Aerial view of Tokyo by Arto Marttinen via Unsplash

“Sometimes I feel like my whole body is shaking and I also feel dizzy when I perform physical labor [in the heat] like washing cars. I also get tired easily, but I have to work because if I don’t, I won’t earn a living.” — A man who washes cars in Karachi1CRI interview with Muhammad Yusuf, Karachi, Pakistan, September 13, 2023.

The acceleration of global warming has resulted in rising temperatures and an unprecedented frequency, intensity, and duration of heat waves worldwide, creating a human rights crisis that all levels of governments, companies, and others with responsibility for the health and welfare of human beings must take urgent steps to address.

This report examines the consequences and risks of extreme heat through a human rights lens and offers concrete recommendations for actions that can be taken – starting now – to protect populations from harm. Climate Rights International compiled this report to identify and understand the many different rights that are put at risk by rising temperatures and exposure to extreme heat as a result of climate change. Viewing climate change through a human rights lens can help identify actionable solutions, and the responsibilities of governments, companies, and others to act.

People around the world, both old and young, are at risk of experiencing heat-related harms. As Aprdous Hossain, a 74-year-old widow in Dhaka, Bangladesh, which now regularly experiences days with temperatures exceeding 40°C (104°F), told Climate Rights International:

I feel very bad this year because of the heat. I am feeling very bad, very sick, I am not feeling well. Because I am too hot. I cannot cool.2CRI interview with Muhammad Talha, Karachi, Pakistan, Sept. 13, 2023.

A nine-year-old student in Karachi, which suffers from frequent heat waves, told Climate Rights International that the heat made it hard to learn:

I feel like I am not able to study properly or concentrate because the classroom is so hot, and all of the kids are so tired because of the heat. We are not able to learn or pay attention to what the teacher is saying because of that.3CRI interview with Hania Saud, Karachi, September 2023.

Dr. Aliya Saidi, a doctor in Karachi, explained the kinds of cases she is seeing:

Patients come to us with various symptoms of heat-related illness. These include excessive sweating, low blood pressure, panting, dizziness, restlessness, vomiting, muscle ache, headache, and exhaustion.4CRI interview with Aliya Zaidi, Karachi, Pakistan, September 15, 2023.

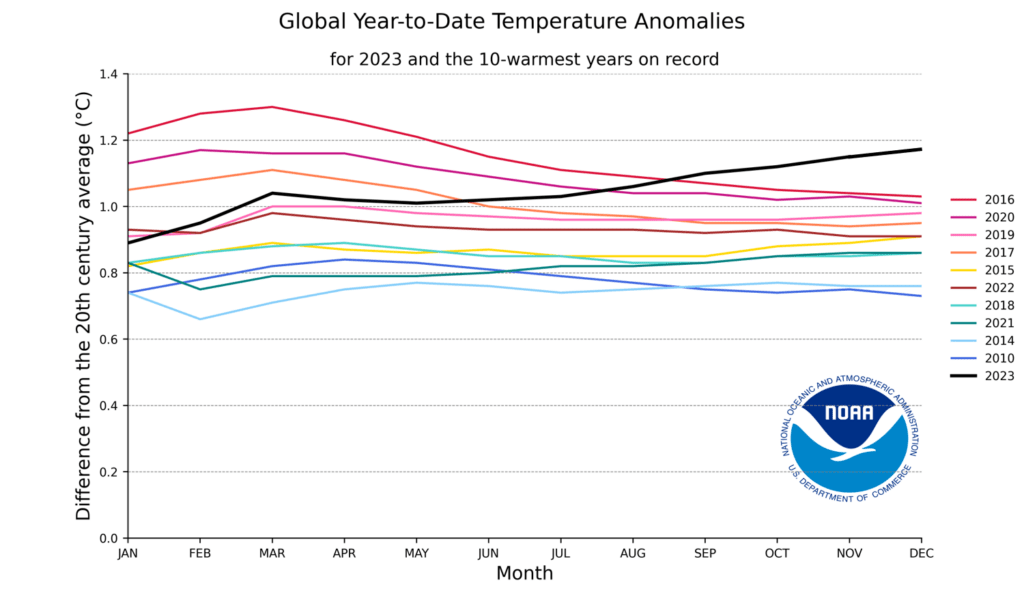

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has confirmed that 2023 was the hottest year on record.5 World Meteorological Organization, “WHO confirms that 2023 smashes global temperature record,” press release, Jan. 12, 2024. The WMO consolidated six leading international datasets used for monitoring global temperatures and determined that the annual average global temperature was 1.45 ± 0.12 °C above pre-industrial levels (1850-1900) in 2023. This record marks an unfortunate trend of rising global averages, as the last nine years have been the hottest ever recorded; and each of those years experienced global averages more than 1°C (1.8°F) above the preindustrial level.6World Meteorological Organization, “2023 shatters climate with major impacts,” November 30, 2023, https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/2023-shatters-climate-records-major-impacts#:~:text=The%20past%20nine%20years%2C%202015,global%20temperatures%20after%20it%20peaks.

Freedman, A. “The past 8 years were the world’s warmest, report finds,” Axios, January 10, 2023, https://www.axios.com/2023/01/10/climate-change-warmest-year. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the authoritative body on climate science, has indicated with high confidence that human-induced climate change is the main driver of the increase in average temperatures in recent history.7Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report, “Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Summary for Policy Makers,” https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SPM_final.pdf.

Human-induced climate change also plays a major role in heat waves.8Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report, “Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Summary for Policy Makers,” https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SPM_final.pdf. While there is no standard definition for a heat wave, or extreme heat event, the term is used to describe prolonged periods of extreme heat outside the normal range of temperatures for a certain region. The World Weather Attribution (WWA) initiative has found that many heat waves in recent history were made much more likely by climate change.9Because climate attribution science is a relatively new and growing field, there is an ongoing debate about the methods and limitations of this work. More about WWA’s considerations here: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-021-03071-7 For example, the WWA found that the April heat wave that devastated much of Asia in 2023, causing deaths, widespread hospitalizations, and school closures, was made 30 times more likely by climate change.10World Weather Attribution, “Extreme humid heat in South Asia in April 2023, largely driven by climate change, detrimental to vulnerable and disadvantaged communities,” May 17, 2023, https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/extreme-humid-heat-in-south-asia-in-april-2023-largely-driven-by-climate-change-detrimental-to-vulnerable-and-disadvantaged-communities/. It also found that a deadly heatwave in the Sahel and Western Africa in March and April 2024 “would not have occurred” in the absence of human-induced climate change,11World Weather Attribution, “Extreme Sahel heatwave that hit highly vulnerable population at the end of Ramadan would not have occurred without climate change,” Apr. 18, 2024, https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/extreme-sahel-heatwave-that-hit-highly-vulnerable-population-at-the-end-of-ramadan-would-not-have-occurred-without-climate-change/. and that the devastating heat wave in western North America in June 2022 would have been “virtually impossible” without it.12Sjoukje, et al. “Rapid attribution analysis of the extraordinary heatwave on the Pacific Coast of the US and Canada June 2021,” World Weather Attribution, https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/wp-content/uploads/NW-US-extreme-heat-2021-scientific-report-WWA.pdf

A recent study found that between 2018 and 2022 people globally experienced, on average, 86 days of health-threatening high temperatures annually.13Romanello, et al. “The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: the imperative for a health-centered response in a world facing irreversible harms,” The Lancet, November 2023, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(23)01859-7/fulltext, figure 2. Sixty percent of these temperatures were made more than twice as likely to occur by human-caused climate change.14Romanello, et al. “The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: the imperative for a health-centered response in a world facing irreversible harms,” The Lancet, November 2023, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(23)01859-7/fulltext.

NOAA graphic depicting the 10-warmest years on record (1850-2022), and 2023, which had the highest global land and ocean temperature for January–December in the 1850–2023 record.15NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, Monthly Global Climate Report for Annual 2023, published online January 2024, retrieved on May 1, 2024 from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global/202313/supplemental/page-1.

Extreme heat and extreme heat events threaten a wide range of human rights, including the rights to life, health, food, water, education, and a healthy environment. Those most at risk include children, women, older people, those with disabilities, those living in poverty, outdoor workers, and a range of already marginalized populations.16Sanz-Barbero B, Linares C, Vives-Cases C, González JL, López-Ossorio JJ, Díaz J. Heat wave and the risk of intimate partner violence. Sci Total Environ. 2018 Dec 10;644:413-419. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.368. Epub 2018 Jul 6. PMID: 29981991.

