View of a Kingfisher project drilling rig next to Lake Albert. © Mathieu Ajar

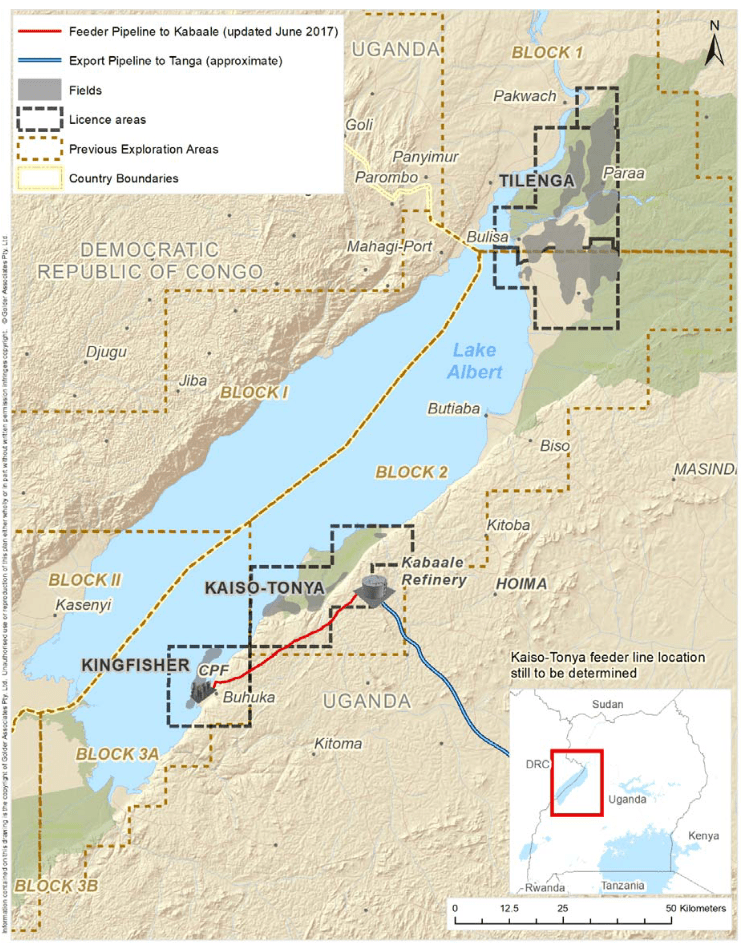

Kingfisher and Tilenga oil development projects and planned pipeline.1TotalEnergies website, https://totalenergies.com/projects/oil/tilenga-and-eacop-projects-acting-transparently

“I was not happy and didn’t want to sign at the beginning. But [CNOOC] told me that if I didn’t sign, the land would be taken.” – Joseph Mugisha from the village of Nzunsu B2Climate Rights International interview with Joseph Mugisha. Due to the high level of repression in the Kingfisher area and fears of retaliation by the Uganda Peoples’ Defence Force, private companies, private security forces, oil and gas police, or regular police, pseudonyms have been used for all interviewees.

“When you ask them [soldiers] who is in charge, they say CNOOC.” – Resident living near a Ugandan military camp in the Buhuka Flats3Climate Rights International interview.

“When I had my boat, life was okay. I could have some goats, ducks, chickens. But now I have nothing. I can’t afford the expenses for my children, including school fees. Before, I had two or three meals, but now I struggle to have one meal per day. Sometimes I don’t have any meals, like yesterday. In one month, I can spend ten days without food.” – Francis Okoth from the village of Kyabasambu, who had his boat confiscated by the Ugandan military4Climate Rights International interview with Francis Okoth.

“[That’s] my oil. I won’t allow anybody to play around with it.” – Uganda President Yoweri Museveni5Alon Mwesigwa, “Uganda determined not to let expected oil cash trickle away,” The Guardian, Jan. 13, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/jan/13/uganda-oil-production-yoweri-museveni-agriculture.

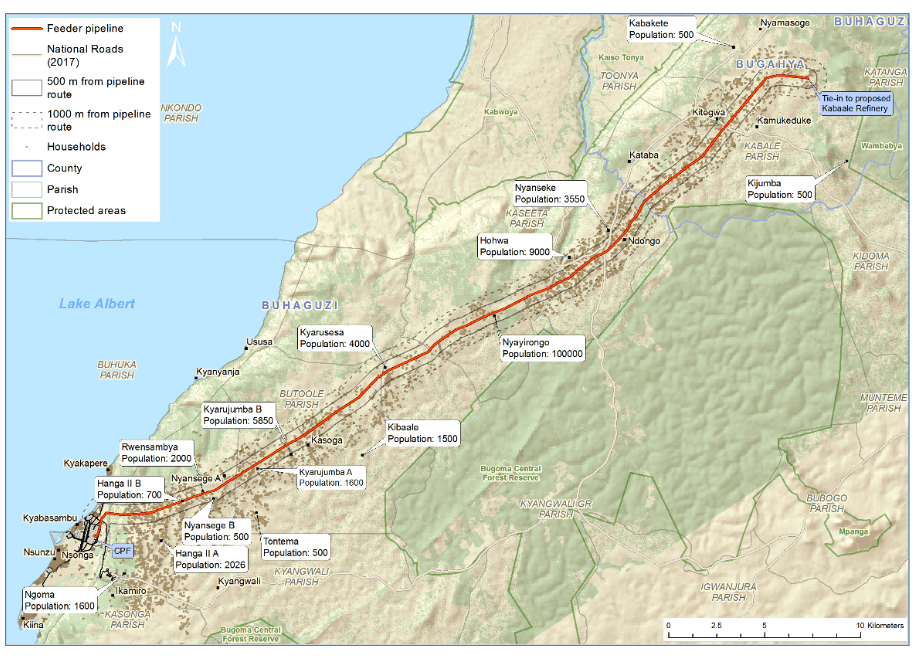

Location of the three government-designated oil license areas along Lake Albert.6CNOOC Uganda Limited, ESIA Report, Volume 1, Appendix 2, September 2018. p.4 (10) https://www.eia.nl/projectdocumenten/00006427.pdf#page=10.

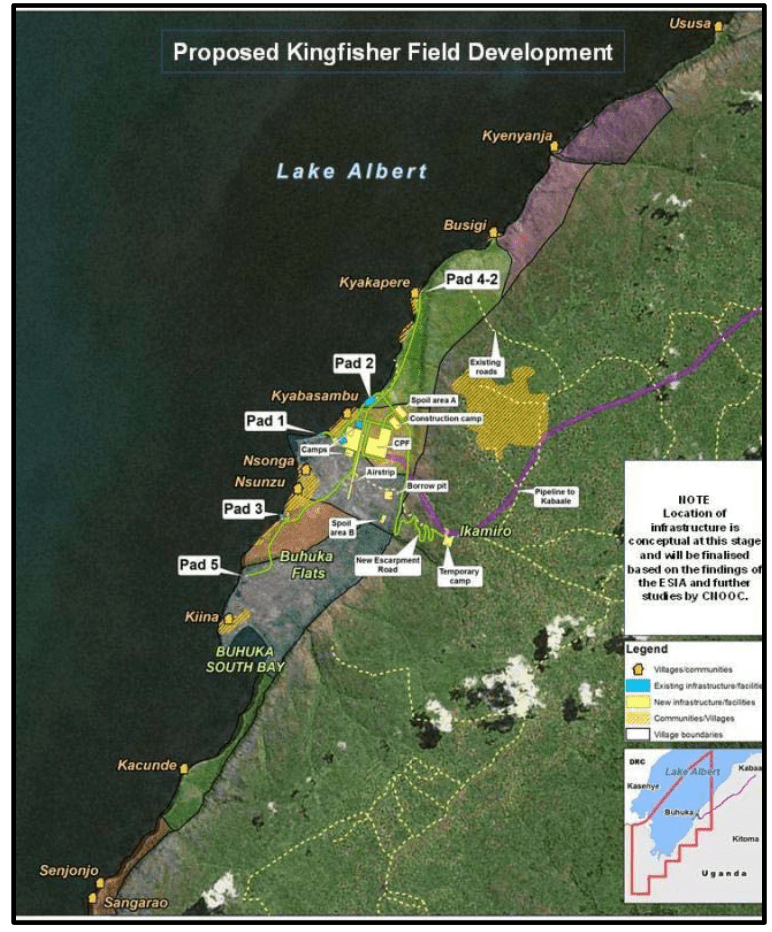

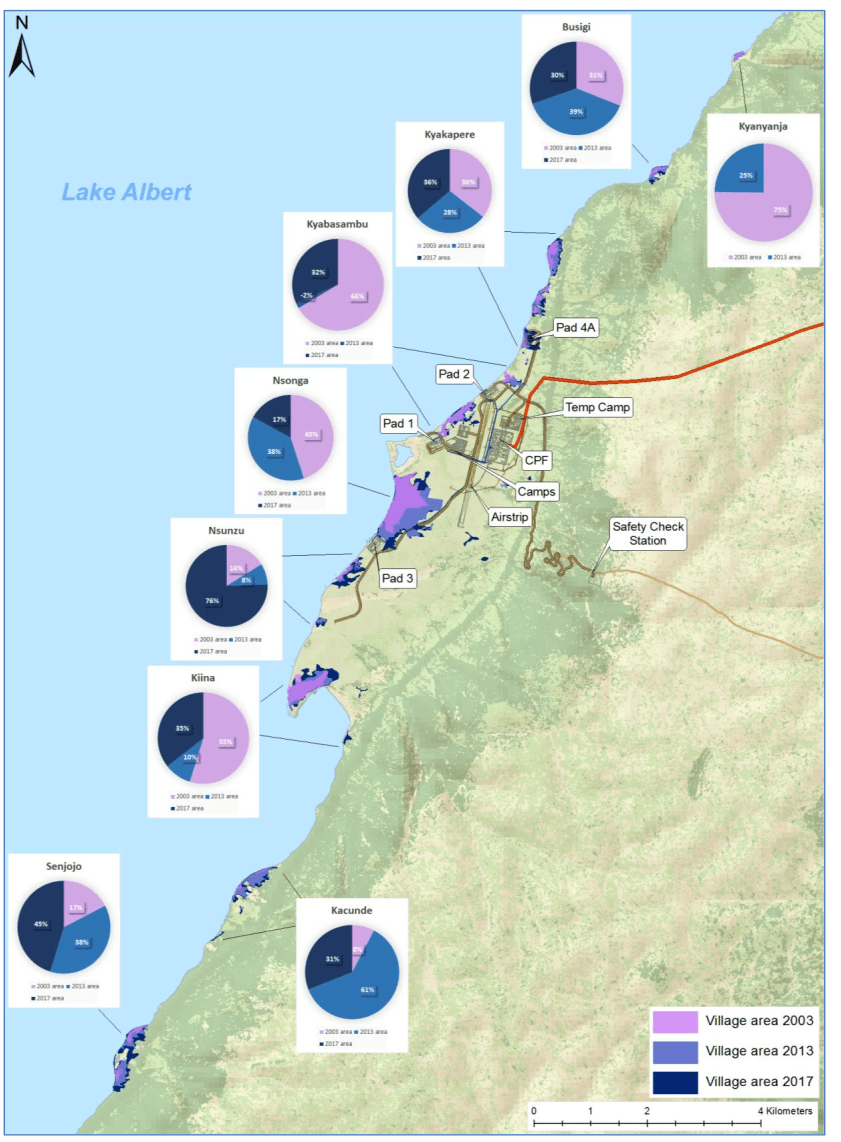

Location of villages in and adjacent to the Kingfisher project area, as well as the main Kingfisher infrastructure.7ESIA for the Kingfisher project – CNOOC Uganda Limited, Kingfisher ESIA Non-Technical Executive Summary, Sept. 2018, p. 2 (10). https://nema.go.ug/sites/all/themes/nema/docs/Vol_0_CNOOC_Kingfisher_ESIA_Non-Technical_Summary_Final.pdf#page=10.

