Photo by NCEA Online.

In 2006, commercially viable oil deposits were discovered under and around Lake Albert in Western Uganda.1https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2014/02/25/local-communities-and-oil-discoveries-a-study-in-ugandas-albertine-graben-region/ The region quickly became one of the world’s top oil exploration hotspots and, between 2010 and 2015, successful appraisals boosted Uganda’s proven crude oil reserves from zero to almost 2.5 billion barrels.2https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/UGA

As of the time of writing, however, oil production in Uganda has yet to begin.3https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/1/24/uganda-to-unveil-first-commercial-oil-production-drilling-programme Uganda is landlocked and the remote location of its reserves – more than 700 miles (1,126 km) inland from the nearest major port in Mombasa, Kenya – has proven to be a significant barrier to the commercialization of its oil, requiring the construction of a trans-national pipeline to transport the oil to international markets.4https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621045/rr-empty-promises-down-line-101020-en.pdf

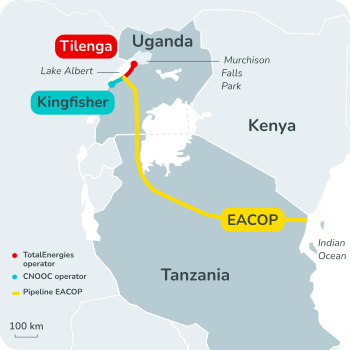

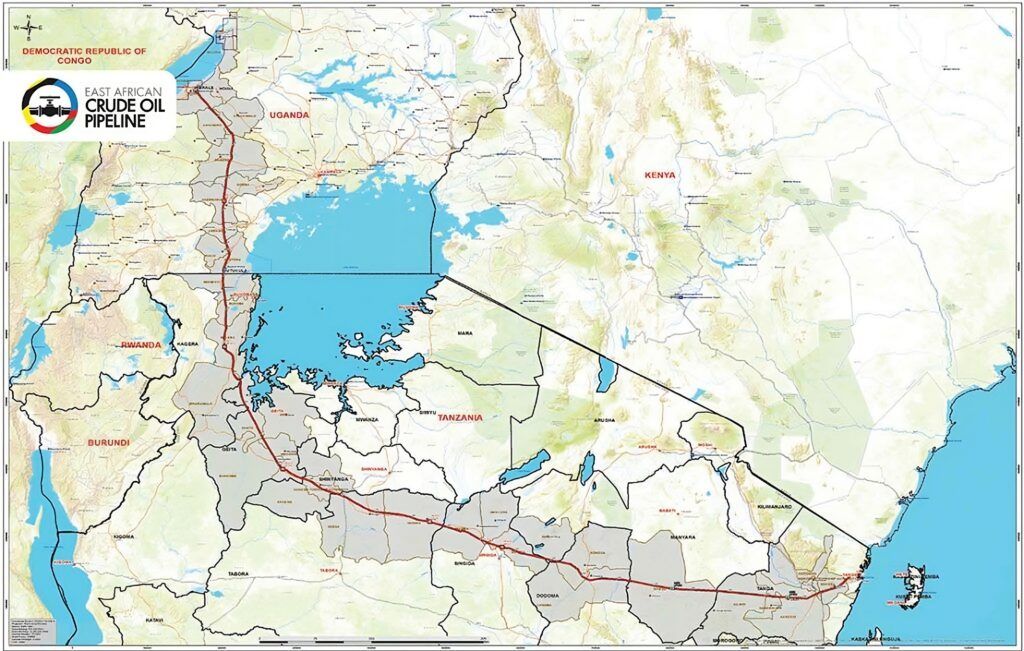

In 2017, after long negotiations, and the abandonment of a proposed Uganda-Kenya pipeline, the governments of Uganda and Tanzania agreed to develop the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP).5https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/uganda-tanzania-begin-construction-of-key-oil-pipeline/877028 The project is intended to carry crude oil almost 900 miles from oil fields on the shores of Uganda’s Lake Albert, through the basin of Lake Victoria, to the Port of Tanga on the Tanzanian coast. If completed, it would be the longest heated oil pipeline in the world (heating is necessary because of the viscous and waxy nature of the Albertine oil).6https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2022/02/05/a-big-ugandan-oil-project-is-progressing-at-last https://jpt.spe.org/tanzania-greenlights-worlds-longest-heated-crude-pipeline

Projected to cost roughly $5 billion, the pipeline will be primarily operated and financed by Paris-based TotalEnergies and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), with significant investments by the Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC) and the Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC).7https://www.gem.wiki/East_African_Crude_Oil_Pipeline_(EACOP) https://www.ogj.com/pipelines-transportation/pipelines/article/14288579/uganda-approves-eacop-construction-to-start-late-2023 In addition to the pipeline, the consortium is also financing two upstream oil projects: the Tilenga project, operated by TotalEnergies, and the smaller Kingfisher project, operated by CNOOC.8https://www.upstreamonline.com/field-development/tilenga-kingfisher-huge-contracts-near-as-uganda-and-tanzania-agree-key-oil-deals/2-1-993890

The pipeline’s backers have promised that it will bring significant investment and benefits to both Uganda and Tanzania, including the development of new infrastructure, logistics, and technology transfer, as well as improvement to the livelihoods of communities along the route.9https://eacop.com/ Despite these purported benefits, however, the project has been subject to significant delays, partially due to the Covid-19 pandemic and regulatory disputes, but also as a result of strong opposition from local communities in Uganda and Tanzania and pressure from domestic and international climate and human rights activists and organizations.10https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/1/24/uganda-to-unveil-first-commercial-oil-production-drilling-programme Opponents argue that the pipeline and its associated infrastructure project – which would be one of the largest in East African history – would entail numerous environmental and social risks, including: physical and economic displacement; a mismanaged and delayed compensation process; threats to livelihoods from oil spills; the loss or destruction of sites of spiritual value; and significant disturbance to one of the most ecologically diverse and wildlife-rich regions of the world.11https://www.banktrack.org/download/crude_risk/cruderisk_eacop_briefing_nov2020_1.pdf