Some groups, including children, chronically ill people, older people, and those on certain medications, can be biologically more susceptible to the impacts of extreme heat than others.17Syed S, O’Sullivan TL, Phillips KP. Extreme Heat and Pregnancy Outcomes: A Scoping Review of the Epidemiological Evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):2412. doi:10.3390/ijerph19042412; Global Heat Health Information Network, “Heat & Health,” (2022), available via: https://ghhin.org/heat-and-health/ (accessed December 1, 2022). Other groups, such as women, incarcerated people, migrants, people living in poverty, and people living in social isolation, can be more vulnerable to the impacts of extreme heat as a result of social factors.18Zottarelli LK, Sharif HO, Xu X, Sunil TS. Effects of social vulnerability and heat index on emergency medical service incidents in San Antonio, Texas, in 2018. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75(3):271-276. doi:10.1136/jech-2019-213256; Kim Y ook, Lee W, Kim H, Cho Y. Social isolation and vulnerability to heatwave-related mortality in the urban elderly population: A time-series multi-community study in Korea. Environment International. 2020;142:105868. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2020.105868; Skarha J, Peterson M, Rich JD, Dosa D. An Overlooked Crisis: Extreme Temperature Exposures in Incarceration Settings. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(Suppl 1):S41-S42. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305453

Outdoor workers and those working in factories or other indoor spaces not designed for heat are also at increased risk because of their comparatively high levels of exposure to elevated temperatures. The International Labor Organization (ILO) recently estimated that at least 2.1 billion workers each year are exposed to excessive heat in the workplace, resulting in millions of occupational injuries and nearly 19,000 deaths.19International Labor Organization, “Ensuring Safety at Work in a Changing Climate,” report, 2024, https://www.ilo.org/publications/ensuring-safety-and-health-work-changing-climate.

People living in cities, too, face increased risk of exposure to high temperature extremes, in part due to the urban heat island effect, wherein some areas of cities absorb and retain heat more than surrounding areas due to dense concentrations of pavement, buildings, and other urban features. Researchers have documented more than 6°C (10°F) differences between some urban neighborhoods and surrounding rural areas in both high- and low-income countries.20Mentaschi, L., Duveiller Bogdan, G.H.E., Zulian, G., Corban, C., Pesaresi, M., Maes, J., Stocchino, A. and Feyen, L., Global long-term mapping of surface temperature shows intensified intra-city urban heat island extremes, GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE-HUMAN AND POLICY DIMENSIONS, ISSN 0959-3780, 72, 2022, p. 102441, JRC123644; How Post Reporters Mapped India’s Hottest Neighborhoods, The Washington Post, September 26, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/video/climate-environment/how-post-reporters-mapped-indias-hottest-neighborhoods/2023/09/26/fcd4c8a0-adcd-4cd4-93ad-e09b1a7fb880_video.html. Urban heat exposure has increased significantly in recent history. One study that assessed data from more than 13,000 cities around the world found that urban heat exposure increased nearly 200 percent between 1983 and 2016.21Cascade Tuholske, Kelly Caylor, Chris Funk and Tom Evans, “Global Urban Population Exposure to Extreme Heat,” Oct. 4, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.202479211. By 2050, 68 percent of the global population is expected to live in urban areas.22United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “68% of the world population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, says UN,” news release, May 16, 2018, https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html As the urban population increases, so too will the number of people exposed to increased risk of high temperature extremes.

Across all groups, heat impacts will weigh the heaviest on the poorest populations with the fewest resources to adapt. Locally, low-income residents often have greater levels of heat exposure and can be more likely to experience heat-stress.23Arifwidodo SD, Chandrasiri O. Urban heat stress and human health in Bangkok, Thailand. Environ Res. 2020 Jun;185:109398. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109398. Epub 2020 Mar 19. PMID: 32203732; Min, Jy., Lee, HS., Choi, YS. et al. Association between income levels and prevalence of heat- and cold-related illnesses in Korean adults. BMC Public Health 21, 1264 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11227-4; Hsu, A., Sheriff, G., Chakraborty, T. et al. Disproportionate exposure to urban heat island intensity across major US cities. Nat Commun 12, 2721 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22799-5 Globally, heat exposure over the last decade was more than 40% higher in countries in the lowest-quartile by income compared to the highest-quartile.24Alizadeh, M. R., Abatzoglou, J. T., Adamowski, J. F., Prestemon, J. P., Chittoori, B., Akbari Asanjan, A., & Sadegh, M. (2022). Increasing heat-stress inequality in a warming climate. Earth’s Future, 10, e2021EF002488. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EF002488 People in these low-income countries will face greater challenges adapting to rising temperatures than those in high-income countries, in part due to unequal access to cooling. A study by Sustainable Energy for All, an initiative launched by the United Nations in 2011, found that that one in seven people globally (1.2 billion people) do not have adequate access to cooling – threatening their ability to survive extreme heat, store nutritious food, or receive a safe vaccine.25Sustainable Energy for All, “Chilling Prospects: Tracking Sustainable Cooling for All 2022, report, https://www.seforall.org/chilling-prospects-2022/global-access-to-cooling-gaps#1. The nine countries with the largest number of people at high heat-related risk due to inadequate access to cooling are India, China, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Mozambique, Sudan, and Brazil.26Ibid.

The intersecting climate and human rights crises are going to become progressively more challenging. Global temperatures are likely to continue to surge – fueled by record levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases, deforestation, and periodic and naturally occurring El Niño events.27World Meteorological Organization, “Global temperatures set to reach new records in next five years,” press release, May 17, 2023, https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/global-temperatures-set-reach-new-records-next-five-years. Studies and models project that average global temperatures will reach or exceed 1.5°C (2.7°F) of warming much more rapidly than initially predicted and that levels of warming will likely be much higher than 1.5ºC if countries do not increase – and proactively implement – their commitments under the Paris Agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.28IPCC, 2023: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 1-34, doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.001 Without urgent and effective action, significant areas of the world are likely to become simply uninhabitable, resulting in widespread mortality, large-scale human migration, or both.29Lyon, C., et al. (2022). Climate change research and action must look beyond 2100. Global Change Biology, 28, 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15871

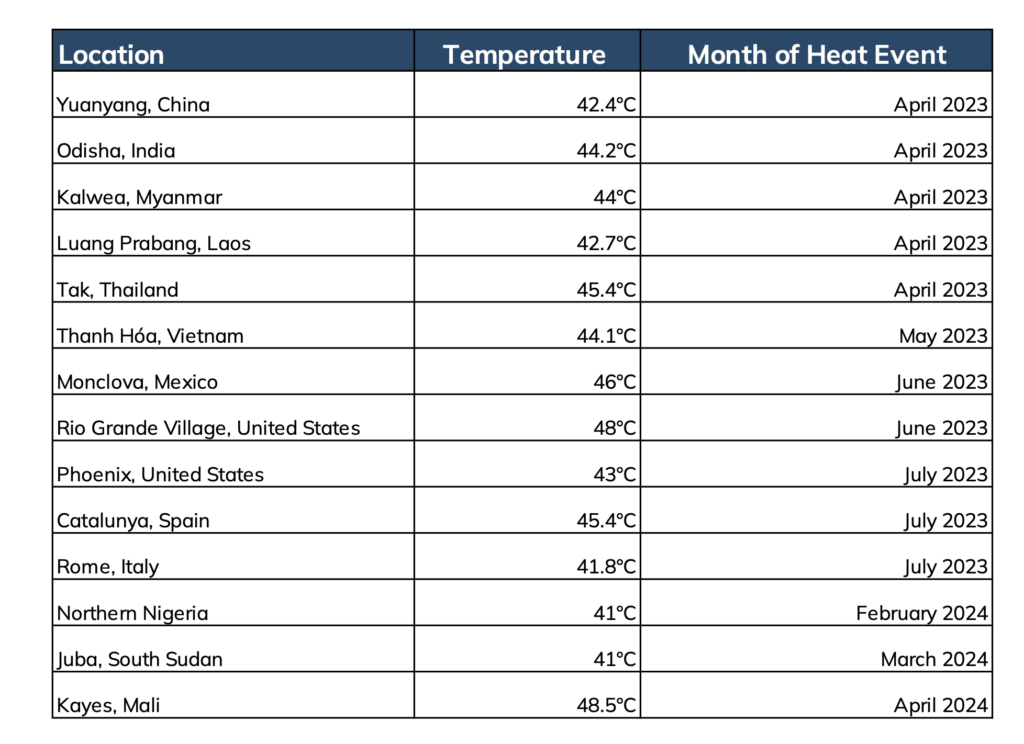

Recent extreme heat events.30Climate change: Vietnam records highest-ever temperature of 44.1C. (May 7, 2023). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-65518528 Extreme heat in North America, Europe and China in July 2023 made much more likely by climate change. (July 25, 2023). World Weather Attribution. https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/extreme-heat-in-north-america-europe-and-china-in-july-2023-made-much-more-likely-by-climate-change/ Extreme Sahel heatwave that hit highly vulnerable population at the end of Ramadan would not have occurred without climate change. (April 18, 2024). World Weather Attribution. https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/extreme-sahel-heatwave-that-hit-highly-vulnerable-population-at-the-end-of-ramadan-would-not-have-occurred-without-climate-change/ Gray, J. (June 26, 2023). Deadly Texas heat is spreading, and it will only get hotter. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2023/06/26/weather/heat-texas-records-south-monday/index.html Agence France-Presse in Hanoi, (May 7, 2023). Vietnam records highest ever temperature of 44.1C. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/may/07/vietnam-records-highest-ever-temperature-of-441c Lakhani, N. (2023, August 13, 2023). Heat deaths surge in the US’s hottest city as governor declares statewide ‘heat emergency’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/aug/13/phoenix-heat-tsar-cooling-shelters-heatwaves?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other Mandil, N., Chibelushi, W., and Taylor, M. (March 18, 2024). South Sudan heatwave: Extreme weather shuts schools and cuts power. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-68596499 Ward, T. and Regan, H. (April 19, 2023). Large swathes of Asia are sweltering through record breaking temperatures. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2023/04/19/asia/asia-heat-records-intl-hnk/index.html Stillman, D. (June 7, 2023). Tandon, A. (March 21, 2024). Climate change made west Africa’s ‘dangerous humid heatwave’ 10 times more likely. CarbonBrief. https://www.carbonbrief.org/climate-change-made-west-africas-dangerous-humid-heatwave-10-times-more-likely/

Governments have an obligation under international law to protect individuals against the foreseeable risks to their human rights due to extreme heat, including those caused by third parties such as businesses. Businesses, too, have an obligation to avoid infringing on the human rights of others, and to address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved.