The Kingfisher oil development project, operated by the Chinese National Offshore Oil Company Uganda Ltd. (hereafter referred to as CNOOC), is part of a massive, US$15 billion project to drill for and export significant oil reserves under Lake Albert.8See the August 21, 2024, statement of the Minister of Energy and Mineral Development of Uganda. The government claims that, “The projects include the Tilenga and Kingfisher projects in the Upstream sector, with investments upwards of US $6 billion, alongside the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) valued at US $5 billion, and the Uganda Refinery project, estimated at US $4 billion, both in the Midstream sector.” https://drive.google.com/file/d/1xJWveWCggFwEFPxHbsLwM5OMiFyVOKF8/view.

While the Ugandan government has claimed that Kingfisher and related projects will benefit the people of Uganda, those living in and around the planned development tell a different story. Many have been forcibly evicted without compensation, coerced into selling their land at inadequate prices, and deprived of their livelihoods, leaving them struggling to feed their children or pay for education. Many local residents report threats, intimidation, and violence, including sexual violence. Workers complain about safety problems and demands for bribes to obtain jobs from CNOOC and its subcontractors. Climate Rights International also received reports from whistleblowers of illegal dumping and spills of oil and chemicals that have killed fish and polluted Lake Albert.

Both the Kingfisher project and a second, larger oil development project, the Tilenga project, are jointly owned by TotalEnergies EP Uganda (hereafter referred to as TotalEnergies),9The company was previously called “Total” and changed its name to TotalEnergies on May 28, 2021. with a 56.67 percent stake; CNOOC, with 28.33 percent; and the Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC), at 15 percent. The Tilenga project is operated by TotalEnergies.

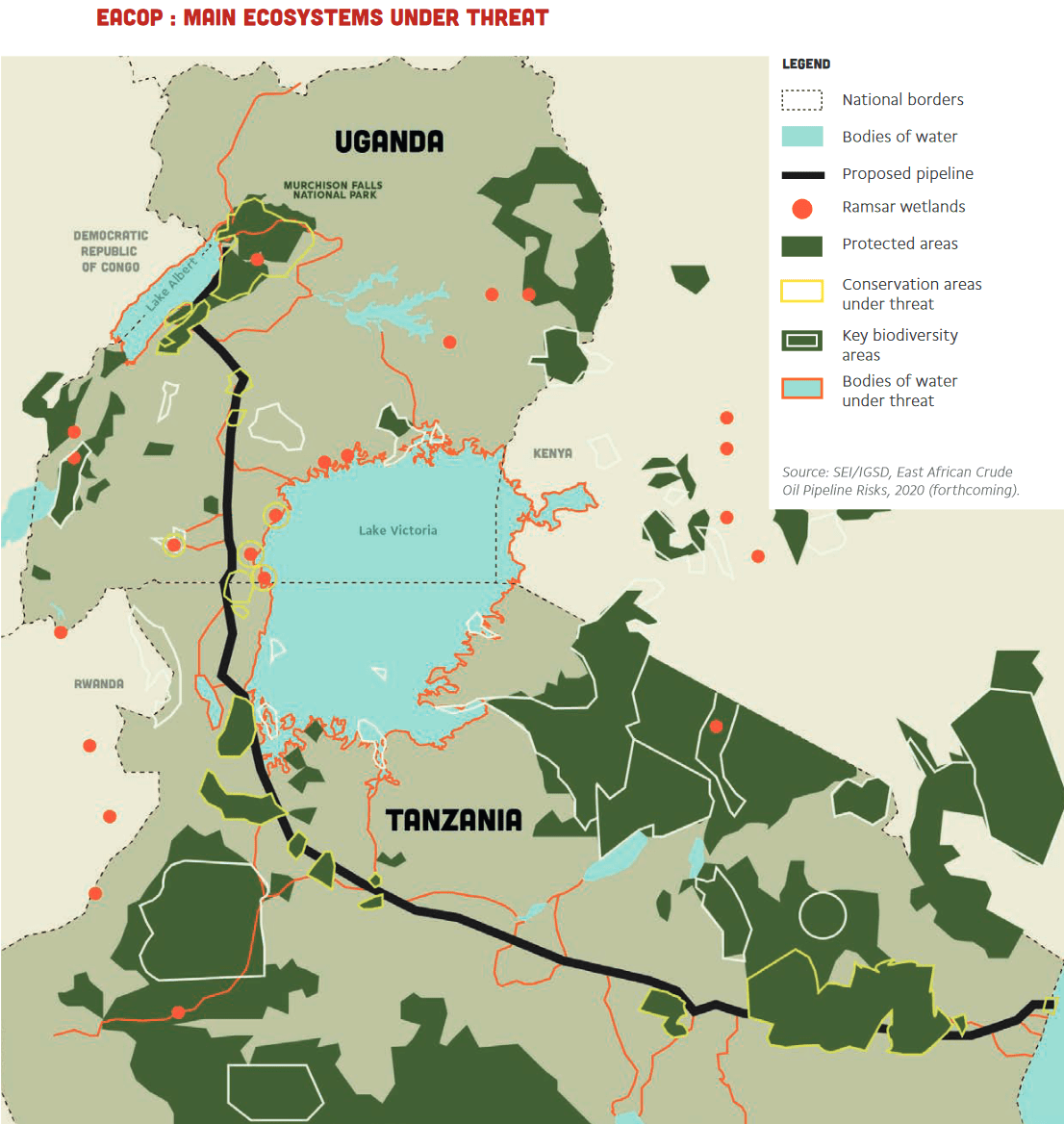

The overall project includes a massive oil pipeline (the East African Crude Oil Pipeline, or EACOP) to transport the oil from landlocked Uganda over 1,443 kilometers (897 miles) through Tanzania to the Port of Tanga. The route, 80 percent of which is in Tanzania, heads south 296 kilometers from Kabaale through Uganda to the Tanzanian border and tracks the western shore of Lake Victoria, before turning east and cutting through the heart of Tanzania’s northern savannahs and steppes toward the ocean. Due to the viscous and waxy nature of Uganda’s crude oil, the pipeline will need to be heated along the entire route, making the EACOP the longest heated crude oil pipeline in the world.10Ugandan National Oil Company, “East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline,” https://www.unoc.co.ug/midstream/east-african-crude-oil-pipeline/.

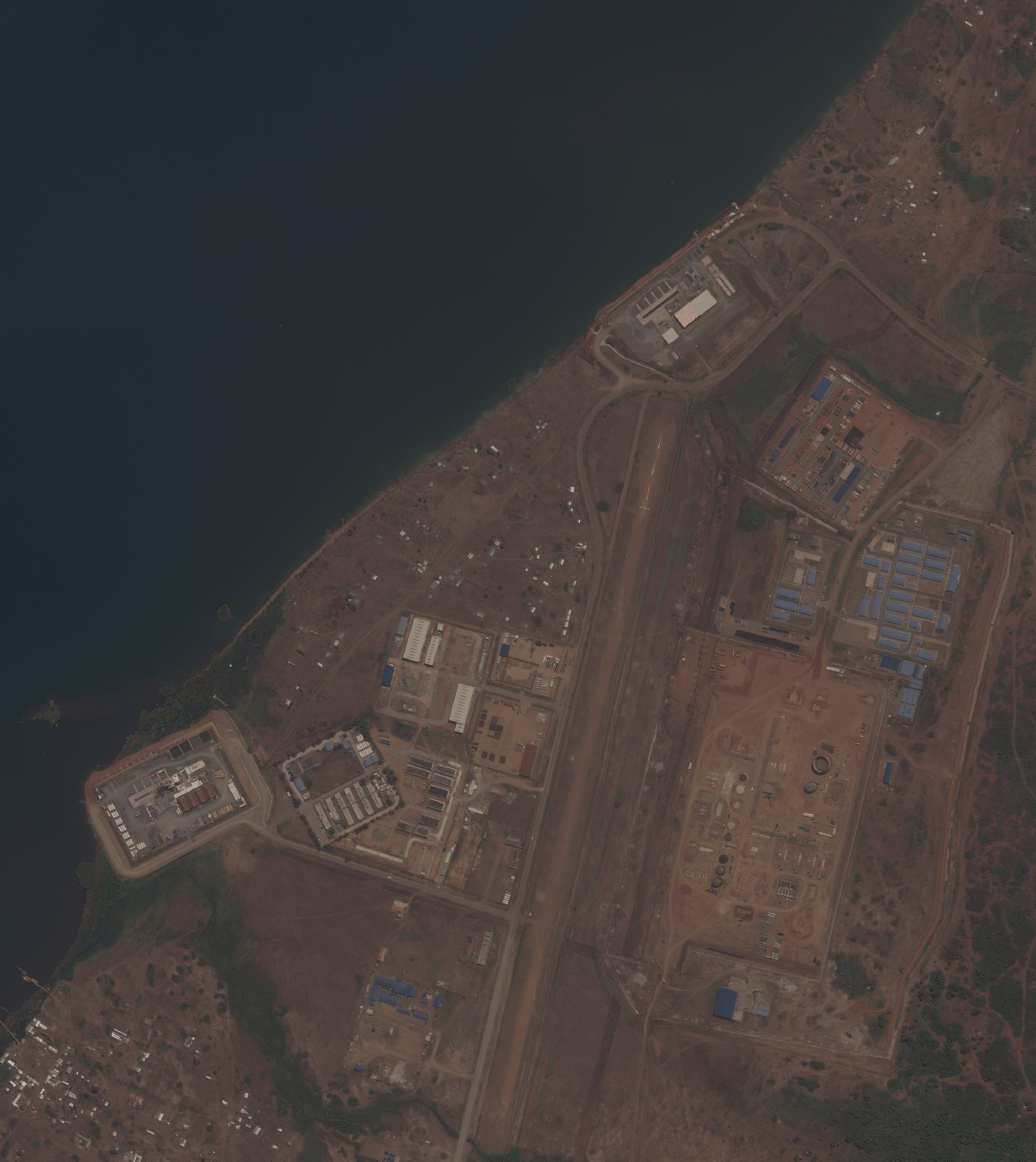

Kingfisher is located in the Buhuka Flats on the southeastern shore of Lake Albert. It includes plans for 31 wells on four well pads; 19 kilometers of flowlines to manage the flow of oil, water, and gas; construction of a Central Processing Facility to separate and treat the oil, water, and gas; a 46-kilometer feeder pipeline to transport the oil to the pipeline and a planned refinery; and other infrastructure.

The wider project’s backers have promised that it will bring significant investment and benefits to both Uganda and Tanzania, including the development of new infrastructure, technology transfer, and improvement to the livelihoods of communities along the route. Nevertheless, it has been subject to significant delays, partially due to the Covid-19 pandemic and regulatory disputes, but also as a result of strong opposition from local communities in Uganda and Tanzania, as well as pressure from domestic and international climate and human rights activists and organizations.

Once fully operational, Kingfisher is expected to produce 40,000 barrels of oil per day.11Petroleum Authority of Uganda, “The Kingfisher Development Project,” https://www.pau.go.ug/the-kingfisher-development-project/. An analysis by the Climate Accountability Institute concluded that, coupled with the output from the Tilenga field of 204,000 barrels per day, the entire oil and gas project would produce around 379 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions over 25 years.12East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline, “Overview,” https://eacop.com/overview/. Official figures are inconsistent, with a TotalEnergies document indicating production from the Tilenga project at 190,000 barrels per day. TotalEnergies, “Tilenga and EACOP, two TotalEnergies’ projects.” December 2022, p. 7. https://totalenergies.com/system/files/documents/2022-12/Tilenga_EACOP_TotalEnergies_projects.pdf#page=12. Peak annual emissions would be more than double the current annual emissions of Uganda and Tanzania combined.13Climate Accountability Project, “East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline: EACOP lifetime emissions from pipeline construction and operations, and crude oil shipping, refining, and end use,” report, Nov. 21, 2022, https://climateaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/CAI-EACOP-Rptlores-Oct22.pdf. Damian Carrington, “‘Monstrous’ east African oil project will emit vast amounts of carbon, data shows,” The Guardian, Oct. 27, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/oct/27/east-african-crude-oil-pipeline-carbon. Like all new oil and gas projects, its development is incompatible with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C° warming target and a livable planet.14Paris Agreement, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement.