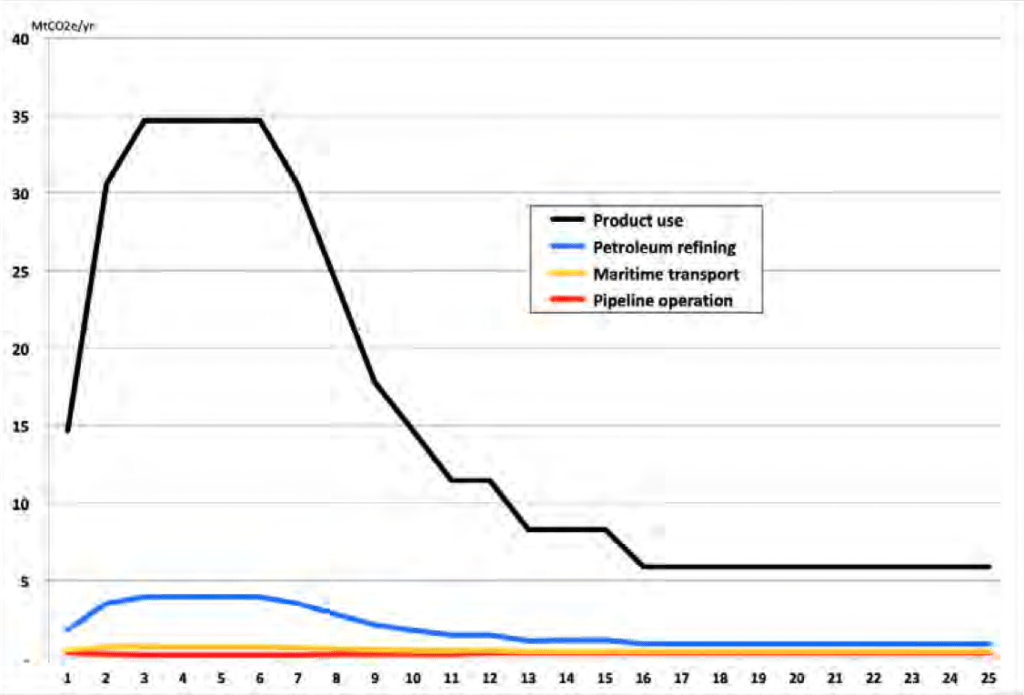

Domestic and international NGOs have also condemned the pipeline as facilitating the generation of massive amounts of climate-warming carbon dioxide and therefore incompatible with the Paris agreement’s 1.5C° warming target and a livable planet.12https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/oct/27/east-african-crude-oil-pipeline-carbon https://news.mongabay.com/2021/04/totals-east-african-oil-pipeline-to-go-ahead-despite-stiff-opposition/ Indeed, according to an analysis by the Climate Accountability Institute (CAI), the EACOP project would produce around 379 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions over 25 years, with peak annual emissions more than doubling the current annual emissions of Uganda and Tanzania combined.13https://climateaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/CAI-EACOP-Rptlores-Oct22.pdf

In late 2022, sixteen years after the Albertine oil was discovered, TotalEnergies and CNOOC announced that they had reached a Final Investment Decision (FID) on EACOP and its associated projects.14https://www.ogj.com/pipelines-transportation/pipelines/article/14288579/uganda-approves-eacop-construction-to-start-late-2023 Nevertheless, owing to continued local and international opposition to the pipeline, numerous banks and insurance companies have publicly stated that they will not participate financially in the project. Thus, as of the time of writing, the project’s backers have been unable to secure the financing, insurance, and other agreements necessary to begin oil production.15https://www.stopeacop.net/our-news/there-is-still-a-long-way-to-go-before-eacop-reaches-financial-close-activists-opposed-to-pipeline-say

If the project goes forward, human rights abuses are likely to be severe and escalate, while EACOP will likely be a carbon bomb that exacerbates climate change. For the reasons explained below, #StopEACOP, a coalition of over 260 civil society organizations, more than 100 of which are based in Africa, has called for an end to the project.16https://www.stopeacop.net/our-coalition

The historical record of oil in Uganda begins with small oil seepages on the shores of Lake Albert, which were well known to generations of Indigenous people who lived in the area.17https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/WPM-601.pdf Evaluation and documentation of this oil occurred as early as 1925 and continued into the 1930s, but stalled during World War II. Exploration remained limited until the 1980s, in large part due to the country’s post-independence period of political instability and civil war, as well as the operational challenges and costs of exploration in such a remote area.18https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/special-topics/Emerging_East_Africa_Energy

Throughout the remainder of the twentieth century, oil exploration in Uganda became increasingly consistent and modern, with the establishment of new legislative and regulatory frameworks, the undertaking of geological and geophysical surveys, and the licensing of foreign and domestic companies for drilling.19https://www.petroleum.go.ug/index.php/who-we-are/who-weare/petroleum-exploration-history Nevertheless, despite these and similar efforts in neighboring countries, Sub-Saharan Africa – and East Africa, in particular – remained one of the most oil-impoverished regions in the world well into the twenty-first century, holding just 4% of the world’s proven oil reserves as late as 2007.20https://www.imf.org/-/media/Websites/IMF/imported-flagship-issues/external/pubs/ft/reo/2007/AFR/ENG/_sreo0407pdf.ashx

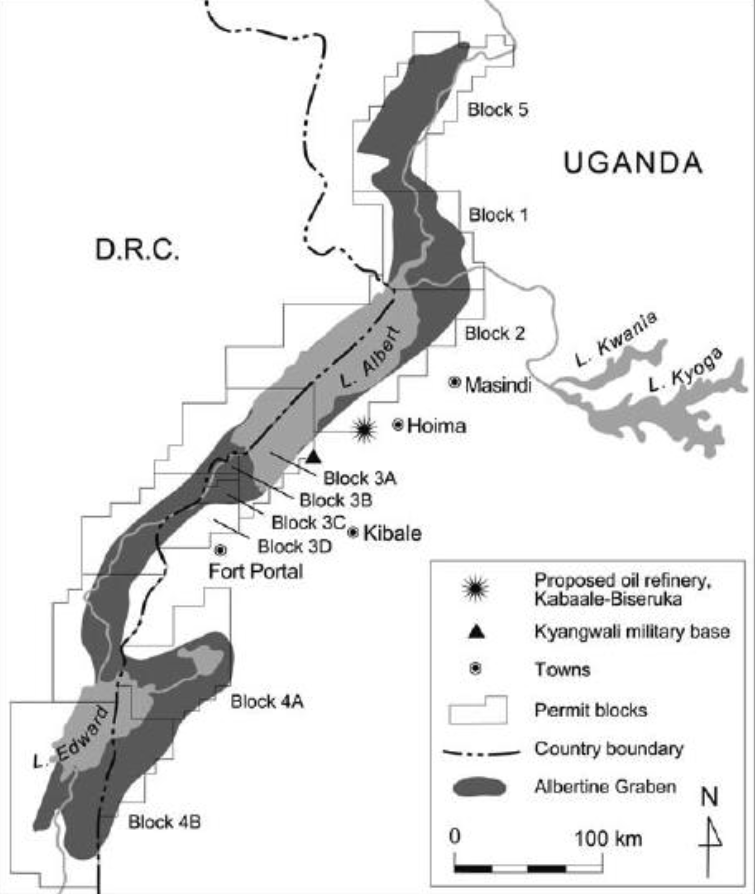

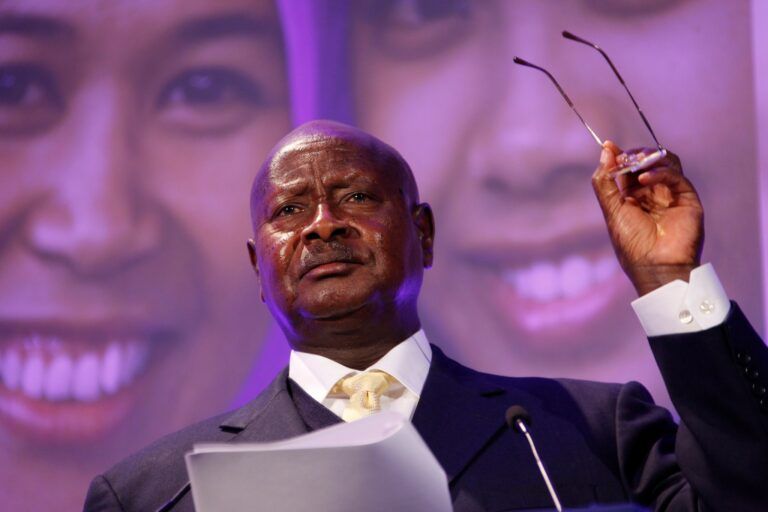

This changed in October 2006 when an Australia-based “wildcatter” petroleum company, Hardman Resources, made the first commercial oil discovery in Ugandan history, on the eastern shores of Lake Albert, between the small settlements of Kauiso and Tonya.21https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/business/technology/journey-to-fid-history-of-petroleum-exploration-3711366 Drilling deep into the Albertine Graben, a Mesozoic-Cenozoic rift basin into which thick sediments have accumulated over hundreds of millions of years, Hardman reported “good oil shows.”22https://www.ogj.com/exploration-development/article/17280550/hardman-reports-oil-shows-in-ugandan-well To announce and celebrate the discovery, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni convened a national prayer festival, during which he thanked God “for having created for us a rift valley twenty-five million years ago,” and for providing “the wisdom and foresight to develop the capacity to discover this oil.”23https://www.theguardian.com/katine/2009/dec/02/oil-benefits-rural-uganda