To prevent worst-case outcomes, it is critical that governments redouble their efforts to drastically reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, particularly those from the burning of fossil fuels, protect carbon sinks, and invest in renewable energy.

At the same time, it is also critically necessary that governments, companies and those with responsibility for vulnerable populations implement heat-specific adaptation interventions to protect those under their care or control from the real risks to their human rights that will result from unavoidable heat extremes. Heat waves are already threatening and will increasingly threaten the health, environment, education, water, food, housing, and livelihoods of those alive today — and of future generations. In many areas, and for vulnerable groups, these risks will be truly life-threatening.

There is a large and growing body of knowledge regarding the steps that can be taken by governments (national, regional, and local), by companies and other employers, and by those running care homes, schools, prisons, and other institutional settings to reduce the risks posed by extreme heat to people. Yet many remain woefully unprepared, and failure to act will have devastating consequences for those they should be protecting.

A full set of detailed recommendations is available in Chapter VI.

This report is informed by a combination of literature review and primary research.

Climate Rights International conducted a narrative review of the existing literature on heat and related harms through May 2024. We searched PubMed, Embase, NexisUni, PAIS Index and Google Scholar for peer-reviewed academic papers and reviewed citations of selected articles when necessary. We also reviewed relevant grey literature, including policy documents, media publications, and NGO reports.

CRI also conducted interviews with some of those affected by extreme heat. We interviewed nine people living in Dhaka, Bangladesh between June 10 and July 8, 2023, and eleven people living in Karachi, Pakistan, between September 13 and September 15, 2023. Interviewees included ten women, six men and four children. We also spoke with individuals working on issues related to heat at a range of international organizations.

All interviewees provided informed consent to participate in the interview. In some cases, we have given pseudonyms and withheld identifying information of interviewees at their request or, for children, at the request of their parent or guardian. No financial incentives were provided to interviewees.

Extreme heat can lead to violations of a wide range of human rights, including the rights to life, health, food, water, education, and a safe and healthy work environment, among others. The warming of the planet is also a significant threat to the rights of future generations. The substance of each of these rights, and the ways in which extreme heat can lead to violations of these rights, is discussed below.

Climate change poses a serious threat to both physical and mental health. According to the IPCC, increases in extreme heat events in all regions of the world have led to increased human illness and death.31IPCC AYR 6 Synthesis Report, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/, para. A.2.5.

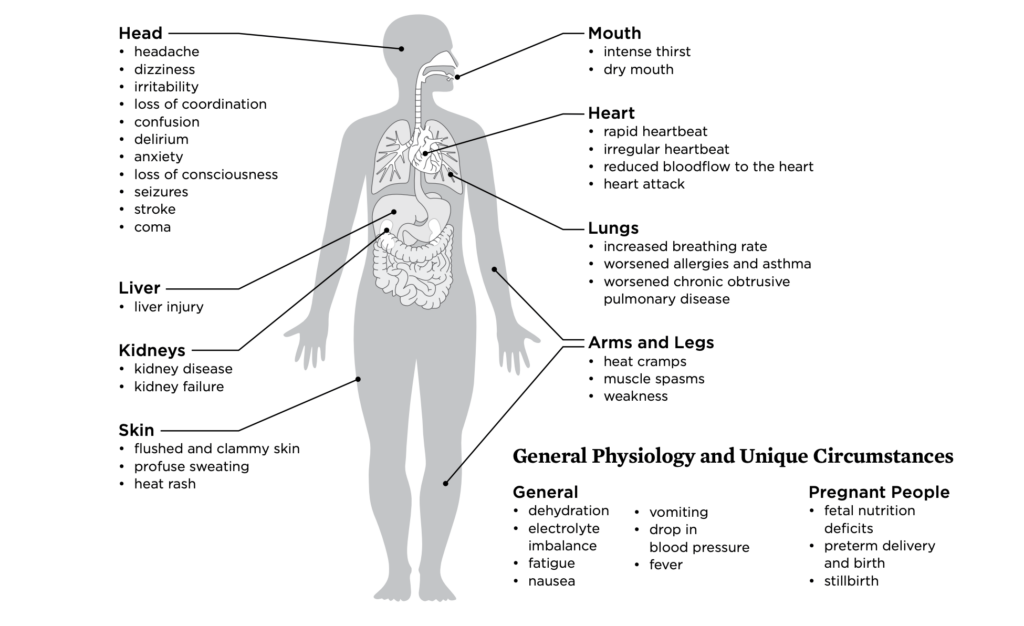

Exposure to extreme heat can take a toll on the human body. While “optimum” internal temperatures vary slightly from person to person, the core body temperature needs to stay within a narrow range of 36-37°C (97-99°F) to protect organs and for cells to function best. When the body becomes too hot, blood vessels in the skin dilate and heat is dissipated via the evaporation of sweat, which cools the surface of the skin, liberating heat transferred from the core.

High humidity can hinder this natural cooling process. In dry climates, sweat evaporation can continue to help cool the body even at relatively high temperatures, but that process becomes less effective as humidity increases. In very humid conditions, sweat doesn’t evaporate; instead, it just drips off the skin without cooling it. This is why dry heat can feel cooler than humid heat. The higher the combination of heat and humidity, the higher the risk of heat-related illness.

One of the most widely accepted ways to measure heat stress in humans is through a metric called the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT), a standard that was initially developed in the 1950s as part of a campaign to lower the risk of heat disorders during US military training. WBGT takes into account a variety of factors, including temperature, humidity, wind speed, sun angle, and cloud cover, to measure human heat stress in direct sunlight.32Brimicombe C, Lo CHB, Pappenberger F, Di Napoli C, Maciel P, Quintino T, Cornforth R, Cloke HL. Wet Bulb Globe Temperature: Indicating Extreme Heat Risk on a Global Grid. Geohealth. 2023 Feb 20;7(2):e2022GH000701. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9941479/

Under high WBGT, the risk of experiencing heat exhaustion increases. Heat exhaustion occurs when the body cannot get rid of excess heat and the internal body temperature rises. Signs of heat exhaustion include fatigue, nausea, headache, a fast heart rate, and shallow breathing. Those suffering from heat exhaustion must be given hydration and shade, or risk developing potentially fatal heatstroke.

Dehydration from heat can also have a serious impact on body organs, particularly the kidneys. When the body is dehydrated, the brain sends a signal to stop circulating as much blood to the kidneys to avoid losing fluid in the form of urine. The kidneys quickly become deprived of oxygen, which damages kidney cells and can cause acute kidney disease or, in extreme cases, kidney failure.33Chapman CL, Johnson BD, Parker MD, Hostler D, Pryor RR, Schlader Z. Kidney physiology and pathophysiology during heat stress and the modification by exercise, dehydration, heat acclimation and aging. Temperature (Austin). 2020 Oct 13;8(2):108-159. doi: 10.1080/23328940.2020.1826841. PMID: 33997113; PMCID: PMC8098077. The massive increase in chronic kidney disease affecting young and middle-aged construction and agricultural workers is believed to be the result of repeated kidney injury caused by dehydration and heat stress due to heavy workload.34Enbel, “Occupational Heat Stress in Outdoor Works: The Need for Regulation,” policy brief 4, Aug. 2023, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1W7CPiQ6tgXEbDBCHie4eDHgOTdayp8ul/view

In Central America, for example, chronic kidney disease of unknown cause (CKDu) has killed at least 20,000 young men over the last two decades, most of whom were sugarcane workers along the Pacific coast.35Dr. Marvin Gonzalez, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, “Why are thousands of sugarcane workers in northwestern Nicaragua dying from chronic kidney disease?,” news release, April 22, 2016, https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/newsevents/expert-opinion/why-are-thousands-sugarcane-workers-northwestern-nicaragua-dying-chronic#:~:text=Chronic%20kidney%20disease%20(CKD)%20has,kidney%20disease%20of%20unknown%20cause. A study of the Chichigalpa municipality of Nicaragua, where chronic kidney damage plagues the local population, found that increasing measures to prevent occupational heat stress, including shade breaks and improved hydration, appeared to reduce the risk of kidney injury among workers.36 Glaser J, Hansson E, Weiss I, et al. , “Preventing kidney injury among sugarcane workers: promising evidence from enhanced workplace interventions,” May 13, 2020, https://oem.bmj.com/content/oemed/early/2020/05/12/oemed-2020-106406.full.pdf.