In addition to the obvious climate harms, opponents argue that the project – one of the largest oil and gas projects in East African history – will entail numerous environmental and social risks, including physical and economic displacement, a mismanaged and delayed compensation process, threats to livelihoods, the loss or destruction of sites of spiritual value, and significant disturbance to one of the most ecologically diverse and wildlife-rich regions of the world.

Kingfisher is a major priority for the Ugandan government and its autocratic leader, Yoweri Museveni, in power since 1986 and one of the world’s longest serving leaders. Since the arrival of CNOOC in 2012-2013, his government has deployed large numbers of the Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces (UPDF) in the Kingfisher area. General Wilson Mbadi, Chief of Defense Forces until March 2024, has made it clear that the UPDF has been deployed to ensure that no one disrupts CNOOC’s operations, saying that extra measures would be put in place: “First of all, currently we have about three layers of security. You must have seen some physically there. That is the first security point. They are there. And then working with our marine forces who patrol the lake. And then we have the fisheries protection unit. And we are putting in place other measures.”15“UPDF to beef up security for Albertine Oil and Gas,” The Independent, Oct. 4, 2021, https://www.independent.co.ug/updf-to-beef-up-security-for-albertine-oil-and-gas/. The oil and gas police, a special unit of the Ugandan police, also has a very significant presence in the Kingfisher area.16ChimpReports, “Reshuffle: Byakagaba Moved Back to Oil Police,” Sept. 18, 2017, https://chimpreports.com/reshuffle-byakagaba-moved-back-to-oil-police-s-kasigye-to-head-afripol-bureau/.

In addition to other abuses by the UPDF documented in this report, this vast military presence has been used to intimidate the local community and chill opposition to the Kingfisher project. Those who do speak out have faced serious harassment, intimidation, and, in some cases, violence. In June 2024, Stephen Kwikiriza, who has documented the environmental devastation and human rights violations suffered by his community because of the Kingfisher project, was abducted by the UPDF in the capital, Kampala, and held for five days, during which he was interrogated and tortured before being dumped on the side of a road.17“Detained Uganda anti-pipeline activist released,” Al Jazeera, June 10, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/6/10/detained-uganda-anti-pipeline-activist-released; Climate Rights International, “Uganda: Independent Investigation Needed for Abduction, Beating of EACOP Activist,” news release, June 11, 2024, https://cri.org/uganda-independent-investigation-needed-for-abduction-beating-of-eacop-activist/.

A woman sits in the Kingfisher oil development area. © Mathieu Ajar

While there has been significant reporting on the human rights and environmental violations associated with the Tilenga project (see Chapter I below), the Kingfisher project has not received much attention from Ugandan and international organizations or the media. This is partly due to significantly greater challenges in accessing and investigating the Kingfisher project, not least because of the heavy military presence and a militarized atmosphere that makes criticism and even fact-finding risky for local residents and organizations.

This report is the first in-depth investigation into the human rights consequences of the Kingfisher project. Local residents interviewed by Climate Rights International described:

Below are examples of abuses in the Kingfisher area, each of which is documented in greater detail in subsequent chapters of the report.

The Land Acquisition and Resettlement Framework, signed by CNOOC, TotalEnergies, and the Ugandan government in December 2016, includes commitments to adhere to best practices in land acquisition, ensuring fair and adequate compensation and resettlement for affected landowners and communities.18Land Acquisition Resettlement Framework, Petroleum Development and the Albertine Graben,” December 2016, Table 4, https://totalenergies.ug/system/files/atoms/files/land_acquisition_and_resettlement_framework.pdf. The Framework said it would align with the International Finance Corporation (IFC) Standards, notably Performance Standard 5 (PS5) on Land Acquisition and Involuntary Resettlement. These standards require that displacement should be avoided where feasible, and minimized whenever it is unavoidable by exploring alternative project designs. Moreover, the standards require that displaced communities and persons be offered compensation for loss of assets “at full replacement cost and other assistance to help them improve or restore their standards of living or livelihoods.”19Performance Standard 5 states that “projects which reduce communities’ access to natural resources and land should minimize negative implications in this respect. Please see below in Chapter 2 for more details. International Finance Corporation, “Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability,” Jan. 1, 2012, https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2010/2012-ifc-performance-standards-en.pdf.

The reality is that the “measures” to “secure” the oil resources cited by General Mbadi have included large numbers of forced evictions. Former residents of villages in the Kingfisher area described being forcibly evicted, often with little or no notice, by the UPDF. Interviewees described being ordered to leave and fleeing with what little they could carry. Those who returned to their villages afterward to try to collect belongings reported finding that their homes had been emptied and, in some cases, demolished. Other assets, such as goats and chickens, were missing. In some cases, entire villages have been emptied, with military buildings installed in their place. The UPDF also expelled the inhabitants of Kyabasambu, the village where the majority of the Kingfisher project’s oil installations are located.

Solomon Atuhaire, who had been living with his family in the village of Kiina on land passed down by his father, described what happened in his village in 2021:

By 6 a.m., the village was swarming with 30 to 40 military personnel. The soldiers declared: “We don’t want you here.” People protested that they had nowhere to go, prompting the UPDF to start shooting, some shots fired into the air, others aimed to scare. The villagers began to flee. I immediately entered my house, told my wife we are leaving, closed the house and the shop, and directly left.

When Atuhaire was finally allowed to go back to collect his belongings, almost everything was gone.

Only my bed without the mattress remained. My shop was completely empty. And I had just seven goats left.20Climate Rights International interview with Solomon Atuhaire.

Henry Lwanga explained to Climate Rights International that he lived on the shores of Lake Albert until 2020, when the Ugandan military forced him to leave:

I was in Kyabasambu village when the UPDF [Uganda Peoples’ Defense Force] came one night during the evening and said that by tomorrow at 7 a.m., I should have left the place. Around 10 soldiers were there with guns. The police were also there. […] The majority of the people that night ran and slept in the school. Me, I just left directly with some small things I could carry, thinking I could come back later to transport the other bigger things. But when I came back during the morning at 7 a.m., everything had already disappeared. So I also lost my 13 iron sheets, my solar battery, my 13 goats, chickens, clothes, bed, sofa. The house was totally empty. I lost my boat afterward.

Lwanga said he has received no compensation for his losses and has struggled to support himself and feed his children:

I have seven children, five of my own and two from my brother who died. […] We have one meal per day, the same for everyone in the family. Sometimes even that meal is missing, and we take only tea.21Climate Rights International interview with Henry Lwanga.

Simon Namukasa, who lives in Nsunga, told Climate Rights International that soldiers told him that the UPDF intended to gradually drive out all the inhabitants of the area. He said that the presence of the Ugandan army remains extremely high in the area.

In 2018 or 2019, the UPDF told me that they don’t want anyone [living] on the lake… They created a lot of barracks on every shore.22Climate Rights International interview with Simon Namukasa.

Satellite images of the village of Kiina, taken on January 8, 2019 (before eviction), and June 15, 2024 (after eviction). The majority of the dwellings (the brown structures especially) have disappeared.23GPS coordinate: 1.2063711113784081, 30.71927691598637

Villagers who were offered compensation for their land but did not accept, either because they felt the compensation was inadequate or because they did not want to leave their land, told Climate Rights International that they were threatened and intimidated into selling. CNOOC agents were sometimes accompanied by UPDF and police forces, which significantly increased the pressure on residents to accept the compensation.

Samuel Ochieng, who is affected by the CNOOC feeder pipeline in the village of Ndongo, explained:

At first for clearing the bush on my land, CNOOC used to move with UPDF. After signing [the compensation agreement], after clearing the land and putting the pillars, CNOOC brought their security guards.24Climate Rights International interview with Samuel Ochieng.

Sam Opol also spoke to Climate Rights International about the close ties between the UPDF and CNOOC:

I’m neighbors with UPDF. They [soldiers] are sleeping on containers where is written CNOOC. […] They got water from a pipe which came from a CNOOC camp.25Climate Rights International interview with Sam Opol.

Joseph Mugisha from the village of Nzunsu B told Climate Rights International that CNOOC agents threatened him with losing everything if he persisted in his refusal to sign the “voluntary” compensation agreement:

I was not happy and didn’t want to sign at the beginning. But [CNOOC] told me that if I didn’t sign, the land would be taken freely.26Climate Rights International interview with Joseph Mugisha.

Andrew Odongo, who lives in a village along the feeder pipeline, said that threats that he would lose everything without compensation prompted him to sign:

They used to tell us, if you refuse to sign, your land will be taken freely and you as an individual, you can’t let the government programs fail to move on. At first, I wanted to refuse to sign, because the money was too little. They told me that all the other people agreed, so if I refuse they will take my land freely. So I had to accept and sign.27Climate Rights International interview with Andrew Odongo.

The large majority of those interviewed by Climate Rights International who received cash compensation said that the amounts they received were far too low to facilitate the purchase of land comparable in terms of size and quality to the land taken by the project.

Mercy Nalubwama, from the village of Nongo, along the feeder pipeline, told Climate Rights International:

They took a quarter of my land, they pushed me to sign for 1.5 million, and yet I had so many crops in this garden. So that money was too little to buy somewhere else. CNOOC said the price of compensation comes from the district. I used to dig on that land, and could get some good money per season. Now I’m so much afraid, life is so hard. [Before] children could go to school, but now the remaining piece of land is not enough anymore.28Climate Rights International interview with Mercy Nalubwama.

Even some of those who were given replacement houses after losing their homes to the project reported that the replacement homes did not make up for what they had lost. As one affected person reported:

They built me a small, tiny house with three rooms, whereas before, my house had six rooms. And for the land, I haven’t received anything. I had two plots. Now it’s even less than a plot because they have built other houses right next to mine, in a row.29Climate Rights International interview with Alex Kato.