Hardman Resources was quickly acquired by Tullow Oil, a London-based multinational oil and gas exploration company, for $1.1 billion, giving it full control of permit Block 2 (see map below).24https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/WPM-601.pdf

Between 2006 and 2008, more discoveries substantially increased the size of Uganda’s oil-yielding concessions and attracted a slate of international investors. By 2012, following further purchases and sales, as well as significant delays due to contract negotiations and tax disputes, the investment picture evolved into a tripartite international consortium under which the French supermajor oil company TotalEnergies, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), and Tullow each operated one of the three major permit Blocks, and each held a one-third stake in each of the Blocks.25https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/WPM-601.pdf This surge of discovery and investment in Ugandan hydrocarbons was mirrored across the sub-continent: between 2009 and 2014, as a result of increasing international interest and exploration in the region, Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for nearly 30% of global oil and gas discoveries.26https://www.icafrica.org/fileadmin/documents/Knowledge/Energy/AfricaEnergyOutlook-IEA.pdf

After further assessment and drilling, the Ugandan government estimated that there were around 6.5 billion barrels of oil under Lake Albert, of which between 1.8 and 2.2 billion barrels were judged to be recoverable.27https://energycapitalpower.com/play-by-play-albertine-graben/ Based on these discoveries, it was projected that oil production could be as much as 250,000 barrels per day, for as long as thirty years.28https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2014/02/25/local-communities-and-oil-discoveries-a-study-in-ugandas-albertine-graben-region/ If these estimates prove true, it would make Uganda the fifth-largest oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa, and create enormous revenue for the Ugandan government.29Vokes, R. (2012). BRIEFING: THE POLITICS OF OIL IN UGANDA. African Affairs, 111(443), 303–314. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41494490 At an estimated average of $38 per capita per year over a thirty-three-year period, this oil revenue by itself would not be a game-changer; but, when combined with the potential downstream effects – including increased infrastructure investment, foreign direct investment, employment opportunities, and capacity building – commercialization of the Albertine oil has the potential to transform Uganda’s largely agriculture-based economy.30Wolf, Sebastian, and Vishal Aditya Potluri, ‘Uganda’s Oil: How Much, When, and How Will It Be Governed?’, in John Page, and Finn Tarp (eds), Mining for Change: Natural Resources and Industry in Africa (Oxford, 2020; online edn, Oxford Academic, 19 Mar. 2020), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198851172.003.0014

Whether this transformation would more closely resemble the broad-based economic growth and development promised by the Ugandan government and the oil companies, or the increased conflicts, instability and underdevelopment associated with the well-documented “Oil Curse” (also called the “Resource Curse”), has been the subject of much debate.31https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/oil-discoveries-in-uganda-a-blessing-or-curse/ What has been clear from the beginning, however, is that in order to efficiently export the remote Albertine oil to international markets, the construction of a massive pipeline to the East African coast would be necessary.32https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/WPM-601.pdf

Since as early as 2011, plans for a regional pipeline to transport Ugandan oil for export have been in development.33https://jp.reuters.com/article/eastafrica-pipeline-idINLDE74A0GX20110511

Nevertheless, despite the size of the potential revenues from oil export, and the recognition of the necessity of a pipeline to realize those revenues, construction of such a pipeline has been subject to myriad difficulties and repeated delays. Even now, more than seventeen years after discovery, construction has yet to commence.34https://www.independent.co.ug/eacop-construction-starts-after-june-delayed-by-pap-grievances

The lack of progress can be largely attributed to a number of factors, including: the remote location of the oil reserves, which greatly increases the cost and difficulty of development and transportation; the dearth of supporting infrastructure; the long-term economic uncertainty over oil prices; and Uganda’s lack of access to sea or ocean, which makes all decisions about transporting the oil necessarily international and diplomatic in nature.35https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/WPM-601.pdf

Still, while these factors have certainly hampered progress, a significant part of the holdup must also be attributed to the Ugandan political context, the unpredictability of which has increased risk and engendered dispute and delay.36https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/WPM-601.pdf Uganda is a constitutional republic, whose most recent constitution provides for a directly-elected president (who is head of state, government, and the armed forces) and for a unicameral Parliament in which legislative power is vested, and whose members are, for the most part, directly elected.37https://www.britannica.com/place/Uganda/Government-and-society Nevertheless, despite holding regular, multi-party elections, the credibility of Uganda’s democracy has eroded over time, and the country has been ruled by the same party – the National Resistance Movement (NRM) – and the same president – Yoweri Museveni – since 1986.38https://freedomhouse.org/country/uganda/freedom-world/2021 Museveni and the NRM came to power after a five-year guerilla insurgency, and since then have retained political dominance through the manipulation of state resources, intimidation by security forces, and politicized prosecutions of opposition leaders.39https://freedomhouse.org/country/uganda/freedom-world/2021

Museveni – who was empowered by Parliament in 2012 to negotiate, grant and revoke oil licenses without parliamentary oversight – has driven a hard, and often unpredictable bargain, reversing his initial insistence on refining all crude oil in-country, delaying progress by engaging in numerous tax and regulatory disputes with international oil companies, and reneging on deals at the eleventh hour.40https://www.reuters.com/article/uganda-oil/ugandas-museveni-says-foreigners-sabotaging-oil-sector-idUSL5E8NDC5P20121213 https://www.reuters.com/article/uganda-oil-idAFL6N0WW4NE20150331 https://academic.oup.com/book/40396/chapter/347210146 Still, despite the uncertain regulatory environment and its associated risks, big oil has not given up on Uganda; sunk-costs and the prospects of future revenues have kept them playing ball.41https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/WPM-601.pdf

Oil companies, however, are by no means the only stakeholders which have had to weigh the costs and benefits of Ugandan oil production. The Ugandan people themselves (and their regional neighbors) have also spent the last decade and a half trying to sift through the various promises and predictions about what this oil means for them. On the one hand, there are the assurances put forth by Museveni and the oil industry that oil wealth will create new jobs, lift millions out of poverty, bring about technology transfer, bolster infrastructure, and – in short – raise Uganda into a middle-income country.42https://www.wjtv.com/news/international/report-east-africa-pipeline-breaches-banking-principles/ https://eacop.com/unlocking-east-africas-potential/#; https://eacop.com/faqs/

On the other hand are the warnings of activists, political scientists, and local communities that oil production will not only harm the environment and lead to massive carbon emissions, but that it could also prove to be a socio-economic scourge for Ugandans. In particular, many point to the Oil Curse, the well-documented – and perhaps counter-intuitive – social science finding that, on average, countries with natural resource wealth (especially oil) have failed to produce better economic outcomes than those without.43https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/cid/publications/faculty-working-papers/natural-resource-curse Indeed, countries that make new and sizable oil, gas, or mineral discoveries tend to experience higher rates of conflict and authoritarianism, and lower rates of economic stability and growth than their natural-resource-poor neighbors.44https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/nrgi_Resource-Curse.pdf The reasons for this phenomenon are widely debated, but likely include the fact that natural resource wealth – more than renewable sources of wealth – decreases government responsiveness by decreasing reliance on a citizen tax base, provokes and sustains internal conflicts as different groups fight for control of the resources, and harms other sectors of the economy through inflation or by shifting capital and labor.45https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/nrgi_Resource-Curse.pdf