Extreme heat can also exacerbate existing chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, cerebrovascular disease, kidney disease, and diabetes.37Abi, K, et al. “Hot weather and heat extremes: health risks,” The Lancet, August 2021, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)01208-3/fulltext People with cardiovascular issues are especially at risk because of the strain heat puts on the heart. For those with pre-existing conditions that affect circulation or the ability to sweat, such as diabetes, heat can become dangerous at much lower temperatures than it does for a healthy adult.

In addition to harming physical health, extreme heat can also impact mental health.38 Mullins JT, White C. Temperature and mental health: Evidence from the spectrum of mental health outcomes. J Health Econ. 2019 Dec;68:102240. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.102240. Epub 2019 Oct 4. PMID: 31590065. Heat not only fuels feelings like irritability and anger, but may also exacerbate mental illnesses, such as anxiety, schizophrenia, and depression.39Obradovich, N. “Empirical evidence of mental health risks posed by climate change,” PNAS, October 2018, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1801528115 Older adults, adolescents, and people with pre-existing mental illnesses are particularly vulnerable. Moreover, medications prescribed to treat or manage some mental health conditions, including widely-used lithium, can also impair the body’s ability to sweat and cool itself.40Martin-Latry, K. “Psychotropic drugs use and risk of heat-related hospitalisation,” European Psychiatry, September 2007, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0924933807013089?via%3Dihub

Image by Union of Concerned Scientists.41Dahl, Kristina, Erika Spanger-Siegfried, Rachel Licker, Astrid Caldas, John Abatzoglou, Nicholas Mailloux, Rachel Cleetus, Shana Udvardy, Juan Declet-Barreto, and Pamela Worth. 2019. Killer Heat in the United States: Climate Choices and the Future of Dangerously Hot Days. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists. https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/killer-heat-united-states-0

Exposure to extreme heat can also negatively impact and alter human behavior. Heat waves, for example, have been associated with an increase in intimate partner violence and online hate speech;42San-Barbero, B. “Heat wave and the risk of intimate partner violence,” Science of the Total Environment, December 2018, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969718324446 and researchers have found an association between high temperatures and hospitalizations for behavioral disorders.43Niu L, Girma B, Liu B, Schinasi LH, Clougherty JE, Sheffield P. Temperature and mental health-related emergency department and hospital encounters among children, adolescents and young adults. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2023 Apr 17;32:e22. doi: 10.1017/S2045796023000161. PMID: 37066768; PMCID: PMC10130844. Extreme heat can also discourage healthy behaviors, like exercising, which can result in cascading health impacts.44Romanello, M, et al. “The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels,” The Lancet, October 2022, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(22)01540-9/fulltext

The scale and nature of the resulting health impact depend not only on the mental and physical health of the individual, but also on the timing, intensity, and duration of a temperature event, the level of acclimatization of each individual,45Acclimatization means temporary adaptation of the body to work in the heat that occurs gradually when a person is exposed to it. and the adaptability of the local population, infrastructure and institutions to the prevailing climate.

Unfortunately, extreme heat can also interfere with some critical infrastructures, like health service delivery, which can further exacerbate the impact of the heat on human health. In 2021, for example, at least 11 people in Chennai, India, died from heat-related complications while waiting in line at hospital.46“What if a deadly heatwave hit India?” The Economist, July 2021, https://www.economist.com/what-if/2021/07/03/what-if-a-deadly-heat-wave-hit-india# During the July 2021 heat wave in British Columbia, Canada, several older people reportedly passed away while waiting for an ambulance.47“Canada: Disastrous Impact of Extreme Heat, Failure to Protect Older People, People with Disabilities in British Columbia,” Human Rights Watch, October 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/10/05/canada-disastrous-impact-extreme-heat Extreme heat can reduce access to medicine by impacting the storage and shelf life of medications (which often have recommended storage temperatures between 20-25°C, or 68-77°F), vaccines and other necessary supplies, including disinfectants, which can degrade at higher temperatures.48Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities (2008),” https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/disinfection/efficacy.html#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20the%20activity%20of,produce%20a%20potential%20health%20hazard.

Lastly, in addition to the more immediate health effects of extreme heat exposure, rising temperatures will also have longer-term health impacts, including by increasing the transmission of some vector-borne diseases.49Mojahed N, Mohammadkhani MA, Mohamadkhani A. Climate Crises and Developing Vector-Borne Diseases: A Narrative Review. Iran J Public Health. 2022 Dec;51(12):2664-2673. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v51i12.11457. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9874214/#:~:text=Rising%20temperatures%20favor%20agricultural%20pests,fever%20(2%2C%203).

The right to health is protected by Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which obligates states to take steps to promote, protect and fulfil “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.”50ICESCR, articles 11 and 12. As the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has made clear, the right to health “extends to the underlying determinants of health, such as food and nutrition, housing, access to safe and potable water and adequate sanitation, safe and healthy working conditions, and a healthy environment.”51UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, “General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health (Art. 12),” E/C.12/2000/4, Aug. 11, 2000, para. 4.

The right to health is also recognized in a range of other international human rights treaties. Under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, children have the right to enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. According to the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the state’s obligation to protect the health of children “also applies to the conditions that children need to lead a healthy life, such as a safe climate, safe and clean drinking water and sanitation, sustainable energy, adequate housing, access to nutritionally adequate and safe food, and healthy working conditions.”52UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, “General Comment No. 26: 2023) on children’s rights and the environment, with a special focus on climate change,” CRC/C/GC/26, Aug. 22, 2023, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/crccgc26-general-comment-no-26-2023-childrens-rights, para. 43.

The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights of 1981 similarly includes the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. Article 16(2) of the Charter adds that parties to the Charter “shall take the necessary measures to protect the health of their people and to ensure that they receive medical attention when they are sick.”53African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, art. 16(1), 16(2). The right to health is also protected by the Protocol of San Salvador of the American Convention on Human Rights (art. 10).

Inextricably linked to the right to health, in this context, is the right to a healthy environment. In July 2022, the UN General Assembly (UNGA) adopted a resolution declaring access to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment to be a universal human right.54UN General Assembly, A/RES/76/300, “The human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment,” July 28, 2022, https://undocs.org/Home/Mobile?FinalSymbol=A%2FRES%2F76%2F300&Language=E&DeviceType=Desktop&LangRequested=False. On March 23, 2023, the UN Human Rights Council adopted by consensus a resolution reaffirming the right to a healthy environment and calling on states to take steps to “respect, protect and fulfill” that right.55UN Human Rights Council, A/HRC/RES/52/23, “The human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment : resolution / adopted by the Human Rights Council on 4 April 2023,” https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/4010778?ln=en&v=pdf. The right to a healthy environment is also included in several regional human rights treaties, including the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the 1988 Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights, and in the Constitutions or domestic legislation of many individual countries.

Extreme heat and extreme heat events are already killing large numbers of people.56Qi Zhao, et. al. “Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with non-optimal ambient temperatures from 2000 to 2019: a three-stage modelling study,” Lancet, July 2021, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(21)00081-4/fulltext; IPCC WGII has found with “high confidence” that climate change will significantly increase heat-related morbidity and mortality. Tanya Lewis, “Why Extreme Heat is so Deadly,” Scientific American, July 22, 2021, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-extreme-heat-is-so-deadly/. According to one estimate, an estimated 480,000+ deaths per year were associated with “non-optimal” high temperatures between 2000 and 2019.57Qi Zhao, et. al. “Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with non-optimal ambient temperatures from 2000 to 2019: a three-stage modelling study,” Lancet, July 2021, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(21)00081-4/fulltext; The UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction cites a much lower number, noting that “more than” 166,000 people have died due to extreme temperatures between 1998 and 2017, but this number only accounts for deaths associated with disasters. If global mean temperature continues to rise to just under 2°C (3.6°F), annual heat-related deaths are projected to increase by 370 percent by mid-century, assuming no substantial progress on adaptation.58Romanello, M, et al. “The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: the imperative for a health-centred response in a world facing irreversible harms,” The Lancet, November 2023, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(23)01859-7/fulltext.