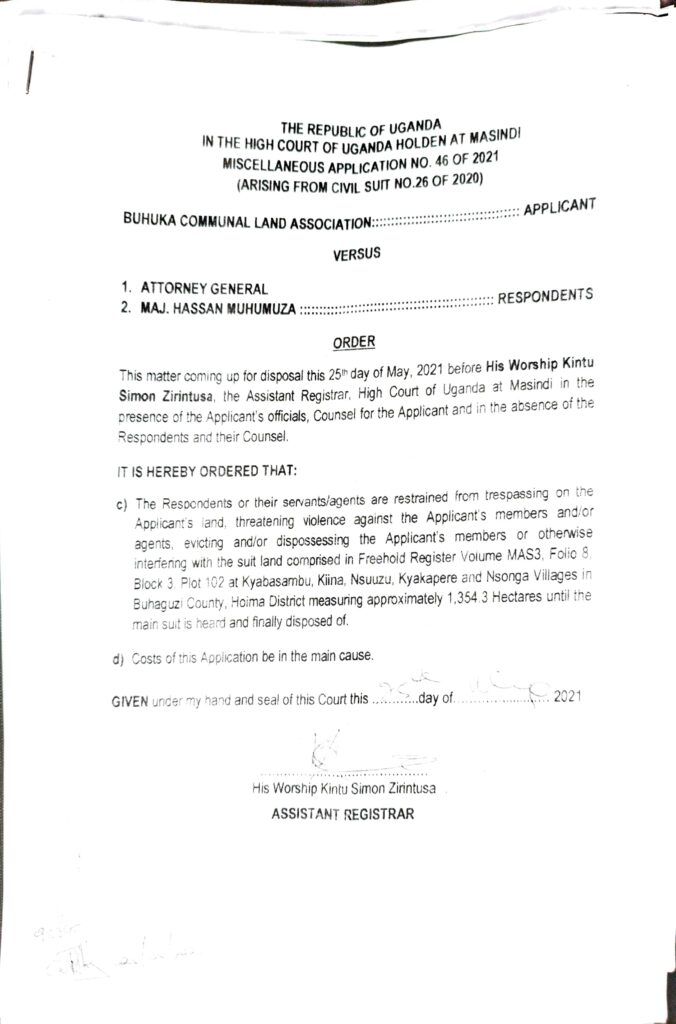

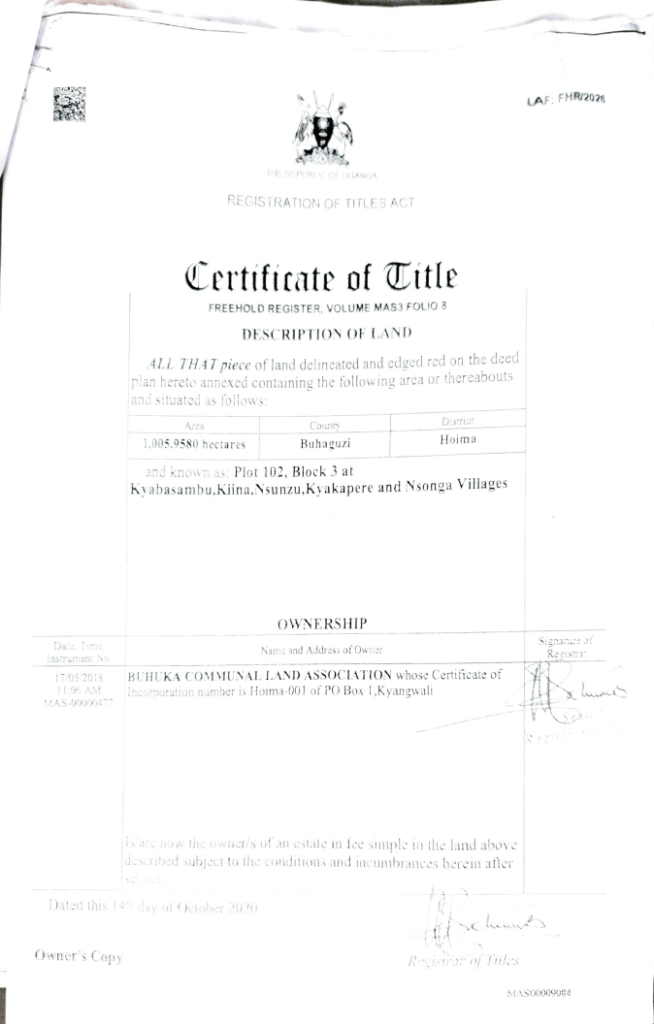

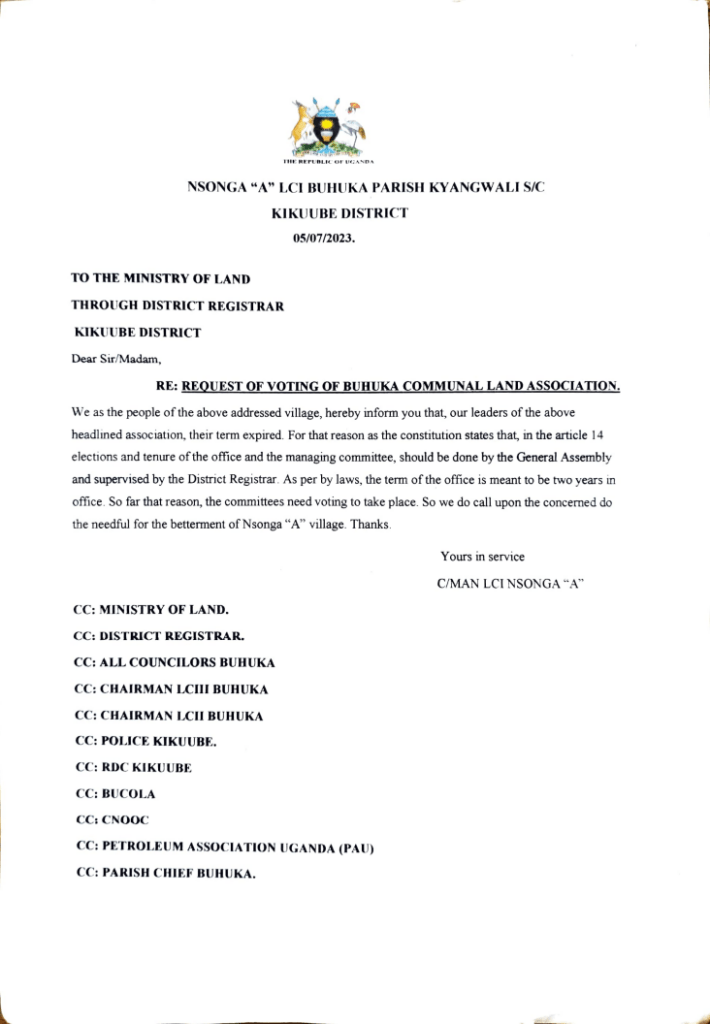

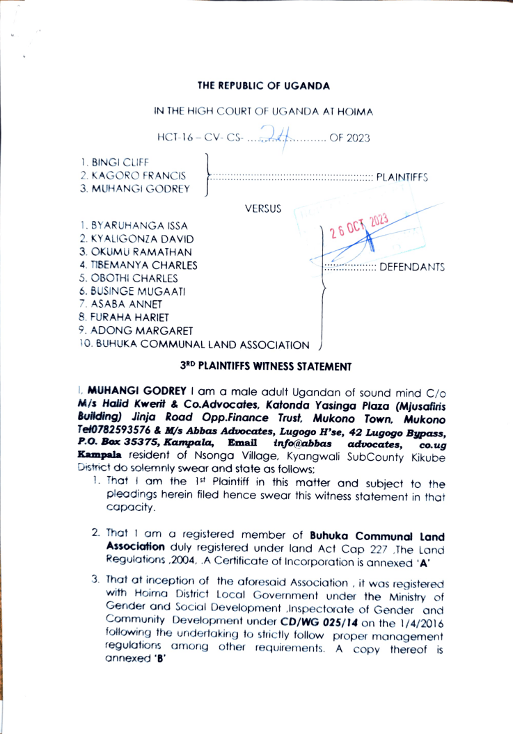

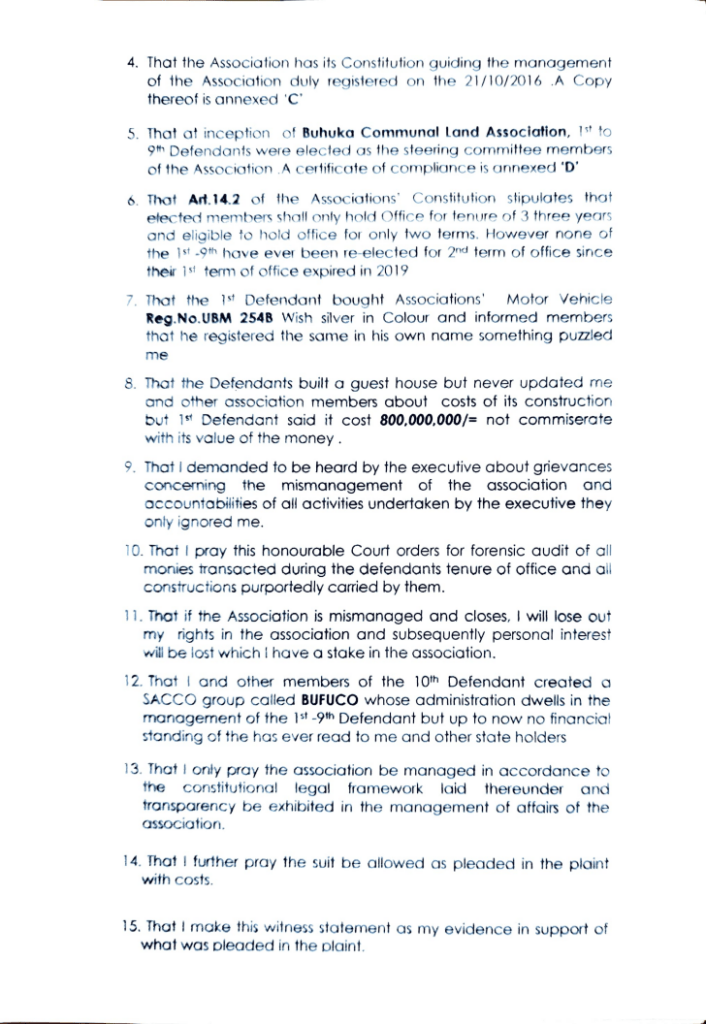

The problem appears to be much greater for people residing on communal land. None of those interviewed by Climate Rights International who were residing on communal land reported that they had received compensation for their homes, crops, or other assets. Those residing on communal land said that CNOOC did not contact them during the land acquisition process. Instead, to acquire communal land in the Buhuka Flats villages, CNOOC operated through a “Communal Land Association” named the Buhuka Communal Land Association, or Bucola, which was established almost exclusively for this purpose. It is unclear how much, if any, compensation CNOOC has paid to the association to acquire land.

Individuals residing in villages in Buhuka Flats have described harassment and evictions by Bucola, and being required by Bucola to pay to resettle on and use communal land. Those expelled said that they never received any compensation for their livestock, houses, or other assets. Ballack Watcho, who lived in Nsunzu village explained that:

When CNOOC wants land, now Bucola just tells you to leave, even if you have a house, and you don’t receive any compensation.30Climate Rights International interview with Ballack Watcho.

Many of those evicted from their homes and lands are struggling to feed their families and educate their children. Edward Nsereko, formerly of Kyabasambu, describes his experience:

After being chased from Kyabasambu, we thought that Bucola would give us somewhere to live and use the money from the association with the support of CNOOC to construct something, which was in vain. They didn’t do anything. From Kyabasambu, I moved to Nsonga. I bought another plot in Nsonga from another person. I bought one plot. Then I constructed a house of plastic sheets. Even eating is very difficult.31Climate Rights International interview with Edward Nsereko.

While the Resettlement Action Plan for the Kingfisher project has never been made public, one possible reason for the failure to provide compensation is that those involved with the project have only treated those with individual land titles as “project affected persons” entitled to compensation and/or resettlement.32A Resettlement Action Plan (RAP) for the Kingfisher project is a strategic document outlining the procedures and actions to be taken for relocating and compensating people affected by the project’s land acquisition. The RAPs for the EACOP and Tilenga projects are public, but CNOOC has not published the one for the Kingfisher project. However, many of the families who have been displaced lived on communal land to which Bucola, according to CNOOC’s own studies, has obtained a land title.33CNOOC, Kingfisher ESIA, volume 4C, Study 10: Socio-Economic Assessment, June 2018, https://cnoocinternational.com/-/media/cnooc-images-and-files/operations/middle-east-and-north-africa/uganda/esia-documents/vol_4_cnooc_kingfisher_esia_ss_10_sia_final_print_ready_20181120#page=64 , p. 44 (64)

Victims told Climate Rights International that efforts to complain to CNOOC and the police have been unsuccessful. Some of the people who resisted relocation or complained were told by CNOOC officials that the only way to challenge the compensation offered was to go to court, something they could not afford to do. Samuel Ochieng from the village of Ndongo, which was affected by the feeder pipeline, explained:

We continued to complain, but we were told that if that is not favorable to you, you can go to court. But for us, we couldn’t afford to go to court. So finally we had to sign. We didn’t have enough capacity to go and report to court, to sue the government in court.34Climate Rights International interview with Samuel Ochieng.

Some affected individuals told Climate Rights International that they lacked knowledge and understanding of the content of the documents they were signing. Emmanuel Kizza said:

I signed because after they told me that the land would be taken, I thought it was just to confirm I understood the pipeline was going to pass there. But later, after signing, they told me that I was going to receive this amount.35Climate Rights International interview with Emmanuel Kizza.

The Ugandan government has not provided legal aid or other legal assistance to people who allege they have received no or inadequate compensation.

Goats wandering in front of an abandoned house in the Kingfisher area. © Mathieu Ajar

While many residents farm the land, the primary economic activity in the Buhuka Flats is fishing. However, since the arrival of CNOOC and the Ugandan military, both fisherfolk and fish sellers report that the UPDF fishery and marine units regularly seize and burn boats that don’t comply with new regulations banning smaller boats, arrest fisherfolk and demand bribes for their release, and seize fish from fish sellers. Many allege that this is part of a campaign to drive people out of the Kingfisher area, claiming that the restrictions on boat, net, and fish sizes are much more aggressively enforced at the Kingfisher area than on other parts of Lake Albert.