Of course, not all countries are equally vulnerable to the negative effects of the resource curse. Factors such as institutional strength, social and economic stability, level of democratization, and prevalence of corruption all affect the extent to which a major discovery of natural resources are likely to be a blessing or a curse for any given nation.46Mehmet Efe Biresselioglu, Muhittin Hakan Demir, Arsen Gonca, Onat Kolcu, Ahmet Yetim, How vulnerable are countries to resource curse?: A multidimensional assessment, Energy Research & Social Science, Volume 47, 2019, Pages 93-101, ISSN 2214-6296, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.08.015 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629618301786 Unfortunately for Uganda, these and other indicators suggest that it is particularly susceptible to the potential pitfalls of newfound resource wealth. For example, although the country is nominally a democracy, it has been ranked very poorly by watchdogs on the strength of its institutions, the fairness of its elections, the freedom of its press, and the independence of its judiciary.47https://freedomhouse.org/country/uganda/freedom-world/2021 Furthermore, the country is plagued with high-level and pervasive corruption, a history of social and political conflict, a weak economy, and increased warnings by domestic civil society organizations about the likelihood of worsening political violence.48https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/uganda; https://www.africanews.com/2023/04/18/uganda-charges-second-minister-in-major-corruption-scandal/ https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/uganda/overview https://www.cfr.org/blog/keeping-eye-ugandas-stability It is no wonder, then, that many Ugandans fear that their Albertine oil could result in increased corruption, instability, poverty, and conflict.49https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/oil-discoveries-in-uganda-a-blessing-or-curse/

Still, this is the path that Museveni has decided to follow: “There is a lot of nonsense that the oil will be a curse,” he said, dismissing critics in 2006. “No way! The oil of Uganda cannot be a curse. Oil becomes a curse when you have got useless leaders, and I can assure you that we don’t approach that description even by a thousandth of a mile. … The oil is a blessing for Uganda and money from it will be used for development.”50Mbabazi, Pamela. The Oil Industry in Uganda; a Blessing in Disguise or an All Too Familiar Curse? The 2012 Claude Ake Memorial Lecture. 2013. http://nai.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:665238/FULLTEXT01.pdf

So, despite widespread concerns about the potential harms, Uganda’s government remained committed to extracting and exporting the country’s oil. And, in 2014, a deal seemed to have been reached that would allow them to do so: the Uganda-Kenya crude oil pipeline (UKCOP).51https://www.gem.wiki/Uganda–Kenya_Crude_Oil_Pipeline_(UKCOP) The planned pipeline was intended to not only transport the Ugandan oil, but also commercialize Kenyan oilfields along the route, and seemed to have the benefit of potential cost-sharing for infrastructure, as well as a history of common cross-border projects.52Brendon J. Cannon, Stephen Mogaka, Rivalry in East Africa: The case of the Uganda-Kenya crude oil pipeline and the East Africa crude oil pipeline, The Extractive Industries and Society, Volume 11, 2022, 101102, ISSN 2214-790X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2022.101102. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214790X22000636) Nevertheless, regional rivalries, Kenyan security challenges, effective lobbying from Tanzania, and TotalEnergies’ preference for a Tanzanian route led to Museveni jettisoning the project and instead announcing in 2016 the construction of a pipeline that would pass through Tanzania instead of Kenya – the East African Crude Oil Pipeline.53Brendon J. Cannon, Stephen Mogaka, Rivalry in East Africa: The case of the Uganda-Kenya crude oil pipeline and the East Africa crude oil pipeline, The Extractive Industries and Society, Volume 11, 2022, 101102, ISSN 2214-790X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2022.101102. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214790X22000636)

According to construction plans, EACOP will be a buried thermally-insulated 24″ pipeline intended to carry crude oil from the Lake Albert oil fields in Uganda to the Tanzanian coast on the Indian Ocean.54https://eacop.com/ It is being constructed in parallel with two upstream development projects, which, though not officially part of EACOP, share the same major financial backers as EACOP.55https://eacop.com/overview/

The first is the Tilenga project, which consists of 6 oil fields, and will include over 400 wells, oil and gas flow-lines, and a Central Processing Facility (CPF) to separate and treat the oil, water, and gas produced by the wells.56https://www.upstreamonline.com/field-development/tilenga-kingfisher-huge-contracts-near-as-uganda-and-tanzania-agree-key-oil-deals/2-1-993890 It is located on Block 2 (see Discovery section, above) on the northeast shore of Lake Albert, in the Buliisa and Nwoya districts, and is operated by TotalEnergies.57https://totalenergies.com/projects/oil/tilenga-and-eacop-acting-transparently It is expected to produce around 204,000 barrels per day (bpd).58https://eacop.com/overview/

The second, and smaller, upstream project is named Kingfisher and consists of a single oil field, with plans for 31 wells, 19 kilometers of flowlines, a CPF, and other facilities. It is located on Block 3A (south of the Tilenga project) on the long southeastern shore of the lake, in the Kikuube district. It is operated by CNOOC and is expected to produce 40,000 bpd.59https://pau.go.ug/the-kingfisher-development-project/

Both projects are jointly owned by TotalEnergies (56.67% stake), CNOOC (28.33%) and UNOC (15%).60https://www.upstreamonline.com/field-development/tilenga-kingfisher-huge-contracts-near-as-uganda-and-tanzania-agree-key-oil-deals/2-1-993890 Together, they are expected to cost around $16 billion, according to Ugandan officials.61https://www.upstreamonline.com/field-development/tilenga-kingfisher-huge-contracts-near-as-uganda-and-tanzania-agree-key-oil-deals/2-1-993890

Once processed at the Tilenga and Kingfisher CPFs, the oil produced at these upstream projects will be transported by feeder lines to Kabaale, a town in Hoima district, and the starting point of the pipeline. There, at the Kabaale Industrial Park (currently under construction), the oil will be metered and then combined into a single stream, with the Ugandan Oil Refinery having the right to the first 60,000 bpd to serve domestic and regional markets, and the remainder – some 184,000 bpd – being channeled into EACOP.62https://pau.go.ug/the-uganda-refinery-project/ https://eacop.com/overview/ The pipeline will then transport the oil over 1,443 kilometers (897 miles) to the Chongoleani peninsula, just north of the Port of Tanga on the Tanzanian coast, where it will be exported to international markets.63https://eacop.com/ The route – 80% of which is in Tanzania – heads south 296 kilometers from Kabaale through Uganda to the Tanzanian border and tracks the western shore of Lake Victoria, before turning east and cutting through the heart of Tanzania’s northern savannahs and steppes toward the ocean.64https://eacop.com/route-description-map/

Under current agreements, the pipeline would be operated through a dedicated Pipeline Company (also called EACOP), and the shareholders in EACOP would be the three upstream project partners – TotalEnergies (62%), UNOC (15%), and CNOOC (8%) – along with TPDC (15%).65https://www.ogj.com/pipelines-transportation/pipelines/article/14288579/uganda-approves-eacop-construction-to-start-late-2023 (TotalEnergies acquired Tullow’s entire interests in 2020).66https://totalenergies.com/media/news/news/total-acquires-tullow-entire-interests-uganda-lake-albert-project Despite the financial heft and commitment of its partners, however, EACOP is no done deal. While construction of the upstream plants has begun in earnest, and the pipeline’s ground-breaking is eternally imminent, the project’s backers have struggled to secure international financing. The reason? The project is a potential catastrophe for both people and the planet.