These heat-related deaths are occurring around the world. For example, government officials in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh reported 119 heat-related deaths in just a few days during a heat wave in June 2023.59Rajesh Kumar Singh, Piush Nagpal and Sibi Arasu, “Days of sweltering heat, power cuts in northern India overwhelm hospitals as death toll climbs,” AP, June 19, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/india-uttar-pradesh-bihar-heat-wave-deaths-273cbb7bd51a9e617e32240671b63c5a. And a recent study concluded that more 61,000 people died of heat-related causes in Europe during a heat wave in the summer of 2022.60Ballester, J., Quijal-Zamorano, M., Méndez Turrubiates, R.F. et al. Heat-related mortality in Europe during the summer of 2022. Nature Medicine (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02419-z The deaths were either direct consequences of the heat or caused by complications from underlying health conditions. That same year, heat-related deaths also hit a record in England, with at least 4,500 people dying of heat-related causes.61Carmen Aguilar Garcia, “Heat-related deaths in 2022 hit highest level on record in England,” Sept. 22, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/sep/22/heat-related-deaths-2022-hit-highest-level-record-england (accessed Sept. 26, 2023). In June 2021, hundreds of people in the Pacific Northwest died during a six day heat wave, with at least 486 deaths occurring in British Columbia,62Coletta, A. “Canada reports significant increase in heatwave deaths,” The Washington Post, June 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/06/29/canada-heat-dome-deaths/ 116 in Oregon,63Tabrizian, A. “Oregon’s heat wave death toll grows to 116,” The Oregonian, December 2021, https://www.oregonlive.com/data/2021/07/oregons-heat-wave-death-toll-grows-to-116.html and 78 in Washington.64Pailthorp, B. “Official death toll from heat wave at 78 in Washington – and it’s expected to rise,” National Public Radio, July 2021, https://www.knkx.org/environment/2021-07-08/official-death-toll-from-heat-wave-at-78-in-washington-and-its-expected-to-rise Studies have shown that the heat wave was at least 150 times more likely to have happened because of climate change.65Sjoukje YP, Sarah FK, Geert Jan van O, “Rapid attribution analysis of the extraordinary heatwave on the Pacific Coast of the US and Canada June 2021,” World Weather Attribution, 2021, https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/western-north-american-extreme-heat-virtually-impossible-without-human-caused-climate-change/.

Given the absence of a standard definition for what constitutes a heat-related death, it is likely that analyses of heat-related mortality are undercounts.66Donoghue, Edmund R. M.D.; Graham, Michael A. M.D.; Jentzen, Jeffrey M. M.D.; Lifschultz, Barry D. M.D.; Luke, James L. M.D.; Mirchandani, Haresh G. M.D. National Association of Medical Examiners Ad Hoc Committee on the Definition of Heat-Related Fatalities. Criteria for the Diagnosis of Heat-Related Deaths: National Association of Medical Examiners: Position Paper. The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology 18(1):p 11-14, March 1997. This is in part because heat-stress can exacerbate underlying conditions, which may then be listed as the cause of death with no reference made to heat.

As an example, according to official data, excessive heat caused the death of approximately 300 people in Australia in the last decade and caused the hospitalization of 7,000 people. However, a recent study found that there were over 36,000 deaths associated with heat between 2006 and 2017.67Australia National University, “We know that heat kills; accurately measuring these deaths will help us assess the impacts of climate change,” blog post, Feb. 25, 2021, https://iceds.anu.edu.au/research/research-stories/we-know-heat-kills-accurately-measuring-these-deaths-will-help-us-assess (accessed Jan. 12, 2024). Dr. Thomas Longden, the author of the study, noted that “this indicates that when doctors are filling out death certificates, they don’t focus on the external causes of death. Instead, they are mainly focused on the biological or internal causes of death.”68Ibid. Another analysis looking at deaths of farmworkers in California suggests that farmworker deaths from heat and/or air pollution far exceed the numbers recorded by California’s Occupational Health and Safety Association.69Linda Gross and Peter Aldhous, “Dying in the fields as temperatures soar,” Inside Climate News, Dec. 31, 2023, https://insideclimatenews.org/news/31122023/california-farmworkers-dying-in-the-heat/. As is the case in Australia, the biological or internal causes of death, such as heart attack, are listed on death certificate without consideration of the external factors that precipitate the internal causes, like heat.70Linda Gross and Peter Aldhous, “Dying in the fields as temperatures soar,” Inside Climate News, Dec. 31, 2023, https://insideclimatenews.org/news/31122023/california-farmworkers-dying-in-the-heat/.

Uncompensable heat — exposure to heat in a situation in which the body is unable to cool itself — causes the internal body temperature to rise. When the body’s internal temperature reaches 39.5°C (103°F) or higher, organs such as the brain, heart, gut, and kidneys can become damaged. A victim of heatstroke might experience abrupt changes in cognitive function and mental state, such as confusion, hallucination, and seizure. A person can fall unconscious and, in extreme cases, go into cardiac arrest. In acute instances, extreme heat can lead to sudden organ failure and death.71IPCC WGII, https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6/wg2/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf, at p. 1073.

All else held equal, exposure to six hours of uncompensable heat could result in a lethal rise in core temperatures for a healthy human being.72Carter M. Powis et al., “Observational and model evidence together support wide-spread exposure to noncompensable heat under continued global warming,” Science Advances, vol. 9, no. 36 (2023), DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adg9297. This threshold could be even lower for heat-sensitive groups, such as children or older people.

Chronic heat exposure can also trigger or exacerbate underlying diseases such as kidney disorders, hypertension, and chronic cardiovascular and respiratory diseases – leading to more premature deaths.

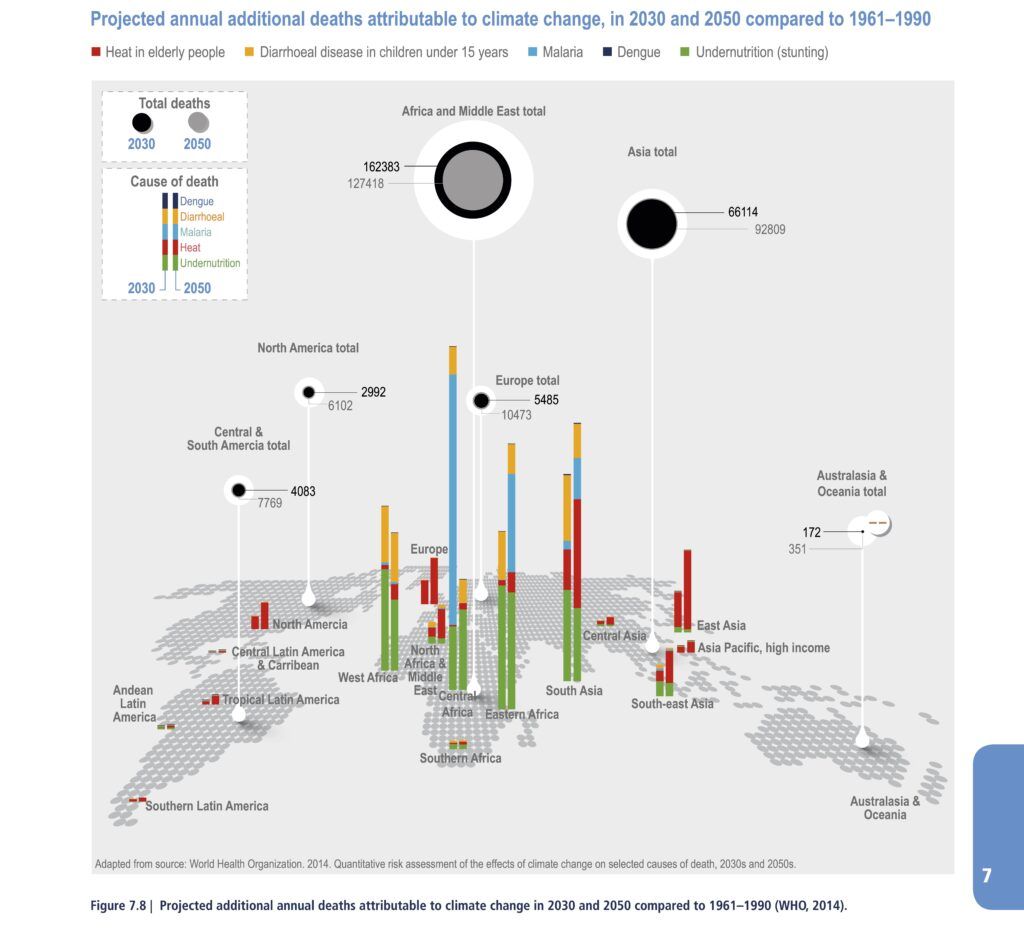

According to the IPCC, heat-related mortality, also linked to cardiovascular disease and other underlying conditions, will rise significantly by 2030, particularly under high emission scenarios.73IPCC Working Group II, “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6/wg2/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf. Asia, North Africa and the Middle East will be most seriously affected – but people in Europe and North America will also suffer.

The right to life is the most basic and a universal human right. Both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) specify that every person has the right to life. It is critical that governments, companies, and other actors take decisive steps to protect individuals from the very real and foreseeable risk that extreme heat and extreme heat events due to climate change will violate this most basic of rights.