Vincent Yeno, from Kyehoro, explained that in August 2022 UPDF soldiers burned boats that were smaller than the size mandated by new regulations. He said that the soldiers refused to let fisherfolk modify their boats, which would have been much cheaper than building new ones:

It was an abrupt issue, so I can’t tell how many boats were burned, but so many. People used to hide some of them, but now all of them are burned. There was no time to ask them to enlarge the boat, the UPDF directly started to burn the boats.36Climate Rights International interview with Vincent Yeno.

Boats and fishing nets burned by UPDF soldiers in the Kingfisher area. © Environmental Governance Institute

Sarah Namazzi, a member of the fisherman’s association from the same village, said that the UPDF burned more than 300 small boats that day. She said the UPDF commander told the community:

If you can’t afford these new boats, you should go away from that landing site.37Climate Rights International interview with Sarah Namazzi.

The UPDF regularly arrests those fishing in boats or with nets that don’t meet the new regulations, demanding bribes for their release. Benjamin Mutebi, from Nsunzu B, explained what happened when he was arrested:

From the water they bring us to Buhuka police station. Then the next day, we were transferred to Kikuube district to the prison. I spent one week there and never faced a judge. The negotiation was between the Officer Commander from Kikuube prison and the family. The family had to pay 200,000 shillings per person.38Climate Rights International interview with Benjamin Mutebi.

Many local residents told Climate Rights International that the harassment and extortion by the UPDF have made it difficult for fisherfolk in the Kingfisher area to make a living, leading many to give up the profession or try to move to another area of the lake. Victor Luganda, a 37-year-old fisherman who just spent several months in prison, unable to bribe the army for his release, told Climate Rights International:

I want to go to Kaiso. Even in Kaiso, there are soldiers. But they don’t disturb the fishermen like here, because they allow them to fish.39Climate Rights International interview with Victor Luganda.

Livestock farming is the second most prevalent business activity in the Kingfisher area. Many have lost all or part of their livestock during forced evictions by the UPDF. Those who managed to flee with some of their cattle often had to leave behind their pigs, chickens, and goats.

Solomon Atuhaire, who was evicted from Kiina, said that he had approximately fifty goats, but after the eviction, “I had just seven goats remaining there.”40Climate Rights International interview with Solomon Atuhaire.

Farmers who have remained in the area have seen a significant reduction in grazing areas due to land confiscated by the oil project. CNOOC has not provided alternative resources for those who have lost access to grazing land. This has resulted in animals having insufficient grass for nourishment, drastically reducing milk production.

Charles Kwesiga, a farmer who lived in the village of Kina, shared his experience:

Yes, I have been affected by the oil project. […] The grazing area was initially very large, it was adequate. But when the oil companies arrived, the grazing area became very small. I was grazing on the communal land in Kiina village. Almost half of the land has been taken. Because the land became too small, the milk yield per animal has significantly decreased. People have to sell their cows, and many are leaving [the area] because of that.41Climate Rights International interview with Charles Kwesiga.

Farmers also face increasing challenges due to land acquisitions by CNOOC and its subcontractors. Godfrey Lubwama explains that his family lost part of their land:

Our land, a part of it, was taken by the oil companies for the road.42Climate Rights International interview with Godfrey Lubwama.

The forced evictions, lack of or inadequate compensation, and loss of livelihoods have had a devastating impact on the standard of living of much of the local community. Many have struggled to feed themselves and their families and to pay for education. Some of those displaced have been unable to afford replacement housing and are living in homes constructed of plastic sheets.

Stephen Katenda, who was evicted from Kyabasambu, explained:

I have a temporary house, plastic sheet. Like the one they give for the refugees. Because renting was too expensive. A lot of people have this type of plastic sheet house.43Climate Rights International interview with Stephen Katenda.

A tent used by people evicted from their homes as a result of the Kingfisher project. The drilling rig can be seen in the background. © Mathieu Ajar

Solomon Atuhaire, who was driven from Kiina by the UPDF, can no longer afford to educate his children:

Life was okay, we could eat, I could pay school fees for my children, even good schools. Some of my children were studying in a school in West Nile (in a boarding school), some others at Starlight School. Now I don’t have a real job or income. My children are not in school anymore.44Climate Rights International interview with Solomon Atuhaire.

Lawrence Ssemwogerere, from the village of Nsunzu A, explained his plight:

I’m now 41 years old. I was born by the lakeside. I don’t know any other work. UPDF arrived and blocked us from fishing. We know everything about fish when fish is good and bad, which months we can fish and what. But since these units came, we don’t know what to do. Before we had a lot of cash, but now life is difficult.45Climate Rights International interview with Lawrence Ssemwogerere.

Impoverishment also appears to have led to some husbands and fathers abandoning their families, causing even greater poverty for the women and children left behind. Rose Belieda recounted how she and her ten children lost all contact with her husband on the day of their eviction from Kyabasambu in 2020:

It was in the morning when soldiers came and ordered us to leave immediately. We had very little time to evacuate. Consequently, properties were left behind, including animals. We left Kyabasambu and relocated. My husband ran away and abandoned me with our ten children without any support. We live under a plastic sheet. All ten children stay with me, and securing food is very challenging. Sometimes, neighbors and friends, feeling pity for us, support us with food. After leaving Kyabasambu, I first stayed in a school for six months, then built a house with plastic sheets. My husband went in another direction and never contacted us again.46Climate Rights International interview with Rose Belieda.

Forced evictions and the accelerated development of the oil project by CNOOC has had a significant impact on the evictees’ relationship with their deceased family members, ancestors, and cultural traditions.

Many graves are located in areas from which communities have been expelled. In some cases, the expelled families have managed to excavate the graves, performing some of their traditional rituals. But in many cases, this has not been possible. Michael Omondi explains that companies working in the Kingfisher area have excavated many graves without any of the traditions being respected:

In Kyabasambu, many graves were excavated. Those who complained have received compensation to perform the rituals. But for some other graves where nobody complained, they have not performed any rituals.47Climate Rights International interview with Michael Omondi.

David Kato told Climate Rights International that the former residents of expelled villages can no longer visit the sites to continue performing the rituals that they believe are necessary to conduct regularly to respect their ancestors and culture:

People can’t visit their graves due to some restrictions. Some people have complained, but there is no way forward to help them with this.48Climate Rights International interview with David Kato.

The treatment of graves and the rites associated with them, and the denial of access to remaining graves, are inconsistent with IFC’s Performance Standard 8 on respecting the Cultural Heritage of affected communities, with which CNOOC agreed to comply.49International Finance Corporation “Performance Standard 8 Cultural Heritage,” 2012, https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2010/2012-ifc-performance-standard-8-en.pdf

Much of the oil-related activity within Kingfisher, from building roads, camps, and houses to installing oil rigs and conducting drilling operations, is carried out by CNOOC’s subcontractors. These subcontractors include foreign companies, Ugandan companies, and joint ventures between foreign and Ugandan companies. Community members who have sought jobs with these companies reported poor treatment including excessive hours, low wages, hazardous working conditions, failure to pay promised wages, failure to provide employment contracts, and demands for bribes to obtain jobs.

Many of those interviewed complained of very low wages and failure to pay promised wages. Workdays are often longer than 10 hours, the legal limit under Ugandan law, and frequently seven days a week, also in violation of the law.50Uganda Employment Act, 2006, sec. 51 & 53. https://ulii.org/akn/ug/act/2006/6/eng%402006-06-08 Isaac Mubiru, who worked for various companies in the sector, said:

The conditions were too tough. We had to work from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m., with a break of 30 minutes. Seven days per week. Vacation requests were denied, with responses such as, “Not possible, because their contract is for a short period, so they don’t need to have a break.”51Climate Rights International interview with Isaac Mubiru.

Climate Rights International has collected numerous testimonies from workers and ex-workers who say they never signed a contract with their company. For example, Benjamin Okello explained:

I never signed a contract. They said the company got a contract, but not me with them. They told you if you work well, you can continue even after three months, but I never signed a contract.52Climate Rights International interview with Benjamin Okello.

Kenneth Kiwanuka, who worked for a subcontractor for six months in 2023, told Climate Rights International:

I was paid only half for the last four months. I complained and continued to complain. [They] replied that the money they are getting doesn’t allow them to pay everything, but directly when they will receive the money they will be paid. But that has never changed.53Climate Rights International interview with Kenneth Kiwanuka.

Some residents told Climate Rights International that they had to pay bribes in order to be hired. They explained that they often must first pay the chairman of their village to obtain a recommendation letter, which is mandatory to show they are a resident of the affected area. They then also have to pay the company recruitment officers to secure a job.

Workers in the Kingfisher industrial zone. © Environment Governance Institute

Several accidents were reported to Climate Rights International, some allegedly due to the lack of or poor quality of protective equipment on the sites. Moreover, medical care for injured workers appears to vary greatly depending on the subcontractor. According to John Palot:

I saw safety was not highly maintained. Care about someone victim or injured was not good. Safety gears are old and weak. Helmets are not enough for everyone.54Climate Rights International interview with John Palot.

Numerous women told Climate Rights International about sexual violence resulting from threats, intimidation, or coercion by soldiers in the Kingfisher project area. Many reported that soldiers threatened them with arrest or confiscation of their fish merchandise unless they agreed to have sex with them.55Climate Rights International interviews with Brenda Nakasumba and Justine Baguma. We also received reports of sexual violence by managers and superiors within oil companies operating at Kingfisher, including one involving a CNOOC employee.

Jennifer Akello explained:

CLOs are the ones to support communities to get jobs, but they request for bribes. They may ask like 50 000. If you don’t have money, it’s common they ask favor of sex to get a job. And in some cases, after using them [the women], they end up without even getting a job.56Climate Rights International interview with Jennifer Akello.

Solicitations for sex reportedly also occur in the workplace. Two women reported solicitations and demands for sex from company superiors involved in the Kingfisher project. Christine Nanyanzi told Climate Rights International:

At the job, if you refuse to sleep with your boss, you can be chased away very fast.57Climate Rights International interview with Christine Nanyanzi.

Several women reported that UPDF soldiers threatened them with arrest or confiscation of their property unless they agreed to have sex with them. Women explained that, to avoid harassment by soldiers and to be allowed to continue their trading activities, they sometimes had sex with soldiers to be able conduct business.

As Justine Baguma told Climate Rights International:

Another problem is the UPDF disturbing the women when they trade fish. They arrest them and sometimes even force them to sleep with them.58Climate Rights International interview with Justine Baguma.

All of these abuses are exacerbated by a lack of access to the legal system to obtain justice. According to a 2020 report by Fédération internationale pour les droits humains (FIDH, or the International Federation for Human Rights), “[n]ational authorities themselves acknowledged that, save for a handful of individuals who had the time and money to go to court, district tribunals had not been effective in dispute resolution… [I]n the instances where legal actions were identified, irregularities in the procedures as well as circumstances affecting the independence of judicial authorities often appear… judicial remedies appear more as a threat than as a tool for communities to defend their rights. Residents across a swath of villages narrated situations in which legal actions were used to coerce them into signing compensation agreements.”59International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and Foundation for Human Rights Initiative (FHRI), “New Oil, Same Business? At a Crossroads to Avert Catastrophe in Uganda,” report, September 2020, p. 43.

The 2023 World Justice Project Rule of Law Index ranked Uganda as being one of the worst countries in the world for the rule of law and access to justice.60World Justice Project Rule of Law Index 2023: Uganda is ranked 125th across 142 countries, https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/country/Uganda. Also in 2023, Transparency International ranked Uganda 141 out of 180 countries globally for corruption.61Transparency International, “Our Work in Uganda,” https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/uganda

It is against this backdrop that, in addition to threatening affected individuals that their land would be taken without compensation if they refused to sign, CNOOC agents explained that people who were unsatisfied had the option of suing the Ugandan government. For many this wasn’t an option, as Patrick Kyeyune explained to Climate Rights International:

The CNOOC official told us they got the amount from the district, so if you are not okay with the amount, go to hire a lawyer and go to court. As I couldn’t afford to hire a lawyer, I just agreed and signed.62Climate Rights International interview with Patrick Kyeyune.