When oil was discovered in 2006, some residents of the lakeside Hoima district received the news with optimism that oil production would bring them the jobs and money necessary to lift them out of poverty.67https://observer.ug/business/38-business/38987-oil-rich-hoima-struggles-to-solve-the-land-question Even now many local residents say they remain unafraid of the project’s potential risks, and are excited about its potential benefits.68https://redpepper.co.ug/excitement-as-eacop-affected-persons-get-new-houses/128666/ Others, however, have found themselves homeless or internally displaced, evicted from their customary lands with little compensation.69https://observer.ug/business/38-business/38987-oil-rich-hoima-struggles-to-solve-the-land-question

Indeed, the most immediate effects of EACOP and its associated projects will likely be on the thousands of people who live along the proposed pipeline route and upstream construction sites. The Ugandan section of the pipeline will cut through 10 districts, 25 sub-counties and 178 villages in Uganda, while the Tanzanian section will traverse an additional 8 regions, 25 districts and 231 villages.70https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621045/rr-empty-promises-down-line-101020-en.pdf Many of these communities are dependent on crop agriculture, livestock rearing, hunting, fishing and forestry, and so are extremely vulnerable to the loss of land that will result from EACOP.71https://www.brookings.edu/articles/local-communities-and-oil-discoveries-a-study-in-ugandas-albertine-graben-region/ For although the proposed pipeline is only 2 feet wide, and will be buried at a depth of around 2 meters along most of its route, its impact on the land will nevertheless be substantial.72https://e360.yale.edu/features/a-major-oil-pipeline-project-strikes-deep-at-the-heart-of-africa To undertake construction, the pipeline will require, at a minimum, a 30 meter wide “right of way” along its entire length.73https://eacop.com/faqs/ This massive corridor of land, two thirds of cuts through farmland, will be kept clear of buildings, trees, and crops in order to accommodate the more than 80 control stations that will pump, heat, and pressurize the oil along the route.74https://www.stopcambo.org.uk/updates/stopeacop https://e360.yale.edu/features/a-major-oil-pipeline-project-strikes-deep-at-the-heart-of-africa Many of the people who live in and around the affected villages will therefore lose the land upon which they depend for their livelihoods. Others will have to be permanently relocated.

For Tilenga and EACOP, TotalEnergies has claimed that these projects will require the relocation of 764 primary residences, and “will affect a total of 18,800 stakeholders, landowners and land users.”75https://totalenergies.com/projects/oil/tilenga-and-eacop-acting-transparently Watchdog groups, however, argue that this is a vast undercount. For example, according to one estimate, roughly 13,000 households, accounting for more than 86,000 people, have lost or will lose land as a result of the pipeline.76https://www.amisdelaterre.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/20210407-numbers-of-individual-persons-affected-by-eacop.pdf According to the same estimate, an additional 4,865 households, accounting for 31,716 people, are directly affected by the Tilenga project and 680 households, or roughly 2,949 people, will be affected by the Kingfisher project. In total, perhaps as many as 120,000 individuals will be directly impacted by EACOP and its associated project – more than five times the official estimate.77https://www.amisdelaterre.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/20210407-numbers-of-individual-persons-affected-by-eacop.pdf

The project’s backers have promised that those who require their primary dwelling to be relocated will be “offered replacement houses of a higher standard than their existing dwelling.”78https://eacop.com/faqs/ Others affected by the project, the pipeline company has promised, will be offered cash compensation, as well as “in-kind compensation including transitional food support, financial literacy training and access to livelihood restoration programs.”79https://eacop.com/faqs/ However, these commitments have reportedly already been broken in many cases. Several reports, including one from the Uganda Land Alliance, indicate that oil exploration activities in the region have already led to changes in land ownership, as well as increased conflict and displacement.80https://www.brookings.edu/articles/local-communities-and-oil-discoveries-a-study-in-ugandas-albertine-graben-region/ In Hoima district, for example, more than 200 families have been evicted from their lands to pave the way for an oil-waste treatment plant.81https://observer.ug/business/38-business/38987-oil-rich-hoima-struggles-to-solve-the-land-question

One of the problems is that in much of rural Uganda, there are few official records of land ownership as many families have customary ownership.82Ashukem, J. N. (2020). Land Grabbing and Customary Land Rights in Uganda: A Critical Reflection of the Constitutional and Legislative Right to Land. International Journal on Minority and Group Rights, 27(1), 121-147. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718115-02701003 For instance, in 2005, before the discovery of oil, Hoima district received only 14 applications for land registration. Following the discovery of oil, however, this number exploded to 1,235, with many residents soon discovering that their customary lands had been officially registered out of their control.83https://observer.ug/business/38-business/38987-oil-rich-hoima-struggles-to-solve-the-land-question

This sort of uncompensated forced relocation is just one of the many potential human rights violations associated with large-scale infrastructure projects. Indeed, as documented by UNHCR, “mega-infrastructure investments” have a long history causing or leading to serious human rights violations, such as: 84https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/Baseline-Study-on-the-Human-Rights-Impacts-and-Implications-of-Mega-Infrastructure-Investment.pdf (pg. 5-7)

In response to concerns that EACOP could repeat many of the human rights violations typical of large-scale infrastructure projects, EACOP’s backers have released a human rights policy that makes commitments with regards to many of the specific rights at issue, as well as the more general claim that “EACOP commits in all our activities to … respect human rights in carrying out our business activities.”85https://eacop.com/human-rights-policy/

The risks associated with EACOP extend even beyond those to the people living and working directly in its path. EACOP, and its associated upstream projects, also pose an enormous risk to the planet – in particular to nature, wildlife, and the climate.

Nature and Wildlife

According to analyses of the pipeline’s route, EACOP passes through one of the most ecologically diverse and wildlife-rich regions of the world.86https://e360.yale.edu/features/a-major-oil-pipeline-project-strikes-deep-at-the-heart-of-africa Over its 1,443 kilometer length, the pipeline would traverse two major biodiversity hotspots, seven globally important ecoregions, and at least sixteen protected areas, many of which are classified as Key Biodiversity Areas.87https://mapforenvironment.org/story/The-East-African-Crude-Oil-Pipeline-EACOP-a-spatial-risk-perspective/111 Nearly 2,000 square kilometers of protected wildlife habitats would be significantly impacted, including the Taala Forest Reserve and Bugoma Forest in Uganda, and Biharamulo Game Reserve and Wembere Steppe Key Biodiversity Area in Tanzania.88https://media.wwf.no/assets/attachments/99-safeguarding_nature_and_people___oil_and_gas_pipeline_factsheet.pdf One of TotalEnergies’ Tilenga oil fields is even located inside Murchison Falls National Park, widely considered one of Uganda’s most beautiful National Parks.89https://totalenergies.com/projects/oil/tilenga-and-eacop-acting-transparently https://www.touropia.com/national-parks-in-uganda/

Together, these habitats are home to many endangered species such as the Eastern Chimpanzee and African Elephant, as well as lions, elands, lesser kudu, buffalo, impalas, hippos, giraffes, roan antelopes, sitatungas, sables, zebras, aardvarks, and monkeys, all of which will be at risk of significant habitat disturbance, fragmentation, and increased poaching due to the pipeline’s construction and operation.90https://www.stopeacop.net/for-nature The American environmentalist Bill McKibben sharply criticized the project, writing that “the proposed route looks almost as if it were drawn to endanger as many animals as possible.”91https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-a-warming-planet/with-a-new-pipeline-in-east-africa-an-oil-company-flouts-frances-leadership-on-climate And, by cutting through such an ecologically rich region, the project also has the potential to bring about heavy deforestation, which is particularly problematic considering that, according to Global Forest Watch, Uganda is already losing an average of over 75,000 hectares of tree cover and almost 4,000 hectares of primary forest each year.92https://mapforenvironment.org/story/The-East-African-Crude-Oil-Pipeline-EACOP-a-spatial-risk-perspective/111