IPCC graphic depicting projected annual additional deaths due to climate change, including deaths attributable to heat.74Figure 7.8 in Cissé, G., R. McLeman, H. Adams, P. Aldunce, K. Bowen, D. Campbell-Lendrum, S. Clayton, K.L. Ebi, J. Hess, C. Huang, Q. Liu, G. McGregor, J. Semenza, and M.C. Tirado, 2022: Health, Wellbeing, and the Changing Structure of Communities. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1041–1170, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.009.

Integral to the right to health and the right to life is the right to a safe and healthy work environment. Yet extreme heat is putting the health and lives of workers at risk, in part due to workplace conditions and policies that increase heat exposure and limit adaptive behaviors.75 See Chapter II, sections 3 and 4, on impact of heat and outdoor and indoor workers.

Working in high temperatures puts a huge strain on the human cardiovascular system, with extreme heat stress leading to illness and fatalities. Working in excessive heat can also increase the risk of workplace accidents and injuries.76Spector JT, Masuda YJ, Wolff NH, Calkins M, Seixas N. Heat Exposure and Occupational Injuries: Review of the Literature and Implications. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2019 Dec;6(4):286-296. doi: 10.1007/s40572-019-00250-8. PMID: 31520291; PMCID: PMC6923532. A recent study by the International Labor Organization found that working in excessive heat leads to nearly 19,000 deaths and 22.85 million occupational injuries every year.77International Labor Organization, “Ensuring Safety at Work in a Changing Climate,” report, 2024, https://www.ilo.org/publications/ensuring-safety-and-health-work-changing-climate.

Article 7(b) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Political Rights specifically recognizes “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of just and favourable conditions of work,” including, in particular, “safe and healthy working conditions.”78International Covenant on Economic, Social and Political Rights, art. 7(b). As the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has stated in interpreting the provision, the right to just and favourable conditions of work “applies to all workers in all settings, regardless of gender, as well as young and older workers, workers with disabilities, workers in the informal sector, migrant workers, workers from ethnic and other minorities, domestic workers, self-employed workers, agricultural workers, refugee workers and unpaid workers.”79UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, “General Comment No. 23 (2016) on the right to just and

favourable conditions of work (article 7 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights), E/C.12/GC/23, Apr. 27, 2016, https://www.refworld.org/legal/general/cescr/2016/en/122360, para. 5.

In order to protect this right, “states parties should adopt a national policy for the prevention of accidents and work-related health injury by minimizing hazards in the working environment.”80Ibid., para. 25. Access to safe drinking water, adequate sanitation facilities that also meet women’s specific hygiene needs, and materials and information to promote good hygiene are essential elements of a safe and healthy working environment.81Ibid, para. 31. So, too, is the protection against the health and safety risks posed by excess heat.

Article 11(1)(f) of the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women requires states to ensure that women have an equal right to protection of health and to safety in working conditions, including the safeguarding of the function of reproduction.82Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, art. 11(1()(f).

In June 2022, the International Labour Organization added a safe and healthy working environment to its Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.83 International Labour Organization, “Resolution on the inclusion of a safe and healthy working environment in the ILO’s framework of fundamental principles and rights at work,” ILC.110/Resolution 1, June 10, 2022, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_848632.pdf.

Extreme heat can disrupt education in a variety of ways, including via school closures when the schools are too hot for children to safely attend. In April 2024, temperatures in parts of Bangladesh soared to 42°C (108°F) and caused a nationwide shutdown of all schools, putting learning on pause for more than 32 million students.84Bangladesh: Extreme Heat Closes All Schools and Forces 33 Million Children Out of Classrooms, Save the Children, April 2024, https://www.savethechildren.net/news/bangladesh-extreme-heat-closes-all-schools-and-forces-33-million-children-out-classrooms Unfortunately, students in Bangladesh are no strangers to heat-related school closures. In June 2023, one year prior, Bangladesh similarly closed thousands of primary schools during a prolonged heat wave in which temperatures in Dhaka reached 40°C (104°F).85“Bangladesh shuts schools, cuts power in longest heatwave in decades,” France24, June 7, 2023, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20230607-bangladesh-shuts-schools-cuts-power-in-longest-heatwave-in-decades. As Umair, an 8-year-old student in Dhaka told Climate Rights International, “My school was closed off for four days from the heat wave in Dhaka this summer. Classes just stopped.”86Climate Rights International interview with Umair, Dhaka, Bangladesh, July 8, 2023.

Bangladesh is only one of the many places in which heat has caused school closures. In April 2023, several states in India were forced to close schools when temperatures exceeded 44°C (111°F) in some areas.87Rebecca Ratcliffe, “Severe heatwave engulfs Asia causing deaths and forcing schools to close,” Guardian, April 19, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/weather/2023/apr/19/severe-heatwave-asia-deaths-schools-close-india-china. In September 2022, nearly 150 schools in four U.S. cities were closed due to heat.88Nick Visser, “Schools From Philadelphia To Los Angeles Close Early Due To Heat Waves,” Huffington Post,, August 31, 2022, https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/heat-waves-schools-closing_n_630efcd6e4b0da54bae3f6d3. On March 18, 2024, South Sudan announced the closure of all of its schools in preparation for a heat wave expected to last up to two weeks, during which temperatures were expected to reach 45°C (113°F).89Associated Press, “South Sudan closes schools in preparation for 45C heatwave,” Guardian, Mar. 18, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/mar/18/south-sudan-closes-schools-in-preparation-for-45c-heatwave?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other. In April 2024, the Philippines closed all public schools due to soaring temperatures.90Jason Gutierrez, “Philippines Closes Schools as Heat Soars to ‘Danger’ Level,” New York Times, April 29, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/29/world/asia/philippines-heat-schools-jeepney.html.

Primary school in Bangladesh. Photo by SyedAminul, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Schools in some places can continue to teach through online learning during school closures, but that option is not available for many. As the shift to online learning during the Covid-19 pandemic made clear, schools in poorer areas lack the resources to do so. Children from marginalized communities are less likely to have internet access or access to an internet-connected device even if online teaching is available.91UNESCO, “An Ed-Tech Tragedy: Educational technologies and school closures in the time of COVID-19,” report, https://www.unesco.org/en/digital-education/ed-tech-tragedy. Students from the poorest families are thus more likely to be denied education in a heat wave — widening already deep educational inequalities.

Heat can affect learning even when schools remain open. Climate-exacerbated temperature extremes can interfere with cognitive development92Goodman, et al. “Heat and Learning” (NBER Working Paper Series), National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2018, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/joshuagoodman/files/w24639.pdf and have been linked to both reduced test scores and overall rates of learning.93Park, R.J., Behrer, A.P. & Goodman, J. Learning is inhibited by heat exposure, both internationally and within the United States. Nat Hum Behav 5, 19–27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-00959-9 A study by the US Environmental Protection Agency found that temperature increases of 2°C (3.6°F) and 4°C (7.2°F) of global warming are associated with, on average, 4% and 7% reductions in academic achievement per child, respectively, relative to average learning gains experienced each school year.94US Environmental Protection Agency, “Climate Change and Children’s Health and Well-Being in the United States,” report, https://www.epa.gov/cira/climate-change-and-childrens-health-and-well-being-united-states-report. Another study that evaluated data from 144 million students across 58 countries found a negative association between the number of hot school days and the rate of learning.95Park, R.J., Behrer, A.P. & Goodman, J. Learning is inhibited by heat exposure, both internationally and within the United States. Nat Hum Behav 5, 19–27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-00959-9

As a nine-year-old student from Karachi described it to Climate Rights International:

I feel like I am not able to study properly or concentrate because the classroom is so hot, and all of the kids are so tired because of the heat. We are not able to learn or pay attention to what the teacher is saying because of that.96CRI interview with Hania Saud, Karachi, September 2023.

The impact of heat on education falls most heavily on students and communities that lack the resources to adapt.

Education is both a human right in itself and an indispensable means of realizing other human rights. Under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), every person has the right to an education, and governments have a duty to ensure that this right is respected, protected, and fulfilled. Under the ICESCR, educational institutions must be available in sufficient quantity in the jurisdiction and accessible to everyone without discrimination. Accessibility includes both physical accessibility and economic accessibility.97 UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, “General Comment No. 13: The Right to Education (article 13),” E/C.12/1999/10, Dec. 8, 1999, para. 6, https://www.ohchr.org/en/resources/educators/human-rights-education-training/d-general-comment-no-13-right-education-article-13-1999#:~:text=The%20right%20to%20education%2C%20like,and%20an%20obligation%20to%20provide.