The development of the Kingfisher project has led to the degradation of the physical environment, including land, water, and air pollution. Fisherfolk report seeing oil slicks and dead fish in the lake, and a drastic reduction in fish in the Kingfisher area. Oil and chemicals have been discharged directly into the lake, as well as on land, where they subsequently flow into the lake.

The impact is significant. Duncan Kisitu explained that he had seen a pipe from the oil well pad at Kyabasambu spilling oil into the lake:

They pour oil in the water in the lake, and that oil kills fish. We see some pipes that cross a stream of water, and pour oil into the stream of water, in the lake.63Climate Rights International interview with Duncan Kisitu.

Emma Prelo, a cattle keeper, explained that oil pollution from the drilling rig has also been detected on the grass fields where the animals graze:

Sometimes some oil just pours it into the community and on the grass. And with the rain, that takes this even to the lake.64Climate Rights International interview with Emma Prelo.

Climate Rights International interviewed two people who worked for several months with China Oilfields Services Limited (COSL), the drilling service contractor for CNOOC.65“Oil Drilling Begins at Chinese-run Field in Uganda,” VOA, Feb. 4, 2023, https://learningenglish.voanews.com/a/oil-drilling-begins-at-chinese-run-field-in-uganda/6935786.html. They explained that their former supervisor, a Chinese national, instructed them to empty the contaminated water basins from the drilling rig directly into the lake or onto vacant land around the oil well pad using a pipe and a water pump. These basins contain a mix of water, oil, and chemicals used in drilling activities. Quinton Kizza, one of the two ex-workers, reported that:

The main issue was dumping. […] There were some pits to collect water. […] The boss said we should pour that water into the lake. We used a water pump to take that water to the lake. From the mud tanks, we put that water in the pits. There was also some oil in this pit. So, you put the water pump in the pits to pour that directly into the lake.66Climate Rights International interview with Quinton Kizza.

Philip Musoke, another former COSL worker, explained about the basins:

They are designed to collect all the water, drill water, chemicals, muddy water to not go directly to the lake. It’s where they were supposed to be collected by a waste company. All of them when they are full, they just put it in the lake. They asked me to pump that water. […] Or we could pump it to the hill, but it’s the same. It goes to the lake afterward. [They] pump only at night.67Climate Rights International interview with Philip Musoke.

Quinton Kizza confirmed this:

We dumped that water around 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. during the night. We did that several times.

Residents from Nsunzu B village, in front of the drilling rig of the Kingfisher project. © Mathieu Ajar

In addition to polluting the environment and the lake through discharges of contaminated liquids, construction work, particularly of the feeder pipeline, is having an impact on different sources of water used by local residents.

Samuel Ochieng shared his experience since the beginning of construction activities at Kingfisher:

Before, I used a water body near my house. But now they have destroyed it when they dug the hole for the pipeline. The water is still there but very dirty now, so it’s not possible to use it anymore.68Climate Rights International interview with Samuel Ochieng.

Peter Musoke, a local resident, described the impact of the construction work on the feeder pipeline over many months:

Their pipeline corridor passes through some water stream and contaminated our water. […] Some managed to find water very far, some others who couldn’t had to use the dirty water.69Climate Rights International interview with Peter Musoke.

Feeder pipeline for the Kingfisher project passing through farmland in Kikuube district. © Mathieu Ajar

If ongoing risks to or adverse impacts on project-affected communities are anticipated, IFC Performance Standards requires a project to “establish a grievance mechanism to receive and facilitate resolution of the affected communities’ concerns and grievances about the client’s environmental and social performance.”70International Finance Corporation, “Performance Standard 1 Assessment and Management of Environmental and Social Risks and Impacts,” Jan. 1, 2012, para. 35, https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2010/2012-ifc-performance-standards-en.pdf

The ESIA concluded that the CNOOC Grievance Mechanism, which was already in use when the ESIA was written, was not thought to be effective by many villagers. An August 2024 petition to CNOOC signed by 268 residents of the Kingfisher area makes it clear that the grievance process is still not working: “CNOOC should establish an independent, fair grievance mechanism within the community to facilitate open communication and allow the community members to voice their concerns regarding the project and access compensation. It is crucial for CNOOC to pay close attention to the issues raised and address them appropriately.”71Kingfisher affected people’s network, “Petition requesting CNOOC to address the grievance faced by the Kingfisher project host communities in Kikuube district,” August 5, 2024, https://cri.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/English-Petition-requesting-CNOOC-to-address-the-grievances-faced-by-the-Kingfisher-project-host-communities-in-Kikuube-district-1.pdf.

Within the Kingfisher area, the presence of such a large and active military force has created an atmosphere of fear and intimidation in which many are fearful to speak out.

As a chairman of a village from Buhuka said to Climate Rights International:

I’m afraid that the government can punish us because we spoke to NGOs. We need to be anonymous.72Climate Rights International interview with Vincent Yeno.

Those who are vocal can face harsh repercussions. For example, on May 27, 2024, seven environmental human rights defenders were violently arrested by armed police when sitting outside the Chinese Embassy in Kampala in an attempt to present a letter of protest to the Chinese Ambassador.73Front Line Defenders, “Seven Environmental activists brutally arrested, charged and released on police bail for protesting against the East African Crude Oil Pipeline Project,” statement, June 7, 2024, https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/statement-report/seven-environmental-activists-brutally-arrested-charged-and-released-police-bail

On June 5-6, 2024, three local chairmen from villages in the Kikuube district who had been involved in attempts to present a petition to Daqing Oil Company, a Kingfisher subcontractor, were arrested by the officer in charge of the Kaseeta police and a team of Kikuube district police. Another human rights defender, Julius Tumwiine, faced threats and judicial harassment from the police in Kikuube, which were seen surrounding his house on June 5, 2024, at a time when he was not home.74International Federation for Human Rights, “Uganda: Alarming crackdown on environmental and human rights defenders,” press release, June 7, 2024, https://www.fidh.org/en/issues/human-rights-defenders/uganda-alarming-crackdown-on-environment-and-human-rights-defenders.

In June 2024, Stephen Kwikiriza, an environmental observer with the Environmental Governance Institute, was abducted, interrogated, and tortured by the UPDF. Kwikiriza had documented the environmental devastation and human rights violations suffered by his community from the Kingfisher project.75Climate Rights International, “Uganda: Independent Investigation Needed for Abduction, Beating of EACOP Activist,” press release, June 11, 2024, https://cri.org/uganda-independent-investigation-needed-for-abduction-beating-of-eacop-activist/.

According to FIDH, Kwikiriza was one of 11 campaigners against oil projects who were targeted by Ugandan police, military or government officials over a two-week period in early June.76Sarah Johnson, “Ugandan oil pipeline protester allegedly beaten as part of ‘alarming crackdown,’” The Guardian, June 12, 2024.

Since his abduction, there has been a pervasive climate of fear among other activists in the Kingfisher region, some of whom have reported seeing what appear to be plainclothes military near their homes and offices.

In Kampala, 50 people were arrested on August 9 on their way to parliament to protest against the oil project, following the arrest a few days earlier of four environmental activists at the Chinese Embassy.77Busein Samilu, “Police arrest 50 individuals in foiled anti-Eacop protest”, Monitor, Aug. 9, 2024, https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/police-arrest-50-individuals-in-foiled-anti-eacop-protest-4720172.

The allegations in this report related to the Kingfisher project raise serious concerns about the practices of CNOOC and its subcontractors, as well as their compliance with Ugandan and international law, IFC performance standards, and the commitments that CNOOC and its partners have made. They also raise serious concerns about the actions of the Ugandan military, and the impunity with which it continues to act.

A full set of recommendations can be found at the end of this report in Chapter XVI.

This report is based on information collected during field research between January and July 2024. Climate Rights International interviewed 98 people, including 83 people residing in the Kingfisher oil project area, and five who had relocated in recent years due to the effects of the project. Nine others resided in Kikuube district along the feeder pipeline, outside the lakeshore/landing site. Except for three individuals interviewed together during a preliminary survey, all interviews were conducted individually. One additional interview was conducted with a researcher who has performed multiple studies in the area.

The interviews were primarily conducted in the languages of Alur, Swahili, Kinyarwanda, Runyoro, or English, with those not initially in English translated. Interviewees included fisherfolk, traders, farmers, shepherds, village chairmen, boda boda riders (motorcycle taxi drivers), and current or former employees of CNOOC or its subcontractors. Due to the high level of repression in the area and fears of retaliation by the UPDF, private companies, private security forces, oil and gas police, or regular police, pseudonyms have been used for all interviewees.

Interviews were conducted on a voluntary basis, with all participants fully informed about the purpose of the research. Participants were free to discontinue the interview at any point or decline to answer specific questions. No financial incentives were offered. Meal expenses and transportation costs (depending on the distance between the place of residence and the interview location) were reimbursed.

We also reviewed press articles, NGO reports, the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for the Kingfisher project, and other relevant documents related to the Kingfisher and the wider oil and gas activities.

The University of California, Berkeley, provided satellite imagery analysis to validate testimonies where feasible.

In October 2006 an Australia-based “wildcatter” petroleum company, Hardman Resources, made the first commercial oil discovery in Ugandan history on the eastern shores of Lake Albert between the small settlements of Kaiso and Tonya. Drilling deep into the Albertine Graben, a Mesozoic-Cenozoic rift basin into which thick sediments have accumulated over hundreds of millions of years, Hardman reported “good oil shows.”78Uchenna Izundu, “Hardman reports oil shows in Ugandan well,” Oil and Gas Journal, Nov. 16, 2006, https://www.ogj.com/exploration-development/article/17280550/hardman-reports-oil-shows-in-ugandan-well.

To announce and celebrate the discovery, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni convened a national prayer festival, during which he thanked God, “for having created for us a rift valley twenty-five million years ago,” and for providing “the wisdom and foresight to develop the capacity to discover this oil.”79Richard M Kavuma, “Great Expectations in Uganda over Oil Discovery,” Guardian, Dec. 2, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/katine/2009/dec/02/oil-benefits-rural-uganda.

Two other exploration oil companies were also present: Energy Africa and Heritage Oil, holding different permits in the area.80Directorate of Petroleum – Uganda – Petroleum Exploration History, https://petroleum.go.ug/index.php/who-we-are/who-weare/petroleum-exploration-history Hardman Resources was quickly acquired by Tullow Oil, a London-based multinational oil and gas exploration company, for $1.1 billion, giving it full control of one of three major permit blocks.81The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, “Oil in Uganda: Hard bargaining and complex politics in East Africa,” Dec. 2015, https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/WPM-601.pdf. Tullow Oil acquired the Energy Africa the same year.82Directorate of Petroleum – Uganda – Petroleum Exploration History, https://petroleum.go.ug/index.php/who-we-are/who-weare/petroleum-exploration-history

Between 2006 and 2010, more discoveries substantially increased the size of Uganda’s oil-yielding concessions and attracted a slate of international investors. After further assessment and drilling, the Ugandan government estimated that there were around 6.5 billion barrels of oil under Lake Albert, of which 1.4 billion barrels were determined to be recoverable.83Petroleum Authority of Uganda, Uganda’s Petroleum Resources website consulted on July 1, 2024. https://www.pau.go.ug/ugandas-petroleum-resources

In 2010, Tullow Oil acquired the other two permits when it purchased Heritage Oil’s assets in Uganda for $1.45 billion. In 2012 Tullow sold two-thirds of its interests to TotalEnergies and CNOOC “to accelerate development” of oil exploitation. The new consortium gave each company a one-third stake in each of the blocks.