For over 400 kilometers, the pipeline would also run alongside Lake Victoria, the largest lake in Africa and the second-largest fresh water lake in the world.93https://www.britannica.com/place/Lake-Victoria The Lake Victoria basin – which supports the livelihoods of more than 30 million people in the region – would be at high risk of pollution and degradation from oil spillage and other infrastructure-related effects.94https://media.wwf.no/assets/attachments/99-safeguarding_nature_and_people___oil_and_gas_pipeline_factsheet.pdf And, to make matters worse, the proposed route passes through a seismically active region, crosses an estimated 230 rivers through open trenches, and terminates at a coastline where tankers up to 300 meters long will be filled while floating next to two large Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) rich with mangroves and coral reefs, and home to dugongs, dolphins, and sea turtles.95https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/14/world/africa/oil-pipeline-uganda-tanzania.html; https://e360.yale.edu/features/a-major-oil-pipeline-project-strikes-deep-at-the-heart-of-africa In response to these and other concerns, EACOP’s backers have produced numerous Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (ESIAs).96https://eacop.com/esia-report-uganda/ Nevertheless, the assessments for EACOP and its upstream projects have been heavily criticized by independent experts as insufficient, including (but not only) because of their failure to include a robust oil spill emergency response plan.97https://www.amisdelaterre.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/08-december-19-e-tech-evaluation-of-total-tilenga-esia.pdf; Netherlands Commission for Environmental Assessment, “Advisory Review of the ESIA for the East African Crude Oil Pipeline,” June 2019; https://www.inclusivedevelopment.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/EACOP-EPs-assessment.pdf

Climate Change Consequences

Beyond these potentially devastating environmental risks to the people, environment, and wildlife of Uganda and Tanzania, the EACOP project, if completed, is likely to also have significant warming impacts for the entire planet. Both Uganda and Tanzania are signatories of the Paris Agreement, which commits parties to the goal of limiting “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursuing efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.”98https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2016/04/parisagreementsingatures/

According to an analysis by the Climate Accountability Institute (CAI), the EACOP project would produce around 379 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions over 25 years, with peak annual emissions more than doubling the current annual emissions of Uganda and Tanzania combined.99https://climateaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/CAI-EACOP-Rptlores-Oct22.pdf This total accounts for the full value chain of emissions from the transportation of crude oil through the pipeline to the oil’s end use by consumers around the world.100The CAI total does not include oil field operation, which includes “emissions from natural gas production or gas used in power generation, or flaring.“ At the Kingfisher oil fields, CNOOC has affirmed that “natural gas produced will be consumed in combustion processes,” and that “56% will be used for power generation (16 MW output), the remainder (44%) flared.” As such, the additional emissions from associated natural gas – which is estimated to be produced at 3.34 billion cubic feet per year – could be substantial. A parallel assessment from Total concerning emissions from producing oil and gas at the Tilenga fields could not be found. https://climateaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/CAI-EACOP-Rptlores-Oct22.pdf

The environmental assessments presented by the EACOP consortium, on the other hand, only considered the impacts of the construction and operation of the pipeline, neglecting over 98% of the project’s total emissions, including emissions from maritime transport of the crude oil to global markets, from its refinement into petroleum products, and, more significantly, from the end use of the oil by consumers.101https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/oct/27/east-african-crude-oil-pipeline-carbon

Based on the more realistic estimates of EACOP’s potential emissions, some experts have characterized the project as a “mid-sized climate bomb.”102https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/oct/27/east-african-crude-oil-pipeline-carbon Nevertheless, the climate impact of EACOP may yet be understated. This is because the extension of big oil’s reach into East Africa is unlikely to terminate in Uganda, and the pipeline could facilitate the export of even more remote oil from Central and Eastern Africa. Analyses have shown that the pipeline could be used to export oil from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, and South Sudan, as well as other oil fields in Uganda, thereby extending its lifespan and increasing the emissions it will enable.103https://www.banktrack.org/article/financial_and_reputational_risks_of_eacop_pile_up_amidst_growing_opposition_to_project

DRC, for example, recently announced that it was in discussions with Uganda for possible use of EACOP to export its own Albertine oil reserves (the Albertine Graben is on the border of the two nations).104https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/congo-discussions-with-uganda-over-use-crude-pipeline-2023-05-10/ In preparation, the DRC has begun auctioning the rights for 30 oil and gas blocks near the Ugandan border.105https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/congo-oil-blocks-auction-draws-warnings-environmental-catastrophe-2022-07-28/ The blocks cover more than 11 million hectares of tropical forest – an area nearly the size of England – paving the way for drilling within the Congo Rainforest (the world’s second largest, after the Amazon), a huge swath of carbon-dense peatlands, and Virunga National Park, a sanctuary for endangered mountain gorillas.106https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/congo-oil-blocks-auction-draws-warnings-environmental-catastrophe-2022-07-28/ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/10/dash-african-gas-wipe-out-congo-basin-rainforests Present at the launch of bidding in Kinshasa were representatives from TotalEnergies (though they ultimately did not bid).107https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/congo-oil-blocks-auction-draws-warnings-environmental-catastrophe-2022-07-28/

With or without EACOP, the rush for fossil fuel extraction in Africa is well underway, with almost 10% of the African continent already covered by oil and gas production fields.108https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/10/dash-african-gas-wipe-out-congo-basin-rainforests An additional 28%, however, is under threat under current project proposals, including 64 million hectares of dense forest in the Congo basin.109https://www.rainforestfoundationuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Congo-in-the-Crosshairs-Report-EN.pdf The impact of exploration there would not only be catastrophic for the climate, but also for 35 million people, including hundreds of thousands of Indigenous people, who live in designated or proposed oil and gas fields.110https://www.rainforestfoundationuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Congo-in-the-Crosshairs-Report-EN.pdf If completed, then, EACOP may prove to be the 1,443km fuse that ignites the immense carbon and human rights bomb that is the Congo basin’s untapped oil.111https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2022/07/27/an-oil-auction-in-congo-bodes-ill-for-the-climate

Considering the breadth and magnitude of EACOP’s potential harms, it should come as no surprise that the opposition to the project is commensurately broad and intense. For more than a decade, local residents, environmental activists, student organizers, human rights defenders, and independent journalists in Uganda and Tanzania have been speaking out against EACOP.112https://wagingnonviolence.org/2022/06/climate-activists-global-south-north-unite-stop-east-africa-crude-oil-pipeline/ Thousands have peacefully protested against the pipeline’s environmental and human costs and many in Uganda have been threatened or arrested for doing so (even though the right to peaceably assemble is protected by the Ugandan constitution).113https://seasonofcreation.org/2020/09/21/eacop-and-the-dangers-of-speaking-out-against-it-in-uganda/ https://www.reuters.com/article/uganda-oil-protests/feature-they-want-to-silence-us-uganda-cracks-down-on-anti-oil-protests-idUSL8N33V2LT https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/44038/90491/F206329993/UGA44038.pdf

In addition to this longstanding domestic and local resistance, EACOP’s potential climate impact has also spurred growing international attention and opposition.114https://www.democracynow.org/2022/11/16/activists_mobilize_stop_construction_east_african Major international climate and human rights organizations have, in concert with local groups, implemented campaigns to document and publicize EACOP’S potential harms and pressure governments, companies, and financial institutions to oppose the project.115https://www.law.georgetown.edu/environmental-law-review/blog/the-east-african-crude-oil-pipeline-why-are-some-east-africans-opposed/

A major player in this movement is #StopEACOP, a coalition of over 260 civil society organizations, more than 100 of which are based in Africa.116https://www.stopeacop.net/our-coalition Members of the coalition include:

#StopEACOP is focused on a campaign to publicize the potential costs of EACOP to people, nature, and the climate. In doing so, the coalition hopes to encourage people around the world to “support the communities on the frontlines” and put pressure on international investors, banks, and insurance firms to “make sure EACOP is starved of the corporate and political support it needs.”117https://www.stopeacop.net/home These latter efforts have been particularly successful, with at least 27 banks and 22 large insurers ruling out financial or insurance support to the pipeline project.118https://www.stopeacop.net/banks-checklist https://www.stopeacop.net/insurers-checklist

Ugandan authorities in 2021 suspended the operations of 54 NGOs, including some of those involved in StopEACOP.119https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/uganda-suspends-work-54-ngos-increasing-pressure-charities-2021-08-20/ The government cited a range of reasons, including non-compliance with regulations, but human rights groups and the organizations affected have said that the suspensions were, in reality, part of a concerted effort to crackdown on civil society and – in particular – undermine opposition to oil development.120https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/08/27/uganda-harassment-civil-society-groups Since then, the Ugandan High Court has overturned the suspension of at least one of the NGOs – Chapter Four Uganda, a legal aid organization – but activists note that the atmosphere of fear and uncertainty remains.121https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/05/24/court-ends-suspension-ngo-uganda

Other groups have gone beyond public pressure campaigns and have mounted legal challenges to the pipeline and its financing. In 2019, for example, six French and African civil society organizations, led by Les Amis de la Terre France, filed a lawsuit in France against TotalEnergies (which is headquartered in the Paris suburbs) for allegedly failing to comply with France’s due diligence law.122https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/gallery/2023/feb/24/counting-the-cost-of-ugandas-east-africa-oil-pipeline The 2017 Duty of Vigilance law requires French companies with more than 10,000 employees to establish and implement “reasonable vigilance measures adequate to identify risks and to prevent severe impacts on human rights and fundamental freedoms, on the health and safety of individuals and on the environment.”123https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/total-lawsuit-re-failure-to-respect-french-duty-of-vigilance-law-in-operations-in-uganda/ The lawsuit sought a judicial order to halt the EACOP project under a special fast-track process, but was dismissed on procedural grounds.124https://www.law.com/international-edition/2023/03/03/closely-watched-climate-change-case-in-france-falters-on-procedural-grounds/ https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/totalenergies-faces-second-lawsuit-over-uganda-oil-projects-2023-06-27/ The judge found that TotalEnergies’ “vigilance plan” was legally adequate, so a fast-track process was not appropriate.125https://www.offshore-technology.com/news/totalenergies-in-court-again-over-operations-in-east-africa/ Nevertheless, the judgement rejected TotalEnergies’ argument that the French Government has no jurisdiction over the company’s activities in foreign countries, and added that a detailed investigation in a standard-speed trial could examine whether the company’s actions conformed to their vigilance plan.126https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/totalenergies-faces-second-lawsuit-over-uganda-oil-projects-2023-06-27/ https://www.offshore-technology.com/news/totalenergies-in-court-again-over-operations-in-east-africa

In response, the same coalition of activist groups filed a second case in June, 2023, this time with 26 Ugandan plaintiffs who say they have suffered “serious harm,” especially to their rights to land and food.127https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20230627-ugandans-sue-totalenergies-in-france-for-reparations-over-human-rights-violations Rather than seeking an order to halt construction, the new lawsuit instead seeks reparations for harms which have already occurred.128https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/france-communities-and-ngos-use-duty-of-vigilance-law-to-sue-totalenergies-over-alleged-human-rights-abuses-over-giant-oil-project-in-uganda/

Additionally, in 2021 three organizations filed a complaint against the World Bank for indirectly backing EACOP and the Kibaale refinery, arguing that the International Finance Corporation (IFC), part of the World Bank Group, has helped to enable the project through its investment in a pan-African insurer which has said that it will provide insurance coverage for EACOP and the refinery.129https://www.inclusivedevelopment.net/pipelines/world-banks-back-door-support-for-east-african-oil-pipeline-imperils-the-planet-complaint-alleges/

Similarly, several human rights and environmental groups, including 10 Ugandan and Tanzanian organizations and Inclusive Development International, have brought a complaint to the U.S. government against New-York-based insurance broker firm Marsh in relation to its reported role as insurance broker for the construction phase of EACOP.130https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/14/world/africa/oil-pipeline-uganda-tanzania.html https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2022-05-19/insurance-giant-marsh-signs-on-for-environmentally-disastrous-pipeline-project In particular, the lawsuit accuses Marsh of violating the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises with regard to respect for human rights and the environment by supporting a project that the complainants claim is “expected to cause – and in many instances, is already causing – extensive and severe adverse human rights and environmental impacts.”131https://www.inclusivedevelopment.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Marsh-NCP-Complaint-Summary-and-Key-Points-FINAL.pdf https://www.lemonde.fr/en/le-monde-africa/article/2023/02/08/uganda-s-eacop-pipeline-insurer-marsh-targeted-by-complaint-filed-with-oecd_6014929_124.html

There have also been legal challenges to the pipeline within East Africa. For instance, in 2020, a coalition of NGOs – including Natural Justice, the Centre for Strategic Litigation, the Centre for Food and Adequate Living Rights (CEFROHT), and the Africa Institute for Energy Governance (AFIEGO) – filed a case against the governments of Uganda and Tanzania in the East African Court of Justice, challenging the construction of EACOP on the grounds that it would be in violation of numerous international and regional treaties.132https://naturaljustice.org/eacop-east-african-court-of-justice-will-hear-arguments-on-courts-jurisdiction/ In particular, they argue that the project will lead to the displacement of thousands of villagers, cause environmental destruction, and contribute significant carbon emissions.133https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/ngos-petition-regional-court-to-stop-construction-of-east-african-crude-oil-pipeline-citing-social-environmental-concerns/ The case is pending.

A number of organizations have also focused on conducting human rights and environmental assessments of EACOP and its associated projects, including harms that have already occurred in the planning and preparatory stages of the project. Oxfam, for example, conducted a “Human Rights Impact Assessment” in 2020 and found that the construction and operation of EACOP is “likely to affect [the] human rights of the communities where the project is situated” and is already creating “significant new risk and uncertainty for those people who currently depend on the land for farming, grazing, forestry, or fishing.”134https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621045/rr-empty-promises-down-line-101020-en.pdf For instance, they argue that thousands of household in Tanzania and Uganda will lose their land, and document how the land acquisition process has already been “marked by confusion, shortcomings in assessment and valuation processes, delayed compensation and lack of transparency.”135https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621045/rr-empty-promises-down-line-101020-en.pdf In addition, the report argues that the EACOP project is likely to have a disproportionate effect on women – a finding that TotalEnergies acknowledges to be true.136https://totalenergies.com/sites/g/files/nytnzq121/files/documents/2021-03/EACOP_Oxfam_Report_Total_Reco-Action_Plan_2021_02.pdf Indeed, Oxfam found that there have already been increases in levels of gender-based violence, and that many communities fear that high-risk sexual behaviors and commercial sex work will increase along the pipeline’s corridor, likely contributing to ongoing public health crises.137https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621045/rr-empty-promises-down-line-101020-en.pdf

The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) has also conducted an impact assessment of the project, and found that:138https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/fidh__fhri_report_uganda_oil_extraction-compresse.pdf

“Delays in compensation and relocation due to the project’s suspension continue to threaten the livelihoods of communities, and have considerably limited their use of land; inadequate compensation rates are unable to provide sufficient means for them to restore or sustain their standard of living; and the increasing pressure on natural resources and the reduction in available nearby land further limit their capacity for resilience, in an area where the effects of the climate crisis are already translating into longer periods of drought and reduced harvests.”