According to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the specifics each institution requires to function depends upon numerous factors, including the developmental context within which they operate, but “all institutions and programmes are likely to require buildings or other protection from the elements, sanitation facilities for both sexes, safe drinking water, trained teachers receiving domestically competitive salaries, teaching materials, and so on.”98 Ibid.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child has stressed that states should build “safe, healthy and resilient infrastructure for effective learning.”99UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, “General Comment No. 26: 2023) on children’s rights and the environment, with a special focus on climate change,” CRC/C/GC/26, Aug. 22, 2023, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/crccgc26-general-comment-no-26-2023-childrens-rights, para. 55. This includes “classrooms with adequate heating and cooling and access to sufficient, safe and acceptable drinking water and sanitation facilities.”100UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, “General Comment No. 26: 2023) on children’s rights and the environment, with a special focus on climate change,” CRC/C/GC/26, Aug. 22, 2023, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/crccgc26-general-comment-no-26-2023-childrens-rights, para. 55.

The importance of the right to education is reflected in that fact that it has been affirmed in a wide range of additional human rights treaties, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child,101Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted Nov. 20, 1989, entered into force Sept. 2, 1990, art. 28, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women,102Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, adopted Dec. 18, 1979, entered into force Sept. 3, 1981, art. 10, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/cedaw.pdf. the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities,103Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities, adopted Dec. 12, 2006, entered into force May 3, 2008, art, 24, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities. and the Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families.104Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, adopted Dec. 18, 1990. Entered into force July 1, 2003, art. 30, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-convention-protection-rights-all-migrant-workers. The right to education is also protected under regional human rights treaties, including the European Convention on Human Rights,105European Convention on Human Rights, Protocol 1, adopted March 20, 1952, entered into force Nov. 1, 1998, article 2, https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr/Library_Collection_P1postP11_ETS009E_ENG#:~:text=Article%201%20%C5%93%20Protection%20of,general%20principles%20of%20international%20law. the American Convention on Human Rights,106Organization of American States, American Convention on Human Rights art. 26, Nov. 22, 1969, O.A.S.T.S. No. 36, 1144 U.N.T.S. 123 [hereinafter American Convention]; Organization of American States, Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (“Protocol of San Salvador”) art. 13, opened for signature N signature Nov. 17, 1988, O.A.S.T.S. No. 69 (entered into force Nov. 16, 1999). and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.107African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, adopted June 1981, entered into force Oct. 21, 1986, art. 17(1), https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/36390-treaty-0011_-_african_charter_on_human_and_peoples_rights_e.pdf.

Climate change is already affecting water access for people around the world, causing more severe droughts and floods. Increasing global temperatures are one of the main contributors to this problem. Working Group I of the IPCC found with high confidence that warming over land drives an increase in atmospheric evaporative demand and in the severity of drought events.108IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, “Working Group I: The Physical Science Basis,” TS2.6, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/chapter/technical-summary/#undefined. Droughts put access to water at risk.

In the period 2012–21, on average, almost 47 percent of global land area was affected by at least one month of extreme drought each year, an increase of 29 percent from the period 1951–60.109“The 2022 Report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels,” Oct. 25, 2022, https://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140-6736(22)01540-9/fulltext. The Middle East and north Africa, where 41 million people lack access to safe water and 66 million do not have basic sanitation services, were particularly affected, with some areas experiencing more than 10 extra months of extreme drought.110 Ibid.

The Global Drought Monitor Consortium found that the record heat experienced in 2023 “affected the water cycle in various ways,” including by exacerbating drought conditions.111Global Water Monitor, “2023 Summary Report,” Jan. 7, 2024, https://globalwater.online/globalwater/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/GlobalWaterMonitor_2023_SummaryReport.pdf. Looking forward, the report said, “the greatest risk of developing or intensifying drought” over the next year is in much of Central and South America, southern Africa, and western Australia.

Water quality is also affected by climate change, as higher water temperatures and more frequent floods and droughts are projected to exacerbate many forms of water pollution – from sediments to pathogens and pesticides.112Bates, B.C., Z.W. Kundzewicz, S. Wu and J.P. Palutikof, Eds., 2008: Climate Change and Water. Technical Paper of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC Secretariat, Geneva, 210 pp.

The human right to water, under international law, entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, physically accessible, and affordable water for personal and domestic use.113UN CESCR, General Comment No. 15, para. 2, https://www.refworld.org/docid/4538838d11.html (accessed October 3, 2023); UN General Assembly, The human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation, Resolution 70/169, U.N. Doc. A/RES/70/169, December 17, 2015, para 2, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/442/72/PDF/N1544272.pdf?OpenElement Personal and domestic uses “ordinarily include drinking, personal sanitation, washing of clothes, food preparation, personal and household hygiene.”114UN CESCR, General Comment No. 15, para 12(a). The costs and charges associated with securing water must not compromise or threaten the realization of other human rights.115Ibid., para. 12(c)(2).

While the adequacy of water supply varies according to conditions, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Water and Sanitation has stated that to “ensure the full realization of the right, States should aim for at least 50 to 100 liters per person per day.”116UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation, “Frequently Asked Questions,” https://sr-watersanitation.ohchr.org/en/rightstowater_5.html (accessed July 12, 2023).

A 2020 report by the World Health Organization (WHO) defined “optimal access” to water—which carries “low” levels of health concern—as having more than 100 liters per person per day, supplied to the home through multiple taps and continuously available. It defined “intermediate access”—with a “medium” level of health concern—as an average quantity of about 50 liters per person per day, supplied through one tap on the plot of land, or within 100 meters or 5 minutes total of collection time. It defined “basic access”—carrying “high” levels of health concern—as an average quantity unlikely to exceed 20 liters per person per day, with 100-1000 meters in distance or 5 to 30 minutes in collection time.117Guy Howard et al., “Domestic water quantity, service level and health,” World Health Organization, 2020 (second edition), https://www.globalwaters.org/resources/assets/domestic-water-quantity-service-level-and-health p. x

In addition to water for personal and domestic use, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has said that States should ensure that “there is adequate access to water for subsistence farming and for securing the livelihoods of indigenous peoples.”118UN CESCR, General Comment No. 15, para 7; Inter-American Court of Human Rights, Lhaka v. Argentina, Judgment of February 6, 2020, para. 228 (quoting UN CESCR, General Comment No. 15).

Climate change is already a leading cause of hunger, second only to conflict, according to the World Food Program.119“How Climate Drives Hunger: Food Security Climate Analyses, Methodologies & Lessons 2010-2016,” World Food Programme, October 2017, https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000023293/download/?_ga=2.80832415.960214306.1666184894-1780604223.1666184894&_gac=1.247129520.1666184894.EAIaIQobChMIscLssq7s-gIVAurtCh1HNQNqEAAYASAAEgIxF_D_BwE Foreseeable climate change driven phenomena, including changes in precipitation patterns, desertification or salinization of land, droughts and floods, loss of arable land due to rising sea levels, and extreme weather events, will combine to greatly exacerbate existing threats to food security, particularly in regions of Asia, Africa, South America, and island states. In the absence of timely mitigation and adaptation measures, these regions may face starvation and/or severe hunger with tragic regularity.

Extreme heat damages agricultural yields and decreases food supply and shelf life, contributing to both long- and short-term food insecurity.120Carolin Kroeger, Aaron Reeves, Extreme heat leads to short- and long-term food insecurity with serious consequences for health, European Journal of Public Health, Volume 32, Issue 4, August 2022, Page 521, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckac080 Extreme heat can also lead to dehydration and heat stress in the livestock upon which many depend. For example, the heat wave that hit Niger in 2023, with temperatures reaching 47°C (116.6°F), reportedly led to increased mortality among livestock.121“Niger in the grip of a blistering heatwave with high temperatures,” AfricaNews, Sept. 7, 2023, https://www.africanews.com/2023/07/09/niger-in-the-grip-of-a-blistering-heatwave-with-high-temperatures/.

New data indicates that a higher frequency of heat waves and droughts was associated with 127 million more people experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity in 2021 than annually between 1981 and 2010, putting millions of people at risk of malnutrition and potentially irreversible health effects.122Romanello, M, et al. “The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: the imperative for a health-centred response in a world facing irreversible harms,” The Lancet, November 2023, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(22)01540-9/fulltext

The increasing intensity and frequency of extreme weather events, including heat waves, can damage crops and agricultural lands, affect livestock, disrupt supply chains, and affect food availability and stability of supplies. Increasing water temperatures and ocean acidification threaten fish stocks, thereby undermining marine food supplies.

If global mean temperature continues to rise to just under 2°C (3.6°F), heat waves alone could lead to 524.9 million additional people experiencing moderate-to-severe food insecurity by 2041–60 compared with the 1995–2014 baseline.123Romanello, M, et al. “The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: the imperative for a health-centred response in a world facing irreversible harms,” The Lancet, November 2023, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(23)01859-7/fulltext, indicator 1.4.

Under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), everyone has the right to adequate food. The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has stated that the core content of the right to adequate food implies, “The availability of food in a quantity and quality sufficient to satisfy the dietary needs of individuals, free from adverse substances, and acceptable within a given culture; … The accessibility of such food in ways that are sustainable and that do not interfere with the enjoyment of other human rights.”124UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, “General Comment No. 12: The Right to Adequate Food,” E/C.12/1999/5, May 12, 1999, https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g99/420/12/pdf/g9942012.pdf?token=cw4Krq8Ll7hK8OUSyz&fe=true, para. 9.