CNOOC purchased its interest from Tullow for approximately $1.467 billion in cash and took charge of operating the Kingfisher development project (block EA3A).84CNOOC Limited, “Completion of Acquisition on Ugandan Assets”, 2012-02-21, https://www.cnoocltd.com/art/2012/2/21/art_8361_1669311.html. Tullow and TotalEnergies were respectively responsible for operating blocks EA2 and EA1. TotalEnergies acquired Tullow’s entire stake in April 2020.85TotalEnergies, “Total Acquires Tullow Entire Interests in the Uganda Lake Albert Project,” news release, Ap. 23, 2020, https://totalenergies.com/media/news/news/total-acquires-tullow-entire-interests-uganda-lake-albert-project. UNOC entered into the Production Sharing Agreements and the Joint Venture Agreements for EA1, EA2, and EA3 (Tilenga and Kingfisher developments) in April 2021.86Business Focus, “UNOC Explains Progress On Uganda’s Oil Exploration Projects,” Feb. 3, 2022, https://businessfocus.co.ug/unoc-explains-progress-on-ugandas-oil-exploration-projects/. Both Tilenga and Kingfisher are now jointly owned by TotalEnergies (56.67 percent), CNOOC (28.33 percent) and the Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC 15 percent).87Eoin O’Cinneide, “Tilenga & Kingfisher: Huge contracts near as Uganda and Tanzania agree key oil deals,” Upstream Online, Ap. 14, 2021, https://www.upstreamonline.com/field-development/tilenga-kingfisher-huge-contracts-near-as-uganda-and-tanzania-agree-key-oil-deals/2-1-993890.

Drilling rig at the Kingfisher project © Mathieu Ajar

Once processed at the Tilenga and Kingfisher Central Processing Facilities (CPF), the oil produced at these projects will be transported by the feeder pipelines to Kabaale, a town in Hoima district. There, at the Kabaale Industrial Park (currently under construction), the oil will be metered and then combined into a single stream. The government is seeking private partners to construct an oil refinery, which could refine up to 60,000 barrels per day (bpd) to serve domestic and regional markets.88Petroleum Authority of Uganda, “The Uganda Refinery Project,” https://www.pau.go.ug/the-uganda-refinery-project/. The majority of the oil, up to 246,000 bpd at peak production, will be exported to the international market with the EACOP.89East African Crude Oil Pipeline, “Overview,” https://www.eacop.com/overview/

Given Uganda’s status as a landlocked country and the remote location of its reserves – more than 700 miles (1,126 km) inland from the nearest major port in Mombasa, Kenya – the oil from the Tilenga and Kingfisher Projects can only be fully commercialized for the international market through construction of a massive pipeline to the coast.

In 2017, after long negotiations and the abandonment of a proposed Uganda-Kenya pipeline,90Global Energy Monitor Wiki, “Uganda-Kenya Crude Oil Pipeline (UKCOP),” https://www.gem.wiki/Uganda%E2%80%93Kenya_Crude_Oil_Pipeline_(UKCOP). the governments of Uganda and Tanzania agreed to develop the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP).91Kizito Makoye, “Uganda, Tanzania begin construction of key oil pipeline,” Aug. 5, 2017, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/uganda-tanzania-begin-construction-of-key-oil-pipeline/877028. In early 2022, the major stakeholders – TotalEnergies, CNOOC, UNOC, and the Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC) – reached a Final Investment Decision on the “Lake Albert Resources Development Project,” which encompasses both EACOP and the Tilenga and Kingfisher projects.92Pam Boschee, “TotalEnergies and CNOOC Announce FID for $10-Billion Uganda and Tanzania Project,” JPT75, Feb. 2, 2022, https://jpt.spe.org/totalenergies-and-cnooc-announce-fid-for-10-billion-uganda-and-tanzania-project. The parties committed to invest over $10 billion in the project.93TotalEnergies, Uganda and Tanzania: launch of the Lake Albert Resources Development Project, Feb 1, 2022. https://totalenergies.com/media/news/press-releases/uganda-and-tanzania-launch-lake-albert-resources-development-project.

The pipeline is intended to carry the crude oil from the Tilenga and Kingfisher projects almost 1,443 km from the refinery in Kabaale to the Chongoleani Peninsula near Tanga Port in on the Tanzanian coast.94East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline, “Overview,” https://eacop.com/. The route, 80 percent of which is in Tanzania, heads south 296 km from Kabaale through Uganda to the Tanzanian border. It tracks the western shore of Lake Victoria, before turning east and cutting through the heart of Tanzania’s northern savannahs and steppes toward the ocean.95East Africa Cruse Oil Pipeline, “Route Description and Map,” https://eacop.com/route-description-map/.

Main ecosystems under threat.96Friends of the Earth France and Survie, “A Nightmare Named Total,” report, Oct. 2020, https://www.amisdelaterre.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/a-nightmare-named-total-oct2020-foe-france-survie.pdf.

According to construction plans, EACOP will be a buried thermally insulated 24-inch pipeline. Due to the viscous and waxy nature of Uganda’s crude oil, the pipeline will need to be heated along the entire route, making the EACOP the longest heated crude oil pipeline in the world.97Ugandan National Oil Company, “East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline,” https://www.unoc.co.ug/midstream/east-african-crude-oil-pipeline/.

While the initial cost of the pipeline was estimated to be around $3.5 billion98Uganda: Museveni, Magufuli Lay Foundation Stone for Oil Pipeline”, The Independent, Aug. 6, 2017, https://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/index2.php?url=https%3A%2F%2Fallafrica.com%2Fstories%2F201708070048.html#federation=archive.wikiwix.com&tab=url. and was still officially stated as such during the signing of the Final Investment Decision in 2022,99“Uganda-Tanzania Crude Oil Pipeline Final Investment Decision Signed,” TanzaniaInvest, Feb, 8, 2022, https://www.tanzaniainvest.com/energy/eacop-final-investment-decision. its cost has significantly increased and is now estimated by authorities to be around $5 billion.100Ugandan Infrastructure administration website, “The EACOP Construction Budget Increases to $5 Billion”, Jan. 29, 2024, https://infrastructure.go.ug/the-eacop-construction-budget-increases-to-5-billion/. The ownership of the pipeline is divided among four entities: TotalEnergies, which owns 62 percent; the Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC) at 15 percent; the Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC) at 15 percent; and CNOOC Uganda Limited at 8 percent.101Christopher E. Smith, “Uganda approves EACOP, construction to start late 2023,” Oil and Gas Journal, Jan. 20, 2023. https://www.ogj.com/pipelines-transportation/pipelines/article/14288579/uganda-approves-eacop-construction-to-start-late-2023. The pipeline’s operations are managed by EACOP Ltd., a company incorporated in the United Kingdom and which has the same shareholding structure as the pipeline.102Companies House, East African Crude Oil Pipeline Ltd., https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/11298396.

The Tilenga project is situated in the Buliisa and Nwoya districts along the northeast shore of Lake Albert and is managed by TotalEnergies EP Uganda, a wholly owned subsidiary of TotalEnergies.103TotalEnergies, Universal Registration Document 2023, p. 511, https://totalenergies.com/system/files/documents/2024-03/totalenergies_universal-registration-document-2023_2023_en_pdf.pdf#page=511. It consists of six oil fields and will include over 400 wells from 31 drilling pads; 160 km of pipeline networks to manage the flow of oil, water, and gas; construction of a Central Processing Facility to separate and treat the oil, water, and gas produced by the wells; and a 95 km feeder pipeline from the Central Processing Facility to a proposed refinery in Kabaale.104Petroleum Authority of Uganda, “The Tilenga Project,” https://www.pau.go.ug/the-tilenga-project/. It is expected to produce around 204,000 barrels per day (bpd).105East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline, “Overview,” https://eacop.com/overview/.

Crucially, a significant part of the Tilenga project’s activities is located within Uganda’s oldest and most visited natural reserve, the Murchison Falls National Park. This park is home to several endangered species, including the Rothschild’s giraffe and the Uganda Kob. Other notable species include the African elephant, lion, leopard, hippo, and chimpanzee. Additionally, it hosts over 450 species of birds, some of which are in danger of extinction.106Andrew Plumptre, et al., “Biodiversity surveys in Murchison Falls Protected Area,” Jan. 2015, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283122588_Biodiversity_surveys_of_Murchison_Falls_Protected_Area. 132 oil wells will be drilled inside this park (and potentially 39 other oil wells at a later date, still in the park).107https://totalenergies.com/sites/g/files/nytnzq121/files/documents/2021-03/Tilenga_esia_non-tech-summary_28-02-19.pdf#page=63. A map of the 10 JBR well pads (JBR-1 to JBR-10) shows that they are located in the park: ESIA of Tilenga, volume 1, Feb. 2019, p. 4-6 (190), https://totalenergies.ug/tilenga-project-environmental-and-social-impact-assessmente-esia-report, p.4-19 (203).

TotalEnergies construction work to prepare a drilling site in Murchison Falls National Park © Thomas Bart

A July 2023 Human Rights Watch report with interviews with 75 displaced families in five districts of Uganda concluded that the Tilenga project had led to “devastating impacts on livelihoods of Ugandan families from the land acquisition process.” In particular, Human Rights Watch found that, “The land acquisition process has been marred by delays, poor communication, and inadequate compensation. … Affected households are much worse off than before. Many interviewees expressed anger that they are still awaiting the adequate compensation promised by TotalEnergies and its subsidiaries in early meetings in which company representatives extolled the virtues of the oil development. Families described pressure and intimidation by officials from TotalEnergies EP Uganda and its subcontractors to agree to low levels of compensation that was inadequate to buy replacement land. Most of the farmers interviewed from the EACOP pipeline corridor, many of them illiterate, said that they were not aware of the terms of the agreements they signed. Those who have refused signing described facing constant pressure from company officials, threats of court action, and harassment from local government and security officials.”108Human Rights Watch, “Our Trust is Broken: Loss of Land and Livelihoods for Oil Development in Uganda,” report, July 10, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/07/10/our-trust-broken/loss-land-and-livelihoods-oil-development-uganda.

A November 2023 follow-up report found that activists and opponents of EACOP in Uganda faced arbitrary arrests, threats, and harassment for protesting the Tilenga project.109Human Rights Watch, “Working on Oil is Forbidden: Crackdown Against Environmental Defenders in Uganda,” report, Nov. 2, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/11/02/working-oil-forbidden/crackdown-against-environmental-defenders-uganda.

The Kingfisher project consists of a single oil field, with plans for 31 wells, 19 kilometers of flowlines, a central processing facility, and other facilities. It is located on Block 3A (south of the Tilenga project) on the long southeastern shore of Lake Albert in Kikuube district.

Kingfisher is operated by CNOOC and is expected to produce 40,000 barrels per day.110Petroleum Authority of Uganda, “The Kingfisher Development Project,” https://www.pau.go.ug/the-kingfisher-development-project/. In January 2023, CNOOC Uganda officially began drilling for oil at Kingfisher, with production expected to commence in 2025.111“Uganda launches first oil drilling programme, targets 2025 output,” Al Jazeera, Jan. 24, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/1/24/uganda-to-unveil-first-commercial-oil-production-drilling-programme; Petroleum Authority of Uganda, “Uganda launches drilling activities for the Kingfisher project,” news release, Jan. 25, 2023, https://www.pau.go.ug/uganda-makes-big-stride-towards-first-oil.

