ultimo-mes.html (accessed July 11, 2023).

One resident described the situation in San Gabriel as that of “narco peace” (paz narca)—a lack of violent conflict due to the hegemonic control of the cartel.83CRI interview with resident, San Gabriel, Jalisco, 2023 (name and exact date withheld). Others described armed CJNG members openly passing by and greeting local and state police.84CRI interviews with residents, Jalisco, 2023 (names and exact dates and locations withheld).

The municipal seat of San Gabriel sits in a valley. The mountains above it, in the same sub-watershed, have undergone significant deforestation for avocado orchards over at least the past 15 years. In May 2019, forest fires in those mountains spread across at least 12,350 acres, according to authorities.85National Center for Disaster Prevention (CENAPRED), “Socioeconomic Impact of the Principal Disasters that Occurred in Mexico,” (“Impacto Socioeconómico de los principals desastres ocurridos en México”), June 2021, https://www.cenapred.unam.mx/es/Publicaciones/archivos/457-IMPACTO_SOCIOECONOMICO_2019.PDF, p. 41 (accessed July 11, 2023); complaint filed by Jalisco Secretary of Environment and Territorial Development and other authorities with the PROFEPA, February 28, 2022, p. 3, obtained through transparency law in response by Jalisco Government’s Coordination of Territorial Management to request number 142042123004861, April 18, 2023. One person who was an official at the time of the fires told Climate Rights International that individuals flying over the fires in a helicopter could see people intentionally igniting them, and that the fires were presumably for avocado.86CRI interview with person who was an official at the time of the May 2019 fires, 2023 (name, location, and exact date withheld).

On June 2, 2019, following intense rain, the Salsipuedes River, which passes through the town of San Gabriel, overflowed, flooding the streets with a powerful torrent of water, rocks, mud, and burnt tree trunks that swept up cars and damaged homes, businesses, schools, and infrastructure. Five people were killed.87Complaint filed by Jalisco Secretary of Environment and Territorial Development and other authorities with the PROFEPA, February 28, 2022, pp. 2-4; Gloria Reza, “Jalisco: Devastating Land-Use Change,” (“Jalisco: Devastador cambio de uso de suelo”), Proceso, https://depredadores.proceso.mx/jalisco.html (accessed July 11, 2023).

As discussed in detail in chapter 3, authorities investigating the reasons for the flash flood identified the May 2019 forest fires and deforestation as central causes, and Climate Rights International found evidence linking avocado expansion to those fires and the deforestation in the area that preceded the disaster.

Following the June 2019 flood in San Gabriel, efforts to address the deforestation were met with threats. For example, a person who was an official from Jalisco’s SEMADET at the time of the disaster said that they started receiving telephone threats after contributing to an internal report about the flood, which had their name on it.88CRI interview with victim of threat, Jalisco, 2023 (name and exact date and location withheld). The callers told them not to “stick their nose where it did not belong,” and threatened to kidnap them. Meanwhile, some local environmental defenders began to meet less frequently and be less outspoken due to fear of violent reprisals.