The 2020 report finds fault not only with the inadequate and culturally-insensitive actions of the companies involved, but also with the state of Uganda, which FIDH claims has failed in its obligations to guarantee the rights to land, an adequate standard of living, and prior, prompt, and adequate compensation.139https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/fidh__fhri_report_uganda_oil_extraction-compresse.pdf

A 2023 Human Rights Watch report confirms the worst fears of these previous assessments. After conducting interviews with 75 displaced families in five districts of Uganda, the international human rights NGO reports that there have been “devastating impacts on livelihoods of Ugandan families from the land acquisition process.”140https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/07/10/our-trust-broken/loss-land-and-livelihoods-oil-development-uganda In particular, Human Rights Watch found that:141https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/07/10/our-trust-broken/loss-land-and-livelihoods-oil-development-uganda

“The land acquisition process has been marred by delays, poor communication, and inadequate compensation. … [A]ffected households are much worse off than before. Many interviewees expressed anger that they are still awaiting the adequate compensation promised by TotalEnergies and its subsidiaries in early meetings in which company representatives extolled the virtues of the oil development. Families described pressure and intimidation by officials from TotalEnergies EP Uganda and its subcontractors to agree to low levels of compensation that was inadequate to buy replacement land. Most of the farmers interviewed from the EACOP pipeline corridor, many of them illiterate, said that they were not aware of the terms of the agreements they signed. Those who have refused signing described facing constant pressure from company officials, threats of court action, and harassment from local government and security officials.”

In response to the claims and actions of the multitude of opposition groups, the project’s backers have repeatedly rejected reports of human rights harms and denied any wrongdoing.142https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/french-court-rejects-lawsuit-brought-against-totalenergies-uganda-pipeline-2023-02-28/ In response to the Human Rights Watch report, for instance, TotalEnergies wrote that the “EACOP projects continue to pay close attention to the respect of the rights of the communities concerned,” and that compensation paid has met the standard of “full replacement value.” The backers have further pledged to protect human rights and adhere to international Environmental and Social requirements, specifically the Equator Principles and the IFC Performance Standards.143https://eacop.com/environment-biodiversity/

Within the region, however, the message from the governments and companies involved has focused less on avoidance of harms and more on the potential benefits of EACOP, including increased foreign direct investment, employment, and business opportunities, as well as the enhancement of the central trade corridor between Uganda and Tanzania. Museveni has promised that Uganda’s economy will grow between 9 and 10 percent once oil production begins, while his Tanzanian counterpart, President Samia Suluhu Hassan, has touted the jobs, infrastructure, and revenues she expects to result from the project.144https://allafrica.com/stories/202105121016.html http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/africa/2021-04/11/c_139873423.htm

According to reports, infrastructure around the Albertine oil fields is rapidly being built. The project’s backers have already spent an estimated $4 billion on construction and, according to TotalEnergies, compensation for land acquisition along the pipeline’s route has been paid for 93% of impacted households.145https://e360.yale.edu/features/a-major-oil-pipeline-project-strikes-deep-at-the-heart-of-africa https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/07/10/our-trust-broken/loss-land-and-livelihoods-oil-development-uganda As a result, some opponents of the pipeline fear that the project cannot be stopped.146According to conversation in which CRI has participated. Nevertheless, it appears that minimal progress has been made on the pipeline corridor to the ocean, leaving many with hope that “the battle is not over.”147https://lens.civicus.org/game-not-over-resistance-against-east-african-crude-oil-pipeline/

This hope has been bolstered by a number of recent international developments, including the European Parliament’s 2022 resolution denouncing the consequences of oil megaprojects in East Africa, particularly those involving TotalEnergies, including Tilenga and EACOP.148https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/RC-9-2022-0409_EN.html The non-binding resolution, which passed by a large majority, called for TotalEnergies to halt drilling in “protected and sensitive” ecosystems and postpone work on EACOP for a year to “study the feasibility of an alternative route,” citing “human rights violations,” “acts of intimidation,” “judicial harassment,” and “immense” risks to people, nature, and the climate.149https://www.lemonde.fr/en/le-monde-africa/article/2022/09/16/european-parliament-slams-two-totalenergies-oil-projects-in-uganda_5997139_124.html In response, TotalEnergies claimed that the resolution was based on “serious and unfounded allegations,” while Uganda’s deputy speaker called it “an affront to the independence” of a “sovereign country.”150https://totalenergies.com/media/news/press-releases/totalenergies-answer-european-parliament https://www.lemonde.fr/en/le-monde-africa/article/2022/09/16/uganda-furious-eu-parliament-called-to-postpone-oil-megaprojects_5997181_124.html Museveni dismissed the resolution’s importance, warning that if TotalEnergies wavered in their commitment to the project, “we shall find someone else to work with.” “Either way,” he promised, “we shall have our oil coming out by 2025 as planned.”151https://www.upstreamonline.com/energy-transition/-we-ll-find-someone-else-to-work-with-totalenergies-not-indispensable-to-oil-project-warns-museveni/2-1-1303425

Indeed, commercialization of the Lake Albert oil cleared one of its last major hurdles in early 2022 when the major stakeholders – Uganda, Tanzania, TotalEnergies, CNOOC, UNOC, and TPDC – reached a Final Investment Decision (FID) on the “Lake Albert Resources Development Project,” which encompasses both EACOP and the Tilenga and Kingfisher upstream projects.152https://jpt.spe.org/totalenergies-and-cnooc-announce-fid-for-10-billion-uganda-and-tanzania-project The FID signified a commitment by the participating parties to invest over $10 billion in the project, and was met with dismay by environmental activists and human rights defenders.153https://www.tanzaniainvest.com/energy/eacop-final-investment-decision Following the FID, Uganda officially launched its first oil drilling program, on CNOOC’s Kingfisher oil fields, with production expected to commence in 2025.

Nevertheless, in order to sell the oil they produce, Uganda will need a pipeline. And there remain obstacles to EACOP’s completion – namely, the consortium’s as yet unfulfilled need for a $3 billion project finance loan in order to proceed with construction, as well as access to adequate insurance.154https://www.banktrack.org/article/standard_chartered_refuses_financing_for_controversial_5_billion_ugandan_oil_pipeline Historically, receiving such financial support would not be a problem for a company like TotalEnergies, but as the result of the sustained international pressure campaign and organized local opposition, nine out of TotalEnergies’ 10 largest financiers have announced that they will not support the project.155https://www.banktrack.org/success/more_major_banks_and_insurers_refuse_to_support_eacop_lloyds_syndicates_silent_amid_human_rights_abuses Indeed, as of June 2023, almost 30 major international banks have ruled out financing EACOP, including JP Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Wells Fargo, HSBC, Credit Suisse, BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank, Barclays, Citi, and Santander.156https://www.stopeacop.net/banks-checklist Only South Africa’s Standard Bank, Japan’s Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) are currently financial advisors to the project – but they are expected to need another dozen (or more) banks to join them to secure the necessary $3 billion.157https://www.banktrack.org/blog/who_will_finance_the_east_african_crude_oil_pipeline Additionally, because of the continually increasing reputational, legal, and financial risks of the project, more than 20 of the world’s largest multinational commercial insurance companies have ruled out providing support to EACOP.158https://www.banktrack.org/article/financial_and_reputational_risks_of_eacop_pile_up_amidst_growing_opposition_to_project https://www.stopeacop.net/insurers-checklist

EACOP poses immense risks to human rights, the climate, and the environment. These risks, in turn, have proven to be a threat to the projects themselves, with community activists, international human rights and climate organizations, and people across the world speaking out against these projects and those who would enable them. As it stands, then, it is an open question whether EACOP will ever be built; whether billions of barrels of Albertine oil will reach global consumers; and whether the rights of people, the integrity of nature, and the future of the planet will be sacrificed for corporate greed and political expediency.