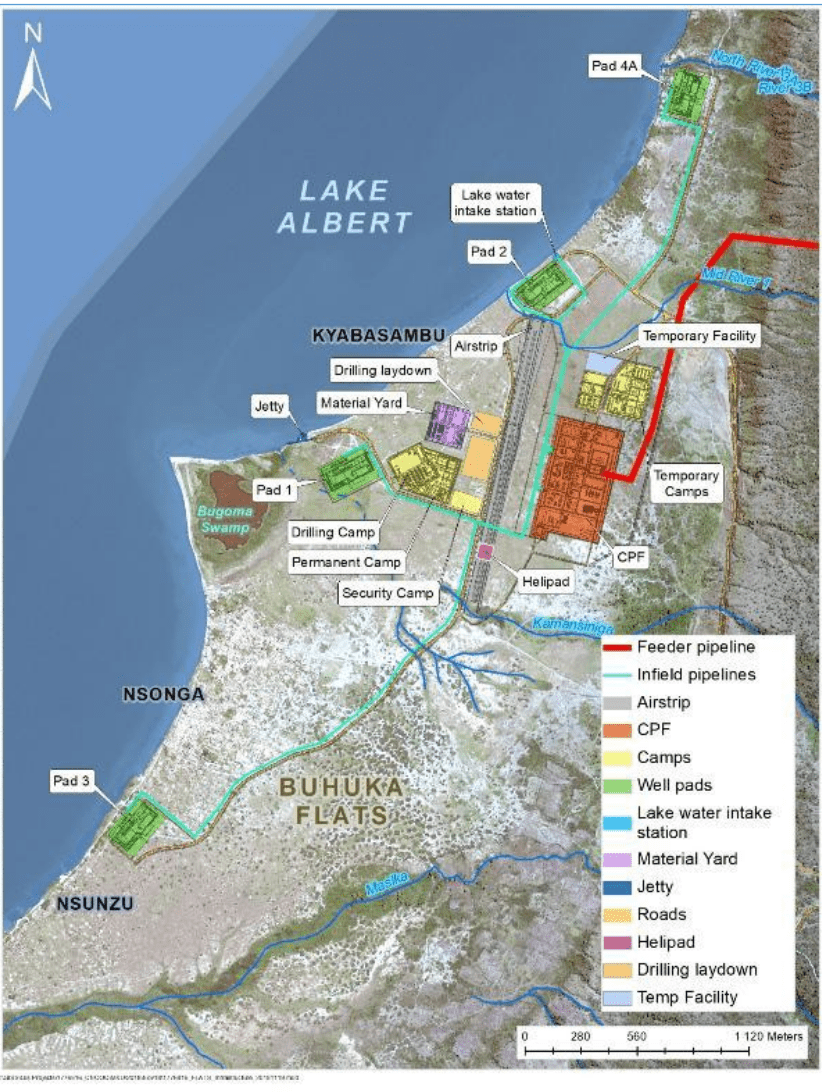

The “Kingfisher Development Area” lies along the eastern shore of Lake Albert. CNOOC’s ESIA states that the project is located on a field “approximately 15.2 km long by 3.0 km wide.”112CNOOC Uganda Limited, Kingfisher ESIA Report, volume 4, study 1. Nov 2019. p. 1 (11), https://www.eia.nl/projectdocumenten/00006432.pdf#page=11 The project infrastructure is located in two areas. The primary area is along the shores of Lake Albert on a flat area of land between the escarpment and the lake in Buhuka Parish in an area called Buhuka Flats. The second area follows the 52 kilometer feeder pipeline and passes through six sub-counties, from the Buhuka CPF to Kabaale, where the EACOP pipeline begins its route to Tanzania.113CNOOC Uganda Limited, Kingfisher ESIA Non-Technical Executive Summary, Sept. 2018, p. 40 (48). https://nema.go.ug/sites/all/themes/nema/docs/Vol_0_CNOOC_Kingfisher_ESIA_Non-Technical_Summary_Final.pdf#page=48.

The majority of the Kingfisher project’s infrastructure is located along the Lake Albert shoreline, within or near seven villages: Kyabasambu, Kyakapere, Nsonga A, Nsonga B, Nsunzu A, Nsunzu B, and Kiina, all situated in the Buhuka Flats. Additionally, the ESIA indicates that six other villages, still on the lake’s shoreline, are also potentially affected by the project, namely: Busigi, Kyenyanja, Ususa, Kacunde, Senjojo, and Sangarao, all of which neighbor the Buhuka Flats to the north and south.

The main facilities of the Kingfisher project include:

CNOOC ESIA November 2019: Layout of the project on the Buhuka Flats114CNOOC Uganda Limited, ESIA Kingfisher Report Volume 1, November 2019, p.2-3 (66) https://www.eia.nl/projectdocumenten/00006434.pdf#page=66

The feeder pipeline that will connect the Central Processing Facility (CPF) located at Buhuka to Kabaale, where the oil refinery project and the starting point of the pipeline are situated, will also impact residents of an additional 24 villages.115CNOOC Uganda Limited, Kingfisher ESIA Report Volume 4C Physical Environment, November 2019, p. 73 (94) https://www.eia.nl/projectdocumenten/00006430.pdf#page=94.

Location of villages and estimated village size along the feeder pipeline route.116CNOOC Uganda Limited, Kingfisher ESIA Report – Non-Technical Summary, September 2018. p. 40, https://nema.go.ug/sites/all/themes/nema/docs/Vol_0_CNOOC_Kingfisher_ESIA_Non-Technical_Summary_Final.pdf#page=48.

Clan, communal land, and individual ownership under customary tenure is the dominant form of land tenure in Uganda, covering 75 percent of the nation’s total land. This typically involves land owned and managed by individual families or clans, with rights inherited and passed down through generations.

The Constitution of the Republic of Uganda and Ugandan law provide extensive protection for property rights. Article 237 of the Constitution provides that land belongs to the citizens in accordance with the legally mandated land tenure systems. It states that, “(1) Land in Uganda belongs to the citizens of Uganda and shall vest in them in accordance with the land tenure systems provided for in this Constitution. […] (3) Land in Uganda shall be owned in accordance with the following land tenure systems – (a) customary; (b) freehold; (c) mailo; and (d) leasehold.”

Article 26(1) of the Ugandan Constitution explicitly guarantees the right of individuals to own property either individually or in association with others.117Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, 1995, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/ug/ug023en.pdf. Article 26(2) of the Constitution provides that, “No person shall be compulsorily deprived of property or any interest in or right over property of any description except where the following conditions are satisfied – (a) the taking of possession or acquisition is necessary for public use or in the interest of defence, public safety, public order, public morality or public health; and (b) the compulsory taking of possession or acquisition of property is made under a law which makes provision for – (i) prompt payment of fair and adequate compensation, prior to the taking of possession or acquisition of the property; and (ii) a right of access to a court of law.”118Ibid.

The 1998 Land Act also requires that any decisions regarding the compulsory acquisition of land include adequate compensation, and that such compensation is to be paid promptly before displacement.119Laws of Uganda, The Land Act 1998, https://mlhud.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Land-Act-1998-as-amended-CAP-227.pdf. The requirement of prior compensation is consistent with and reinforced by decisions by the Ugandan Constitutional Court.120See Irumba Asumani, Peter Magelah vs. Attorney General Uganda and National Roads Authority, Constitutional Petition No. 40 of 201, https://ulii.org/akn/ug/judgment/ugsc/2015/22/eng@2015-10-29 (finding section 7, paragraph 1 of the Land Acquisition Act to violate Article 26(2) of the Constitution of Uganda to the extent that the law does not provide for prior payment of compensation before the government compulsorily acquires or takes possession of any person’s property).

Mirroring the Constitution, the Land Act recognizes four major types of tenure: customary, freehold, leasehold and mailo.121Laws of Uganda, The Land Act 1998, Act 16, art. 3, https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/uga19682.pdf. For a presentation of the four land tenures in Uganda, see: Nampwera Chrispus “Uganda’s land tenure systems and their impact on development”, Makerere Law Journal, Oct. 2022, https://www.academia.edu/91848426/ugandas_land_tenure_systems_and_their_impact_on_development. The Land Act acknowledges that parcels of land within customary land may be recognized as subdivisions belonging to a person, a family or a traditional institution.122Laws of Uganda, The Land Act 1998, Act 16, art. 4(1)(g). https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/uga19682.pdf.

The Ugandan National Land Policy (NLP), issued in 2013, noted that despite the efforts of the Constitution and the Land Act to formalize customary tenure, it “continues to be regarded and treated as inferior in practice to other forms of registered property rights.”123Uganda Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development, “The Uganda National Land Policy”, February 2013, section 4.3, https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/uga163420.pdf#page=24The Land Policy called for the government to recognize customary land on a par with other forms of tenure and to establish a land registry system for registration of land rights under customary tenure.124Ibid, section 39, 40(a). Regrettably, the legal and policy framework safeguarding customary tenure has so far remained largely unimplemented.

The predominant norm within Buhuka Flats is communal land ownership, governed by customary tenure. This is characterized by the collective management and utilization of land, with community members sharing access to resources such as grazing areas and water sources.125CNOOC Uganda Ltd., Kingfisher ESIA, Study 10: Socio-Economic Assessment, June 2018, page 72. This system is deeply embedded in the cultural practices of the communities.

However, claims of ownership often face challenges due to the lack of formal land titles, leading to vulnerabilities in land security. As noted in a policy brief by Avocats Sans Frontières, communal land is often regarded as “open access territory,” whereby “everybody, and thus nobody, owns the land. Indeed, it largely exposes it to land grabbers, especially in the context of the extractive industries boom, with the passive – and sometimes active – collusion of non-diligent [local government] officials.”126Avocats Sans Frontières, Anardé, and CRED, “Enhancing legal protection of communities affected by extractive industries in Uganda,” policy brief, Aug. 2020, p.3, https://www.asf.be/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/PolicyBriefExtractiveIndustriesUganda.pdf.

It should be noted that the provisions of IFC’s PS5 apply equally to communal lands and the communities living on them, as they do to individuals owning private lands.127IFC, Performance Standard 5 about Land Acquisition and Involuntary Resettlement, p. 2, https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2010/2012-ifc-performance-standard-5-en.pdf.

The Ugandan Employment Act of 2006 is the primary law governing conditions of employment. The law requires all employment relationships to be formalized with a written contract detailing the terms and conditions of employment. In addition, it stipulates that employees are entitled to 24 consecutive hours of rest each week. This day of rest can be on any day of the week.128Uganda Employment Act, 2006, sec. 51 https://ulii.org/akn/ug/act/2006/6/eng%402006-06-08. The law also imposes a maximum work limit, not exceeding ten hours per day or fifty-six hours per week.129Ibid, sec. 53.

Section 7 of the Employment Act defines sexual harassment:

An employee shall be sexually harassed in that employee’s employment if that employee’s employer, or a representative of that employer – (a) directly or indirectly makes a request of that employee for sexual intercourse, sexual contact or any other form of sexual activity that contains – (i) an implied or express promise of preferential treatment in employment; (ii) an implied or express threat of detrimental treatment in employment; (iii) an implied or express threat about the present or future employment status of the employee.130Ibid., sec. 7.

Uganda’s Occupational Safety and Health Act, 2006, obliges employers to ensure the health, safety, and welfare of all persons at the workplace, and to have first aid available in the event of a work accident.131Occupational Safety and Health Act, 2006 Act 9 of 2006 https://ulii.org/akn/ug/act/2006/9/eng@2006-06-08.

The Workers Compensation Act requires employers to provide compensation to employees for work-related injuries that “(a) result in permanent incapacity; or (b) incapacitate the worker for at least three consecutive days from earning full wages at the work at which he or she was employed.”132The Workers Compensation Act, 2000, https://ira.go.ug/cp/uploads/Workers%20Compensation%20Act%20Cap%20225.pdf, sec. 3. Under section 11 of that act, the employer is required to arrange to have the employee examined by a qualified medical practitioner “at no charge to the worker,” and to pay the cost of medical expenses during any period of temporary incapacity.133Ibid., sec. 11, 24.

The Ugandan government has established specific legislation for the management of oil waste in The Petroleum (Waste Management) Regulations.134The Petroleum (Waste Management) Regulations, 2019, https://nema.go.ug/sites/all/themes/nema/docs/Petroleum%20(Waste%20Management)%20Regulations%20S.I.%20No.%203%20of%202019.pdf. Its objectives include “(a) to prevent harm to human health and ensure safety of human beings; (b) to prevent pollution, harm to biological diversity and contamination of the wider environment by petroleum waste; (c) to use the best available technologies and best environmental practices.”135Ibid, article 4.

An Environmental and Social Impact Assessment is a legal requirement in most, if not all, countries before major infrastructure projects are undertaken. An ESIA process must consider all stages of the development process, including the construction of the facility, site operations, the dismantling and decommissioning of the site, and site restoration. In certain situations, however, the proponent may also be required to, or choose to, comply with certain international standards. Typically, this is required where international funding is sought to support the development of the project. In some circumstances, however, proponents may choose to demonstrate compliance with international standards on their own volition.