Every state is obliged to ensure for everyone under its jurisdiction access to the minimum essential food which is sufficient, nutritionally adequate and safe, to ensure their freedom from hunger.125Ibid, para. 14.

A fast-developing area of international law and norms concerns the rights of future generations. Decisions being taken by those currently living can affect the lives and rights of those born years, decades, or many centuries in the future. Climate change has created greater urgency about the need to recognize the intergenerational dimensions of present conduct.

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has stressed that, while the rights of children who are present on Earth require immediate urgent attention, the children constantly arriving are also entitled to the realization of their human rights to the maximum extent.126UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, “General Comment No. 26: 2023) on children’s rights and the environment, with a special focus on climate change,” CRC/C/GC/26, Aug. 22, 2023, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/crccgc26-general-comment-no-26-2023-childrens-rights, para. 11. Beyond their immediate obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, States bear the responsibility for foreseeable environment-related threats arising as a result of their acts or omissions now, the full implications of which may not manifest for years or even decades.127Ibid.

Failure to act on climate change poses existential risks to future generations. By 2100, temperatures could rise to the point that just going outside for a few hours in some parts of the Middle East, Africa, and Asia will exceed the “upper limit for survivability, even with idealized conditions of perfect health, total inactivity, full shade, absence of clothing, and unlimited drinking water,” according to a 2020 study in Science Advances.128Aryn Baker & Ted Kashi, “Thousands of Migrant Workers Died in Qatar’s Extreme Heat. The World Cup Forced a Reckoning,” Time, Nov. 3, 2022, https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/thousands-migrant-workers-died-qatars-extreme-heat-world-cup-forced-reckoning,

The Maastricht Principles on the Human Rights of Future Generations, adopted in 2023 and endorsed by nearly sixty leading legal and human rights experts from around the world, seek to clarify the state of international human rights law as it applies to future generations.129Maastricht Principles on the Human Rights of Future Generations, adopted Feb. 3, 2023, https://www.rightsoffuturegenerations.org/the-principles. According to those principles, states have obligations to respect, protect, and fulfil the human rights of future generations, who have the right to equal enjoyment of all human rights. States and other duty bearers must refrain from any conduct which can reasonably be expected to result in, or perpetuate, any form of discrimination against future generations.130Maastricht Principles,,art. 6(a).

Where there are reasonable grounds for concern that the impacts of State or non-State conduct, whether singly or in aggregate, may result in violations of the human rights of future generations, the Maastricht Principles take the position that States have an obligation to prevent the harm, and must take all reasonable steps to avoid or minimize such harm. Doing so demands a strong approach to precaution, particularly when conduct threatens irreparable harm to the Earth’s ability to sustain human life or to the common biological and cultural heritage of humankind.131Maastricht Principles, art. 9.

Failure of states to rein in emissions will leave future generations with a world that is largely unlivable, in clear violation of their rights to life and each of the rights discussed above, among many others.

While extreme heat and extreme heat events pose risks to everyone, some groups are more at risk than others. Women, children, people living in poverty, older people, pregnant people, and people with disabilities may suffer disproportionately from the impacts of extreme heat. Those in confined spaces without adequate cooling, including prisons and factories, and those who work outdoors, are also at increased risk.

Children are more vulnerable to heat-related illness and death than adults.132“Protecting Children’s Health During and After Natural Disasters: Extreme Heat,” United States Environmental Protection Agency, https://www.epa.gov/children/protecting-childrens-health-during-and-after-natural-disasters-extreme-heat This is because they are less able to regulate their body temperature and are dependent on others to regulate the temperature of their environment.133Huettman, E. Heat Waves Affect Children More Severely. Scientific American. August 2022. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/heat-waves-affect-children-more-severely/ Children are particularly vulnerable to dehydration and heat stress as a result of their body surface to volume ratio.134Kakkad K, Barzaga ML, Wallenstein S, Azhar GS, Sheffield PE. Neonates in Ahmedabad, India, during the 2010 heat wave: a climate change adaptation study. J Environ Public Health. 2014;2014:946875. doi: 10.1155/2014/946875. Epub 2014 Mar 10. PMID: 24734050; PMCID: PMC3964840. They are more likely to develop respiratory disease, kidney disease, and fever during hot weather.135Xu Z, Sheffield PE, Su H, Wang X, Bi Y, Tong S. The impact of heat waves on children’s health: a systematic review. Int J Biometeorol. 2014 Mar;58(2):239-47. doi: 10.1007/s00484-013-0655-x. Epub 2013 Mar 23. PMID: 23525899.

A doctor in Bangladesh told Climate Rights International that during a June 2023 heat wave she treated numerous children under the age of five suffering from dehydration, with nausea, decreased urination, dizziness, and discomfort.136CRI interview with a doctor in Baliakandi, Bangladesh, June 20, 2023 (asked not to be identified).

Children can also experience respiratory impacts as a result of rising temperatures. Extreme heat can exacerbate the health impacts of poor air quality, and because children have less developed respiratory systems and relatively high rates of respiration, they are more vulnerable to the impacts of air pollution than adults.137Anna Makri and Nikolaos Stilianakis, “Vulnerability to air pollution health effects,” International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, vol. 211, 326-336 (2008), DOI: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2007.06.005, avail. at https://learning-cleanairasia.org/lms/library/ga3/45-Vulnerability-to-air-pollution-health-effects.pdf.

Childhood exposure to heat waves is increasing. Children younger than one year of age experienced 4.4 more heat wave days per child per year between 2012 and 2021 than between 1986 and 2005.138Romanello, M, et al. “The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels,” The Lancet, October 2022, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(22)01540-9/fulltext UNICEF estimates that 559 million children around the world are already being exposed to high heat wave frequency, meaning they live in areas that experience an average of 4.5 or more heatwaves annually, and that by 2050 over 2 billion children (“virtually every child on Earth”) will face more frequent heat waves.139United Nations Children’s Fund, The Coldest Year of the Rest of their Lives: Protecting children from the escalating impacts of heatwaves, UNICEF, New York, October 2022.

As the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child stated in its General Comment 26:

States should take positive measures to ensure that children are protected from foreseeable premature or unnatural death and threats to their lives that may be caused by acts and omissions, as well as the activities of business actors, and enjoy their right to life with dignity. Such measures include the adoption and effective implementation of environmental standards, for example, those related to air and water quality, food safety, lead exposure and greenhouse gas emissions, and all other adequate and necessary environmental measures that are protective of children’s right to life.

Heat-vulnerability is influenced by advanced age more than any other non-modifiable risk factor.140Robert Meade, Ashley Ackerman, et al., “Physiological factors characterizing heat-vulnerable older adults: A narrative review,” Environment International, vol. 144, Nov. 2020, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016041202031864X#b0390.

Aprdous Hossain, a 74-year-old widow living in Dhaka, described the impact of the intense heat in the summer of 2023 to Climate Rights International:

This summer I feel very tired. My energy is draining with my sweat. When I was in the kitchen you see I could not come out and sit here to take my lunch. I was so exhausted. I eat only small portions of rice because I am too hot. I am always feeling dizzy, dizzy, dizzy. I am not sleeping, but I feel there is a dizziness because it is so hot.141Climate Rights International interview with Aprdous Hossain, Dhaka, Bangladesh, June 10, 2023.

Older people are overrepresented in heat wave-related excess mortality statistics across the globe.142Margareta Windisch, “Denaturalising heatwaves: gendered social vulnerability in urban heatwaves, a review,” https://www.bnhcrc.com.au/sites/default/files/managed/downloads/margareta_windisch.pdf. More than half of the heat-related deaths in Europe during the summer of 2022 were people aged 80 and older.143Ballester, J., Quijal-Zamorano, M., Méndez Turrubiates, R.F. et al. Heat-related mortality in Europe during the summer of 2022. Nature Medicine (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02419-z In a study of Mexico City, Mexico, São Paulo, Brazil, and Santiago, Chile, researchers found that susceptibility to heat-related mortality increased with age in all cities.144Bell ML, O’Neill MS, Ranjit N, Borja-Aburto VH, Cifuentes LA, Gouveia NC. Vulnerability to heat-related mortality in Latin America: a case-crossover study in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Santiago, Chile and Mexico City, Mexico. Int J Epidemiol. 2008 Aug;37(4):796-804. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn094. Epub 2008 May 29. PMID: 18511489; PMCID: PMC2734062. In Japan, approximately 80% of heatstroke deaths over recent years have been among people over 65.145Fujimoto M, Hayashi K, Nishiura H. Possible adaptation measures for climate change in preventing heatstroke among older adults in Japan. Front Public Health. 2023 Sep 22;11:1184963. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1184963. PMID: 37808973; PMCID: PMC10556232.